County magistrate

County magistrate (simplified Chinese: 县令; traditional Chinese: 縣令; pinyin: xiànlìng or simplified Chinese: 县长; traditional Chinese: 縣長; pinyin: xiànzhǎng) sometimes called local magistrate, in imperial China was the official in charge of the xian, or county, the lowest level of central government. The magistrate was the official who had face-to-face relations with the people and administered all aspects of government on behalf of the emperor. Because he was expected to rule in a disciplined but caring way and because the people were expected to obey, the county magistrate was informally known as the Fumu Guan (Chinese: 父母官; pinyin: fùmǔ guān), the "Father and Mother" or "parental" official.[1]

The emperor appointed magistrates from among those who passed the imperial examinations or had purchased equivalent degrees. Education in the Confucian Classics indoctrinated these officials with a shared ideology that helped to unify the empire, but not with practical training. A magistrate acquired specialized skills only after assuming office. Once in office, the magistrate was caught between the demands of his superiors and the needs and resistance of his often unruly constituents. Promotion depended on the magistrate's ability to maintain peace and lawful order as he supervised tax collection, roads, water control, and the census; handled legal functions as both prosecutor and judge; arranged relief for the poor or afflicted; carried out rituals; encouraged education and schools; and performed any further task the emperor chose to assign. Allowed to serve in any one place for only three years, he was also at the mercy of the local elites for knowledge of the local scene. There was a temptation to postpone difficult problems to the succeeding magistrate's term or to push them into a neighboring magistrate's jurisdiction. The Yongzheng emperor praised the magistrate: "The integrity of one man involves the peace or unhappiness of a myriad." [2] But a recent historian said of the magistrate that "if he had possessed the qualifications for carrying out all his duties, he would have been a genius. Instead, he was an all-around blunderer, a harassed Jack-of-all trades...." [3]

The Republic of China (1912 – ) made extensive reforms in county government, but the position of magistrate was retained. .[4] Under the People's Republic of China (1949 – ) the office of county magistrate, sometimes translated as "mayor," was no longer the lowest level of the central government, which extended its control directly to the village level.[5]

Terms

From ancient times until the end of the Tang dynasty in the eighth century, the office was called traditional Chinese: 縣令; simplified Chinese: 县令; pinyin: xiànlìng. In the following dynasties, the office was called Zhixian (知縣; 知县; zhīxiàn) until 1928, when the title was changed to 縣長; 县长; xiànzhǎng. [5]

History and changing functions

The county (xian) was established as the basic unit of local government around the year 690 B.C.E., during the Warring States period marked by competition between small-scale states. The Qin empire unified much of China in 221 BCE. and established the jun-xian Chinese: 郡县; pinyin: jùnxiàn (prefecture/ county) system, which divided the realm into jun (prefectures or commanderies) and xian (counties). Local administrators appointed by the central government replaced the leaders of feudal cities. In spite of many changes, the xian remained the basic unit of local government until the 20th century.[6]

Before the Qin unification in 221 BCE, local officials inherited office, which strengthened great families against the central government. After that unification, no official except the emperor was allowed to inherit or bequeath office. The control of local government then became a contest between the central bureaucracy, which represented the interests of the emperor, and local nobility and elites. Imperial power undercut the local aristocracy by appointing scholar officials chosen by merit through the examination system who were not necessarily of noble descent. The Han dynasty regularized the position, and initiated the "rule of avoidance", which forbade a magistrate to serve in his home county because of the danger of nepotism and favoritism to family or friends.[7] After the Sui dynasty in the sixth century, the rule of avoidance was strictly enforced; in later dynasties a magistrate could serve only up to four years in any one place before being transferred.[2]

The magistrate was supervised by the prefect (zhifu) or the equivalent, who in turn was ordinarily under the circuit intendant (dao), or perhaps a circuit intendant with such special responsibilities as waterworks, grain, or salt. Above them were the provincial administrators and the governor. Above all of these, of course, was the central government and the emperor. Each of these layers could issue orders to the local magistrate and each required reports and memorials from him.[8]

The county magistrate supervised units of control below the county level. These included village elders, local institutions, and self-rule organizations, especially the township (xiang), which had been made formal under the Han dynasty, and the baojia system, a system of mutual responsibility formally organized by Wang Anshi in the 11th century, during the Song dynasty. Under Mongol rule in the Yuan dynasty, the county magistrates were all Mongol, though their subordinates were Han Chinese.[9] In the Ming and Qing dynasties the growth of the economy and increase in population led magistrates to hire administrative secretaries and to rely on local elite families, or scholar-gentry. These local elites had friends whose influence could counteract the magistrate if he displeased them.[2]

When the People's Republic was founded in 1949, the central government once again appointed local officials who wielded civil, criminal, and bureaucratic power. Some suggest that workers and villagers feel they cannot question the authority of these "father and mother" officials, making corruption easier and dissent harder.[10]

Responsibilities and powers

The magistrate's responsibilities were broad but not clearly defined. The emperors believed that Heaven entrusted their government with relations with the physical universe, cosmic morality, human institutions, and social harmony, and the magistrate was his representative in all these matters.[11]

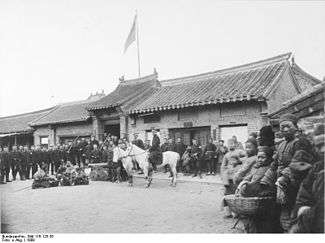

Yet the magistrate's power was circumscribed, as reflected in the saying "Heaven is high and the emperor far away." The county government bureaucracy was thin in relation to the population, and the official staff of a larger county might consist only of a magistrate, a vice-magistrate, perhaps an assistant magistrate or recorder, and the captain of the militia. As early as the 12th century this small group was expected to supervise a population that could easily be 150,000 in the more densely populated sections of the country.[12] In later dynasties, magistrates took on larger staffs. In the counties of the prosperous Lower Yangzi valley, the total staff of clerks, secretaries, yamen runners, medical examiners, jailers, and other such lesser employees might be some 500 people for a population of 100,000 to 200,000.[5] The eminent historian Kung-chuan Hsiao, however, argued that local government became more despotic and the county magistrate had unlimited powers to control the people.[13]

Tax collection and labor

The county government collected the land tax, grain tribute, and all other taxes except the customs duties and likin, which were introduced in the 19th century. The provincial treasurer prepared the quotas for the land and labor services tax due from each county according to the number of ding (male adults), as well as other taxes, and in theory adjusted the rates every ten years.[14] The magistrate also had responsibility for local infrastructure and communications. Each village was required to contribute free labor, or the corvee, for building and maintaining local roads, canals, and dams under the supervision of the county government.[15]

Taxes on the land were collected in silver, which was brought to the magistrate's court, where it was counted and recorded in his presence. He was allowed to keep a specified amount for local functions such as salaries, stipends for government school students, and relief for the poor, then forward the rest to the provincial treasurer. In later dynasties, the money assigned for local functions was too little, and magistrates imposed further fees and taxes, such as title deed taxes, brokerage tax, pawnshop tax, and many more.[16]

Law and judicial functions

After tax collection, law enforcement and legal disputes occupied the most of the magistrate's time and energy. Social harmony was paramount. The annual review for promotion graded the magistrate on his ability to catch thieves and prosecute robberies. One demerit was given for every five cases in which he arrested fewer than half the offenders and one merit for every five cases in which he arrested more than half.[17]

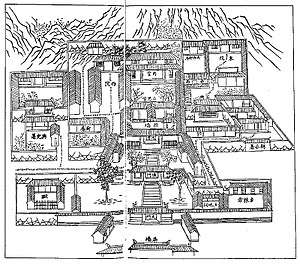

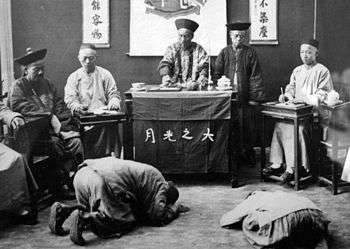

The magistrate lived, worked, and held court in the yamen, a walled compound which housed the local government. In theory, any commoner could submit a lawsuit, petition, or complaint after striking a large bell at the entrance to the compound.[18] The magistrate administered both judicial and administrative law. Scholars in the West once felt that the magistrate did not often become involved in civil disputes and that citizens were reluctant to bring them to the local courts, but research has shown that in fact local society was extremely litigious and that the local government was involved in all types of disputes.

Legal systems in some parts of the world distinguish civil, criminal, and administrative law, but under the Chinese legal system, the magistrate administered both judicial and administrative law. The magistrate was not allowed arbitrary decisions or to rely on local customary law but was constrained both by imperial edicts, which had the force of law, and the law codes. These dynastic law codes, such as the Tang Code or the Great Qing Code, included both civil law and criminal law. Cases ranged from murder and theft to accusations that a neighbor did not tie his horse or dog or that someone had been kicked or bitten. Litigants also went to the magistrate with disputes over marriage, adoption, inheritance, and land, and these often had consequences for country revenue or taxes and tax collection. The Codes described offenses in detail, but the magistrate was also allowed to make an analogy to an existing provision of the code by using the rule: "Everyone who does that which ought not to be done will receive forty strokes of the light bamboo. If the matter is adjudged to more serious, he will be punished by eighty strokes with the heavy bamboo." Death sentences under the Qing were reviewed by the emperor, and serious cases of any nature could be appealed or reviewed, sometimes even to the emperor himself.[11]

The magistrate, as in the inquisitorial system of continental European law, was both prosecutor and judge. He decided which cases to accept, directed the gathering of evidence and witnesses, then conducted the trial, including the use of torture. The magistrate was the sole judge of guilt or innocence and determined the punishment or compensation. Still, his decisions could be reviewed by higher officials, even up to the emperor in capital cases. Since he could be reprimanded for not investigating thoroughly, for not following correct procedure, or even for writing the wrong character, magistrates in later dynasties hired specialized clerks or secretaries who had expertise in the law and bureaucratic requirements.[11]

Yet law was not simply a matter of codes and procedures. Law was understood to reflect the moral universe, and a criminal or civil offense would throw that universe out of balance in a way that only just punishment could restore. The official Five Punishments (wu xing) prescribed under the Qing Code included beating with the light bamboo, beating with the heavy bamboo, penal servitude, exile, and execution. In calibrating punishment, the magistrate had to take into account not only the nature of the offense but the relation between the guilty party and the victim. An offense by a son against a father was far more serious than one by a father against a son, likewise an offense by a wife or other member of the family.[11]

The magistrate's role in practice faced many other constraints. The runners and yamen officials who were sent to investigate a crime were locals, often in league with the criminals. Magistrates commonly would therefore set a deadline for bringing in the criminals, threatening to take the policeman's family members as hostage if the deadline was not met. When the accused was brought before him, the magistrate could use torture, such as flogging or making the defendant kneel on an iron chain, but there were clear restrictions. The instruments had to be of a standard size and individually approved by the next higher yamen, and some could not be used on women or people over the age of seventy. The magistrate could order the use of the ankle-squeezer, for instance, only in cases of murder and robbery, and its use had to be specifically reported to the higher level. Some officials avoided the use of torture because they feared that it would produce false confessions. The magistrate had to make sure that any confession was recorded accurately, word for word, to prevent the clerk from introducing intentional errors that might prejudice the case. The magistrate himself could be punished if he invoked the wrong law or imposed a sentence that was either too harsh or too lenient.[17]

Schools and moral leadership

The magistrate oversaw and supported but did not administer education. Primary schools were established by families, temples, villages, or clans and were entirely private in their organization and finance. But the curriculum was almost entirely based on the Confucian texts needed to pass the imperial exams. The magistrate under the Qing dynasty conducted the reading of the Sacred Edict and conducted ceremonies and rituals, especially in time of drought, famine, or disaster.

Clerks and secretaries

The magistrate's wide-ranging duties in dealing with larger and larger populations required the help of secretaries, clerks, prison guards, and runners, but there was no budget to pay for this staff. Instead, the magistrate paid his secretaries from his own pocket, which he was expected to refill from local sources, and the other staff were expected to collect fees from those who were unlucky enough to come in contact with them. These fees might be arbitrary and extortionate, and in later dynasties corruption was widespread.[11]

Changes in late imperial China

Local government in the Ming and Qing dynasties accumulated responsibilities without increased resources. As the population grew, the number of counties remained roughly the same, with populations that could grow to perhaps 200,000. Ming rulers tightened the rule of avoidance which prevented magistrates from serving in their home districts, where it was justifiably feared that they would favor their friends and families, and the term of office was generally limited to two or three years. These rules ran the danger of posting magistrates to unfamiliar areas where they could not speak the local dialect and could not accumulate knowledge of local circumstances. The Qing government continued the Ming practice of requiring the magistrate to pay his subordinates from local taxes, not central government revenue; clerks, runners, jailers and such collected “informal fees” from the people. Confucian ideals also held that the state should stay out of the lives of the common people, who were to carry out public security functions on their own. The village head was responsible for tax collection, and the magistrate held him personally responsible for any shortfall.[19]

Under the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the last dynasty of imperial rule, local government became even more tightly stretched as population and wealth grew but government administrative institutions – and tax revenue – did not.[20] The magistrate was in a difficult situation. His salary had not risen with the long-term inflation. In the 1720s the Yongzheng Emperor allowed the magistrate to deduct "meltage fees" from the land tax he was required to remit, but this did not address the structural problem.[21] The unintended result was that by the early 19th century, major functions of local government had been abandoned by harried and underpaid magistrates and left to the gentry, who mediated disputes, supervised schools and irrigation works, organized local militia, and even collected taxes. Although magistrates were grateful to have this help, the local gentry often used these functions to reward themselves and punish their enemies.[19]

Magistrates in the Qing, however, also became more professional in several respects. They studied administration as a craft rather than something which a cultivated Confucian scholar-bureaucrat was expected to perform on the basis of moral training and knowledge of the Confucian classics. Since the emperor, in order to reward loyalty, increased the quota of those who were allowed to pass the exams without increasing the number of positions, there came to be more degree holders than there were entry level appointments. Many of these unassigned men took positions as secretaries or clerks to county magistrates, forming a virtual sub-profession of experts on various aspects of the law, water-works, taxation, or administration. Others, especially those who held only lower degrees, became tutors or local school teachers with little prestige or adequate income.[2]

Twentieth century and Republican China

The late Qing reforms of the early 20th century made basic changes. With the abolition of the centrally administered examination system, magistrates came to be selected by a local or ad hoc examinations, at least in theory, though recommendation and personal relations were more important in practice.[22] The law of avoidance remained in effect, though it too was no longer enforced rigorously, and the political chaos of the period was reflected in rapid turnover and shorter terms of office. One study found that most magistrates were appointed by the militarists who controlled the area. [23] In the years leading up to the founding of the Nationalist government in 1928, however, there was a noticeable improvement in the education and technical training of the magistrates, particularly in law and administration. The study also concluded that the civilian bureaucracy became more and more militarized.[24]

The County Organic Law, passed by the Nationalist government in 1928, defined the county as the basic level of government, and stipulated that the county magistrate, now called xianzhang, would be appointed by the provincial authorities. The county was supervised also by the Nationalist Party, which operated in parallel with the county government, an arrangement in accordance with the Party's Leninist structure. In addition, the new government organized a larger bureaucracy at the local level. [25]

During the Chinese Civil War, which lasted for several decades starting in 1927, the Communist Party of China built a bureaucratic base in many parts of China using the Soviet Union as a model.[26]

The People's Republic of China

After the Chinese Communist Revolution of 1949, local government took far more control of village life than had ever been possible in Chinese history, but local officials still faced many of the same problems as county magistrates under the empire. One foreign scholar wrote from his observations in 2015 that "grass-roots level civil servants are still seen as paternalistic 'father mother officials,' who are expected to take care of the ordinary people, enjoy a high degree of authority, but at the same time an equally high degree of mistrust." [27]

The magistrate in popular culture and literature

The magistrate was the hero in much popular fiction. The "detective story," for instance, in China took the form of the gong'an, or “court case,” in which the protagonist is not a private detective or police officer but the county magistrate, who is investigator, prosecutor, and judge. The magistrate solves a crime which has already been described to the reader, so that the suspense does not come not from discovering the criminal but from seeing how the magistrate solves the crime through clever stratagems.[28] Among these magistrate-detectives were the historical Tang dynasty official Di Renjie, who inspired a series of Judge Dee stories, and the Song dynasty official, Bao Zheng the hero of a set of stories and operas.

Since Chinese popular religion considered the world of life after death to closely resemble this one, the gods were part of a great bureaucracy which had the same structure as the imperial bureaucracy. The process of justice was pictured as being much the same in both worlds. The Magistrates of Hell presided over a court in much the way that the county magistrate did and their offices closely resembled the earthly ones.[29]

The short story "Execution of Mayor Yin" by Chen Ruoxi (in which "xianzhang" is translated as "Mayor") describes the career of Mayor Yin from the early 1950s through the Cultural Revolution and dramatizes the dilemma of an official who is caught between the necessity of serving both his superiors and his constituents.[30]

See also

- History of the administrative divisions of China

- History of the administrative divisions of China before 1912

- History of the administrative divisions of China (1912–49) (Republic of China on the mainland)

- History of the administrative divisions of China (1949–present) (People's Republic of China)

Notes

- Ch'u (1962), pp. 14–15.

- Watt (1972).

- Balazs (1965), p. 54.

- Spence (1990), p. 368.

- Wilkinson (2012), p. 261-262.

- Hsu Cho-yun, China A New Cultural History(New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 102, 104, 121.

- Qian (1982), p. 2, 14,.

- Ch'u (1962), pp. 6–7.

- Zhong (2003), p. 18- 46.

- Kwong, Julia (2015), The Political Economy of Corruption in China, New York: Routledge, p. 60, 80

- Tanner (2010), p. 49- 52.

- Mote (1999), p. 317.

- Hsiao (1967).

- Ch'u (1962), p. 130–131.

- Ch'u (1962), p. 131-l34.

- Ch'u (1962), p. 139, 144.

- Ch'u (1962), pp. 123–127.

- Ch'u (1962), p. 17.

- Wakeman (1975), p. 29–31.

- Ch'u (1962).

- Rowe (2009), p. 49- 52.

- Wou (1974), p. 217- 221.

- Wou (1974), p. 227- 231, 240.

- Wou (1974), p. 244-245.

- Zhong (2003), p. 34-36.

- Zhong (2003), p. 38-39.

- Traditions of Local Government Archived 2016-06-19 at the Wayback Machine The Yamen Runner 25 September 2015

- Ropp, Paul S. (1990), "The Distinctive Art of Chinese Fiction", in Ropp, Paul S. (ed.), The Heritage of China: Contemporary Perspectives, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-06441-0, p. 317.

- The Ten Magistrates of the Underworld Realm "Living in the Chinese Cosmos," Asia for Educators (Columbia University)

- Goldman, Merle (1979). "The Execution of Mayor Yin and Other Stories from the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. By Chen Jo-Hsi". Journal of Asian Studies. 38 (2): 371–373. doi:10.2307/2053453. JSTOR 2053453.

References

- Ch'u, T'ung-tsu (Qu, Tongzu) (1962). Local Government in China under the Ch'ing. Cambridge, Mass.: Council on East Asian Studies Distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674536789.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fitzgerald, John (2013). "From County Magistrate to County Head: The Role and Selection of Senior County Officials in Guangdong Province in the Transition from Empire to Republic". Twentieth-Century China. 38 (3): 254–279. doi:10.1353/tcc.2013.0044.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hsiao, Kung-ch'üan (1967). Rural China: Imperial Control in the Nineteenth Century. Seattle: University of Washington Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). Imperial China, 900-1800. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674445155.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Qian, Mu (1982). Traditional Government in Imperial China: A Critical Analysis. 中國歷代政治得失 (Zhong guo li dai zheng zhi de shi) Hong Kong 1952; translated by Chun-tu Hsueh, George O. Totten. Chinese University Press. ISBN 9789622012547.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rowe, William T. (2009). China's Last Empire: The Great Qing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674036123.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1990). The Search for Modern China. New York: Norton. p. 123. ISBN 0393973514.

county magistrate.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Tanner, Harold M. (2010). China a History: From the Great Qing Empire through the People's Republic. 2. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co. ISBN 9781603843027.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wakeman, Frederic E. (1975). The Fall of Imperial China. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0029336902.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link).

- Watt, John R. (1972). The District Magistrate in Late Imperial China. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231035357.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012), "Central & Local Government", Chinese History: A New Manual, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 253–268, ISBN 9780674067158CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wou, Odoric Y.K. (1974). "The District Magistrate Profession in the Early Republican Period: Occupational Recruitment, Training and Mobility". Modern Asian Studies. 8 (2): 217–245. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00005461.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zhong, Yang (2003). Local Government and Politics in China : Challenges from Below. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765611171.

isbn:0765611171.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Balazs, Etienne (1965), "A Handbook of Local Administrative Practice of 1793", Political Theory and Administrative Reality in Traditional China, London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, pp. 50–75CS1 maint: ref=harv (link).

- Dull, Jack L. (1990), "The Evolution of Government in China", in Ropp, Paul S. (ed.), The Heritage of China: Contemporary Perspectives, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 55–84, ISBN 0-520-06441-0

- Hsieh, Pao Chao (1925). The Government of China (1644-1911). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link). Still a useful overview.

- Huang, Liuhong (1984). A Complete Book Concerning Happiness and Benevolence: A Manual for Local Magistrates in Seventeenth-Century China. translated by Chu Djang. Tucson, Ariz.: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0816508208.. An annotated translation of the most popular of the magistrate's handbooks.

- Loewe, Michael (2011). Bing: From Farmer's Son to Magistrate in Han China. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 9781603846226. A leading scholar's imaginative reconstruction of a magistrate's career in the Han dynasty.