Zechariah 14

Zechariah 14 is the fourteenth (and the last) chapter in the Book of Zechariah in the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament of the Christian Bible.[1][2][3] This book contains the prophecies attributed to the prophet Zechariah, and is a part of the Book of the Twelve Minor Prophets.[4] This chapter is a part of a section (so-called "Second Zechariah") consisting of Zechariah 9–14.[5] It continues the theme of chapters 12–13 about the 'war preceding peace for Jerusalem in the eschatological future.'[6] It is written almost entirely in third-person prophetic discourse, with seven times references to the phrase 'that day'.[7]

| Zechariah 14 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Book | Book of Zechariah |

| Category | Nevi'im |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 38 |

Text

The original text was written in the Hebrew language. This chapter is divided into 21 verses.

Textual witnesses

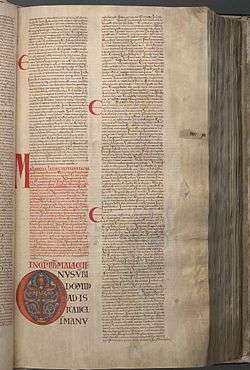

Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text, which includes the Codex Cairensis (from year 895), the Petersburg Codex of the Prophets (916), Aleppo Codex (930), and Codex Leningradensis (1008).[8][9]

Fragments containing parts of this chapter were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, that is, 4Q76 (4QXIIa; mid 2nd century BCE) with extant verses 18.[10][11][12][13]

There is also a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint, made in the last few centuries BC. Extant ancient manuscripts of the Septuagint version include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century), Codex Sinaiticus (S; BHK: S; 4th century), Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century) and Codex Marchalianus (Q; Q; 6th century).[14]

The Day of the Lord (14:1–15)

This section describes the cosmic picture of God gathering the nations to lay siege to Jerusalem and when half of the population has been exiles, God comes to deliver the city (2–3), defeating those opposing Jerusalem (verses 12–15).[15]

Verse 4

And his feet shall stand in that day upon the mount of Olives,

which is before Jerusalem on the east,

and the mount of Olives shall cleave in the midst thereof

toward the east and toward the west,

and there shall be a very great valley;

and half of the mountain shall remove toward the north,

and half of it toward the south.[16]

- "Mount of Olives": This mount lay on the east of Jerusalem, separated by the deep Kidron Valley, rising to a height of some 600 feet, and intercepting the view of the wilderness of Judaea and the Jordan ghor. It rises 187 feet above Mount Zion, 295 feet above Mount Moriah, 443 feet above Gethsemane, and lies between the city and the wilderness toward the Dead Sea and around its northern side, wound the road to Bethany and the Jordan. This verse is the only place in the Hebrew Bible (= Old Testament) where the name is exactly spelled, although it is often alluded to (e.g. 2 Samuel 15:30; 1 Kings 11:7; 2 Kings 23:13, where it is called "the mount of corruption", etc.).[17] There "upon the mountain, which is on the east side of the city, the glory of the Lord stood," when it had "gone up from the midst of the city" (Ezekiel 11:23).[18] The place of Jesus' departure at the time of ascension is located here and the same as the place of his return (in a similar "manner", Acts 1:11). Coming "from the east" (Matthew 24:27), Jesus made his triumphal entry into Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives (Matthew 21:1-10; cf. Ezekiel 11:23, with Ezekiel 43:2, "from the way of the east").[19]

- "Shall cleave in the midst thereof": The cleaving of the mount in two is by a fissure or valley (a prolongation of the "valley of Jehoshaphat" or "valley of decision" (Joel 3:2),[20] extending from Jerusalem on the west towards Jordan River, eastward. It results in an opening to escape for the besieged (cf. Joel 3:12, 14). Half the divided mount is thereby forced northward, half southward; the valley running between.[19]

Verse 5

And ye shall flee to the valley of the mountains;

for the valley of the mountains shall reach unto Azal:

yea, ye shall flee, like as ye fled from before the earthquake in the days of Uzziah king of Judah:

and the Lord my God shall come, and all the saints with thee.<ref>Zechariah 14:5 KJV</ref>

- "The earthquake in the days of Uzziah king of Judah": related to the one occurred two years before Amos prophesied in 8th century BCE (Amos 1:1) at the time when King Uzziah was stricken with a leprosy for invading the priest's office, according to Josephus,[21] Josephus wrote that at a place near the city called Eroge, half part of the mountain towards the west was broken, rolled then stood half a mile towards the eastern part, up to the king's gardens.[20]

The Nations Worship the King (14:16–21)

The survivors among the nations will come annually to Jerusalem to celebrate the Feast of Tabernacles, while those who don't come will be punished with no rain and plague.[22] Verses 20–21 depict a 'sanctified Jerusalem in ritual sense.'[23]

Eighth century BC earthquake

Research by Creationist Geology Professor Steven A. Austin[24] and colleagues published in 2000 suggested that widely separated archaeological excavations in the countries of Israel and Jordan contain late Iron Age (Iron IIb) architecture bearing damage from a great earthquake.[25] Earthquake debris at six sites (Hazor, Deir 'Alla, Gezer, Lachish, Tell Judeideh, and 'En Haseva), is tightly confined stratigraphically to the middle of the 8th century BC, with dating errors of ~30 years.[25] Excavations by archaeologist Yigael Yadin in Hazor's Stratum VI revealed southward tilted walls, inclined pillars, and collapsed houses, in even some of the strongest architecture, arguing that the earthquake waves were propagated from the north.[26] The excavation in the city of Gezer revealed severe earthquake damage. The outer wall of the city shows hewn stones weighing tons that have been cracked and displaced several inches off their foundation. The lower part of the wall was displaced outward (away from the city), whereas the upper part of the wall fell inward (toward the city) still lying course-on-course, indicating the sudden collapse of the wall.[27] A report in 2019 by geologists studying layers of sediment on the floor of the Dead Sea further confirmed this particular seismic event.[28]

Amos of Tekoa delivered a speech at the Temple of the Golden Calf in the city of Bethel in the northern kingdom of Israel just "two years before the earthquake" (Amos 1:1), in the middle of eighth century BC when Uzziah was king of Judah and Jeroboam II was king of Israel. Amos spoke of the land being shaken (Amos 8:8), houses being smashed (Amos 6:11), altars being cracked (Amos 3:14), and even the Temple at Bethel being struck and collapsing (Amos 9:1). The Amos' Earthquake impacted Hebrew literature immensely.[29] After the gigantic earthquake, no Hebrew prophet could predict a divine visitation in judgment without alluding to an earthquake. Just a few years after the earthquake, Isaiah wrote about the "Day of the Lord" when everything lofty and exalted will be abased at the time when the Lord "ariseth to shake terribly the earth" (Isaiah 2:19, 21). Then, Isaiah saw the Lord in a temple shaken by an earthquake (Isaiah 6:4).[29] Joel repeats the motto of Amos: "The Lord also will roar out of Zion, and utter his voice from Jerusalem," and adds the seismic theophany imagery "the heavens and the earth shall shake" (Joel 3:16; compare Amos 1:2). After describing a future earthquake and panic during the "Day of the Lord" at Messiah's coming to the Mount of Olives, Zechariah says, "Yea, ye shall flee, like as ye fled from before the earthquake in the days of Uzziah king of Judah" (Zechariah 14:5). The panic caused by Amos' Earthquake must have been the topic of legend in Jerusalem, because Zechariah asked his readers to recall that terrifying event 230 years later.[29]

In 2005 Nicholas Ambraseys reviews the literature on historical earthquakes in Jerusalem and specifically the 'Amos' earthquake. He states that "Modern writers date the earthquake to 759 BC and assign to it a magnitude of 8.2, with an intensity in Jerusalem between VIII and IX." He believes that such an earthquake "should have razed Jerusalem to the ground" and states that there is no physical or textual evidence for this. Discussing Zechariah's mention of an earthquake, he suggests that it was a 5th or 4th century insertion and discusses various versions of the passage which describe the event in different ways. He suggests that the differences may be due to a confused reading of the Hebrew words for "shall be stopped up" (ve-nistam), and "you shall flee" (ve-nastem)" and that "by adopting the latter reading as more plausible in relation to the natural phenomenon described, it is obvious that there is no other explanation than a large landslide, which may or may not had been triggered by this or by another earthquake." He also states that a search for changes in the ground resembling those described in Zechariah revealed "no direct or indirect evidence that Jerusalem was damaged."[30]

See also

- Related Bible parts: Amos 1, Zechariah 13, Luke 24, Acts 1

Notes and references

- Collins 2014, p. 428.

- Hayes 2015, Chapter 23.

- Zechariah, Book of. Jewish Encyclopedia

- Mason 1993, pp. 826-828.

- Coogan 2007, p. 1357 Hebrew Bible.

- Rogerson 2003, p. 728.

- Larkin 2007, p. 615.

- Würthwein 1995, pp. 35-37.

- Boda 2016, pp. 2–3.

- Boda 2016, p. 3.

- Dead sea scrolls – Zechariah

- Ulrich 2010, p. 623.

- Fitzmyer 2008, p. 38.

- Würthwein 1995, pp. 73-74.

- Mason 1993, p. 828.

- Zechariah 14:4 KJV

- Exell, Joseph S.; Spence-Jones, Henry Donald Maurice (Editors). On "Zechariah 14". In: The Pulpit Commentary. 23 volumes. First publication: 1890. Accessed 24 April 2019.

- Barnes, Albert. Notes on the Bible - Zechariah 14. James Murphy (ed). London: Blackie & Son, 1884. Reprint, Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1998.

- Jamieson, Robert; Fausset, Andrew Robert; Brown, David. Jamieson, Fausset, and Brown's Commentary On the Whole Bible. "Zechariah 14". 1871.

- Gill, John. Exposition of the Entire Bible. "Zechariah 14". Published in 1746-1763.

- Flavius Josephus, Antiquity. l. 9. c. 10. sect. 4.

- Rogerson 2003, pp. 728–729.

- Rogerson 2003, p. 729.

- "Steven A. Austin, Ph.D." Creation.com. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- Austin, S.A., G. W. Franz, and E. G. Frost. 2000. Amos's Earthquake: An extraordinary Middle East seismic event of 750 B.C. International Geology Review. 42 (7): 657-671.

- Yadin Y. 1975. Hazor, the rediscovery of a great citadel of the Bible. New York: Random House, 280 pp.

- Younker, R. 1991. A preliminary report of the 1990 season at Tel Gezer, excavations of the "Outer Wall" and the "Solomonic" Gateway (July 2 to August 10, 1990). Andrews University Seminary Studies. 29: 19-60.

- Fact-checking the Book of Amos: There Was a Huge Quake in Eighth Century B.C.E. By Ruth Schuster Haaretz, Jan 03, 2019. Quote: "An earthquake that ripped apart Solomon’s Temple was mentioned in the Bible and described in colorful detail by Josephus – and now geologists show what really happened."

- Ogden, K. 1992. The earthquake motif in the book of Amos. In Schunck, K., and M. Augustin, eds., Goldene apfel in silbernen schalen. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 69-80; Freedman, D.N., and A. Welch. 1994. Amos's earthquake and Israelite prophecy. In Coogan, M.D., J. C. Exum, and L. E. Stager, eds., Scripture and other artifacts: essays on the Bible, and archaeology in honor of Philip J. King. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 188-198.

- Ambraseys, N. (July 2005). "Historical earthquakes in Jerusalem – A methodological discussion". Journal of Seismology. 9 (3): 329–340. doi:10.1007/s10950-005-8183-8.

Sources

- Boda, Mark J. (2016). Harrison, R. K.; Hubbard, Jr, Robert L. (eds.). The Book of Zechariah. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0802823755.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, John J. (2014). Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Fortress Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coogan, Michael David (2007). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version, Issue 48 (Augmented 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288810.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (2008). A Guide to the Dead Sea Scrolls and Related Literature. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802862419.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hayes, Christine (2015). Introduction to the Bible. Yale University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Larkin, Katrina J. A. (2007). "37. Zechariah". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 610–615. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mason, Rex (1993). "Zechariah, The Book of.". In Metzger, Bruce M; Coogan, Michael D (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195046458.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ulrich, Eugene, ed. (2010). The Biblical Qumran Scrolls: Transcriptions and Textual Variants. Brill.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)