Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project

The Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project (Chinese: 夏商周断代工程; pinyin: Xià Shāng Zhōu Duàndài Gōngchéng) was a multi-disciplinary project commissioned by the People's Republic of China in 1996 to determine with accuracy the location and time frame of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties. Tsinghua University professor Li Xueqin was the director, and some 200 experts took part in the project, which correlated radiocarbon dating, archaeological dating methods, historical textual analysis, astronomy, and other methods to achieve greater temporal and geographic accuracy. Preliminary results of the project were released in November 2000. However, several of the project's methods and conclusions have been disputed by other scholars.

Background

The traditional account of ancient China, represented by the Records of the Grand Historian written by Sima Qian in the Han dynasty, begins with the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors, leading through a sequence of dynasties, the Xia, Shang and Zhou. Sima Qian felt able to give a year-by-year chronology back to the start of the Gonghe Regency in 841 BC, early in the Zhou dynasty. For the period before that date, his sources (now mostly lost) were unreliable and inconsistent, and he gave only lists of kings and accounts of isolated events. Later scholars were unable to push a precise chronology back past Sima Qian's date of 841 BC.[1]

Many elements of the traditional account, especially the early parts, were clearly mythical. In the 1920s, Gu Jiegang and other scholars of the Doubting Antiquity School noted that the earliest figures appeared latest in the literature, and suggested that the traditional history had accreted layers of myth. Noting parallels between the accounts of the Xia and Shang, they suggested that the history of the Xia was invented by the Zhou to support their doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven, by which they justified their conquest of the Shang. Some even doubted the historicity of the Shang dynasty.[2][3]

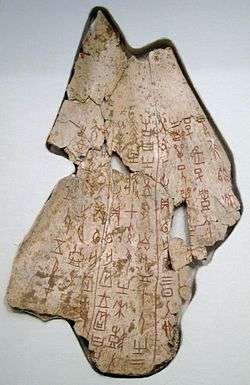

In 1899, the scholar Wang Yirong examined some curious symbols carved on "dragon bones" purchased from a Chinese pharmacist, and identified them as an early form of Chinese writing. The bones were finally traced back in 1928 to a site (now called Yinxu) near Anyang, north of the Yellow River in modern Henan province.[4] The inscriptions on the bones were found to be divination records from the reigns of the last nine Shang kings, from the reign of Wu Ding. Moreover, from the sacrificial schedule recorded on the bones it was possible to reconstruct a sequence of Shang kings that closely matched the list given by Sima Qian.[5]

Archaeologists focussed on the Yellow River valley in Henan as the most likely site of the states described in the traditional histories. After 1950, remnants of an earlier walled city of the Erligang culture were discovered near Zhengzhou, and in 1959 the site of the Erlitou culture was found in Yanshi, south of the Yellow River near Luoyang. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the Erlitou culture flourished c. 2100 BC to 1800 BC. They built large palaces, suggesting the existence of an organized state.[6] More recently the picture has been complicated by the discovery of advanced civilizations in Sichuan and the Yangtze valley, such as Sanxingdui, Panlongcheng and Wucheng, of which the traditional histories make no mention.[7]

Until the mid-20th century, many popular works, both Chinese and Western, used a traditional chronology calculated by Liu Xin early in the first century AD. However, modern scholars studying inscriptions on Shang oracle bones and Zhou bronzes were proposing shorter chronologies, for example typically placing the Zhou conquest of the Shang in the mid-11th century BC instead of the 12th.[8]

In 1994, Song Jian, a state councillor for science, was impressed on a visit to Egypt by chronologies stretching back to the 3rd millennium BC. He proposed a multi-disciplinary project to establish a similar chronology for China. The project was approved as part of the ninth five-year plan (1996–2000).[9][10]

Methods

The Project used a combination of methods to attempt to correlate the traditional literature with archeological discoveries and the astronomical record.[11]

Western Zhou kings

The contemporary evidence for the Western Zhou consists of thousands of bronzes, many bearing inscriptions. Around 60 of these record dates of important events as the day in the sexagenary cycle, the phase of the moon, the month and the year of reign. However the king is usually not identified.[12]

Occasionally an unusual astronomical event was recorded. A key reference point was the accession of King Yi of Zhou, when according to the "old text" Bamboo Annals the day dawned twice. The Project adopted (without acknowledgement) the proposal of the Korean scholar Pang Sunjoo (方善柱) that this referred to an annular solar eclipse at dawn that occurred in 899 BC.[13] Other scholars have challenged both this interpretation of the text and the astronomical calculations involved.[14][15]

King Wu's conquest of the Shang

Perhaps the most significant event requiring dating is the conquest of the Shang by the Zhou, described in traditional histories as the Battle of Muye, though the site of the battle has not been identified. Previous chronologies had proposed at least 44 different dates for this event, ranging from 1130 to 1018 BC.[11][16] The most popular have been 1122 BC, calculated by the Han dynasty astronomer Liu Xin, and 1027 BC, deduced from a statement in the "old text" Bamboo Annals that the Western Zhou (whose end point is known to be 770 BC) had lasted 257 years.[17][18]

A few documents relate astronomical observations to this event:

- A quotation in the Book of Han from the lost Wǔchéng 武成 chapter of the Book of Documents appears to describe a lunar eclipse just before the beginning of King Wu's campaign. This date, and the date of his victory, are given as months and sexagenary days.[19][20]

- A passage in the Guoyu gives the positions of the Sun, Moon, Jupiter and two stars on the day King Wu attacked the Shang.[18][20]

- The "current text" Bamboo Annals mentions conjunctions of all five planets occurring before and after the Zhou conquest. Han-period texts mention the first conjunction as occurring in the 32nd year of the reign of the last king. Such events are rare, but all five planets did gather on 28 May 1059 BC and again on 26 September 1019 BC. Although the recorded positions in the sky of these two events are the reverse of what occurred, they could not have been retrospectively calculated at the time the account first appears.[21]

The strategy adopted by the Project was to use archeological investigation to narrow the range of dates that would need to be compared with the astronomical data. Although no archaeological traces of King Wu's campaign have been found, the pre-conquest Zhou capital at Fengxi in Shaanxi has been excavated and strata at the site have been identified with the pre-dynastic Zhou. Radiocarbon dating of samples from the site as well as at late Yinxu and early Zhou capitals, using the wiggle matching technique, yielded a date for the conquest between 1050 and 1020 BC. The only date within that range matching all the astronomical data is 20 January 1046 BC. This date had previously been proposed by David Pankenier, who had matched the above passages from the classics with the same astronomical events, but here it resulted from a thorough consideration of a broader range of evidence.[22][23][24]

Other scholars have raised several criticisms of this process. The connection between the layers at the archaeological sites and the conquest is uncertain.[25] The narrow range of radiocarbon dates are cited with a less stringent confidence interval (68%) than the standard requirement of 95%, which would have produced a much wider range.[26] The texts describing the relevant astronomical phenomena are extremely obscure.[27][28] For example, the inscription on the Li gui, a key text used in dating the conquest, can be interpreted in several different ways, with one alternative reading leading to the date of 9 January 1044 BC.[18]

Late Shang kings

For the late Shang, the oracle bones provide less detail than Zhou bronzes, routinely recording only the day in the sexagenary cycle. However, calculations using a longer ritual cycle were used to date the reigns of the last two Shang kings.[29] Mentions of five lunar eclipses in oracle bone divinations from the late Wu Ding and Zu Geng reigns were identified with events spanning the period from 1201 and 1181 BC, from which a start date for Zu Geng's reign was derived.[29][30] The start of date of Wu Ding's reign was then calculated using the statement in the "Against Luxurious Ease" chapter of the Book of Documents that his reign lasted 59 years.[31]

Early Shang and Xia

According to the traditional histories, Pan Geng, three reigns earlier than Wu Ding, moved the Shang capital to its last site, generally identified with the Yinxu site in Anyang. Different interpretations of the text of the Bamboo Annals give intervals of 275, 273 or 253 years between this event and the Zhou conquest. The project settled on a date near the shortest of these intervals.[32]

The four phases of the Erlitou culture have been divided between the Xia and Shang dynasties in different ways by various prominent archaeologists.[33] The project assigned all four phases to the Xia, identifying the establishment of the Shang dynasty with the building of the Yanshi walled city 6 km (3.7 mi) north-east of the Erlitou site.[34] The time span of the Xia dynasty was taken from reign-lengths given in the Bamboo Annals and from a conjunction of five planets during the reign of Yu the Great recorded in later texts. As this period was longer than the time spanned by the Erlitou culture, the project also included the later phases of the Wangwan III variant of the Longshan culture within the Xia period.[34]

Chronological table

The Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project concluded precise dates for accessions of rulers from Wu Ding, the Shang dynasty king whose reign produced the oldest known oracle bone records. These dates are here compared with the traditional dates and those used in the Cambridge History of Ancient China:[35][36][37]

| Dynasty | King | Accession date (BC) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XSZ Project | Cambridge History | Traditional | ||

| Shang | Wu Ding | 1250 | before 1198 | 1324 |

| Zu Geng | 1191 | after 1188 | 1265 | |

| Zu Jia | – | c. 1177 | 1258 | |

| Lin Xin | – | c. 1157 | 1225 | |

| Kang Ding | – | c. 1148 | 1219 | |

| Wu Yi | 1147 | c. 1131 | 1198 | |

| Wen Ding | 1112 | c. 1116 | 1194 | |

| Di Yi | 1101 | 1105 | 1191 | |

| Di Xin | 1075 | 1086 | 1154 | |

| Zhou | King Wu | 1046 | 1045 | 1122 |

| King Cheng | 1042 | 1042 | 1115 | |

| King Kang | 1020 | 1005 | 1078 | |

| King Zhao | 995 | 977 | 1052 | |

| King Mu | 976 | 956 | 1001 | |

| King Gong | 922 | 917 | 946 | |

| King Yi | 899 | 899 | 934 | |

| King Xiao | 891 | 872? | 909 | |

| King Yi | 885 | 865 | 894 | |

| King Li | 877 | 857 | 878 | |

Earlier dates are given more approximately:[37][34][38]

- The relocation of the Shang capital to Yin during the reign of Pan Geng is aligned with the earliest layers at Yinxu, dated at c. 1300 BC.

- The establishment of the Shang dynasty was identified with the foundation of an Erligang culture walled city at Yanshi, dated at c. 1600 BC, compared with the Cambridge History's c. 1570 BC and the traditional date of 1766 BC.

- The establishment of the Xia dynasty was dated at c. 2070 BC, compared with the traditional date of 2205 BC.

Reception

Coverage of the project in non-Chinese press focused on the conflict between nationalism and scholarship.[39][40] The project was criticized for being a major political project rather than a major archaeological project with the purpose to glorify the Chinese nation, and boasting the ethnocentric nationalism in China, which may raise frictions with its neighbors.[40] However, Yun Kuen Lee observes that not every member of the chronology project agrees on all of the dates. Indeed, the project has been unafraid to contest dates proposed even by the director. Lee points out that this is a strong sign that the dates are being considered on their own merits rather than by deferring to authority, and that politics does not influence the detailed work of the project.[41]

In addition to methodological concerns, scholars have complained that the project is part of a tradition of relegating archaeology to a role of verifying traditional histories. They argue that this forces archeological evidence into a framework of a single sequence of similar dominant states, as depicted in the histories and reflected in the title "Three Dynasties". However, when evaluated on its own merits, the evidence reveals a much more complex origin of Chinese civilization, with many other advanced states that are not mentioned in the histories.[42]

A preliminary report of the project was issued in 2000.[37] A session of the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in 2002 was devoted to the report, where its methods were criticised by David Nivison, among others.[43][44] No further report has been issued. An international conference on chronology arranged for October 2003 was postponed due to the SARS outbreak, but never rescheduled.[45] The Project's dates have however become the orthodox chronology in Chinese textbooks and reference works.[46]

References

Footnotes

- Lee (2002a), pp. 16–17.

- Lee (2002a), p. 21.

- Wagner (1993), p. 10.

- Fairbank & Goldman (2006), p. 33.

- Keightley (1999), pp. 234–235.

- Fairbank & Goldman (2006), pp. 33–35.

- Bagley (1999), pp. 124–125.

- Shaughnessy (1999), pp. 23–24.

- Shaughnessy (2011), p. 274.

- Lee (2002a), p. 17.

- Yin (2002), p. 1.

- Lee (2002a), pp. 29–30.

- Shaughnessy (2009), p. 24.

- Keenan (2002), p. 62.

- Stephenson (2008), pp. 238–239.

- Lee (2002a), p. 32.

- Pankenier (1981–1982), p. 3.

- Lee (2002a), p. 34.

- Lee (2002a), pp. 33–34.

- Liu (2002), p. 4.

- Zhang (2002b), p. 350.

- Lee (2002a), pp. 31–34.

- Yin (2002), pp. 2–3.

- Pankenier (1981–1982), pp. 3–7.

- Lee (2002a), p. 36.

- Keenan (2007), p. 147.

- Keenan (2002), pp. 62–64.

- Stephenson (2008), pp. 231–242.

- Lee (2002a), p. 31.

- Liu (2002), pp. 3–4.

- Zhang (2002b), p. 352.

- Li (2002), p. 331.

- Lee (2002b), p. 377.

- Li (2002), p. 332.

- Shaughnessy (1999), p. 25.

- Mathews (1943), p. 1166.

- XSZCP Group (2000).

- Lee (2002a), p. 28.

- Eckholm (2000).

- Gilley (2000).

- Lee (2002a), pp. 35–36.

- Lee (2002a), pp. 20–21, 36.

- Session 79: The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project: Defense and Criticism Archived February 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, AAS Annual Meeting, Washington, 2002.

- Nivison (2002).

- Shaughnessy (2011), p. 276.

- Shaughnessy (2009), p. 25.

Works cited

- Bagley, Robert (1999), "Shang archaeology", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 124–231, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Eckholm, Erik (November 10, 2000), "In China, Ancient History Kindles Modern Doubts", New York Times, p. A3.

- Gilley, Bruce (July 20, 2000), "Digging into the Future", Far Eastern Economic Review, pp. 74–77, archived from the original on April 13, 2001.

- Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006), China: A New History (2nd ed.), Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01828-0.

- Keenan, Douglas J. (2002), "Astro-historiographic chronologies of early China are unfounded" (PDF), East Asian History, 23: 61–68.

- ——— (2007), "Defence of planetary conjunctions for early Chinese chronology is unmerited" (PDF), Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 10: 142–147.

- Keightley, David N. (1999), "The Shang: China's first historical dynasty", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 232–291, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Lee, Yun Kuen (2002a), "Building the chronology of early Chinese history", Asian Perspectives, 41 (1): 15–42, doi:10.1353/asi.2002.0006, hdl:10125/17161.

- ——— (2002b), "Differential Resolution in History and Archaeology", Journal of East Asian Archaeology, 4: 375–386, doi:10.1163/156852302322454639.

- Li, Xueqin (2002), "The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project: Methodology and Results", Journal of East Asian Archaeology, 4: 321–333, doi:10.1163/156852302322454585.

- Liu, Ci-Yuan (2002), "Astronomy in the Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project", Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 5 (1): 1–8, Bibcode:2002JAHH....5....1L.

- Mathews, Robert Henry (1943), A Chinese-English Dictionary Compiled for the China Inland Mission, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-12350-2.

- Nivison, David (2002), "The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project: Two Approaches to Dating", Journal of East Asian Archaeology, 4: 359–366, doi:10.1163/156852302322454611.

- Pankenier, David W. (1981–1982), "Astronomical Dates in Shang and Western Zhou" (PDF), Early China, 7: 2–37.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1999), "Calendar and Chronology", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 19–29, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- ——— (2009), "Chronologies of Ancient China: A Critique of the 'Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project'" (PDF), in Ho, Clara Wing-chung (ed.), Windows on the Chinese World: Reflections by five historians, Lexington Books, pp. 15–28, ISBN 978-0-7391-2769-8, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-15.

- ——— (2011), "Of Riddles and Recoveries: The Bamboo Annals, Ancient Chronology, and the Work of David Nivison" (PDF), Journal of Chinese Studies, 52: 269–290.

- Stephenson, F. Richard (2008), "How reliable are archaic records of large solar eclipses?", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 39: 229–250, Bibcode:2008JHA....39..229S, doi:10.1177/002182860803900205.

- Wagner, Donald B. (1993), Iron and Steel in Ancient China, Brill Publishers, ISBN 978-90-04-09632-5.

- XSZCP Group (2000), 夏商周断代工程1996—2000年阶段成果报告: 简本 [The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project Report for the years 1996–2000 (abridged)], Beijing: 世界图书出版公司, ISBN 978-7-5062-4138-0, archived from the original on 2010-12-29.

- Yin, Weizhang (2002), trans. Victor Cunrui Xiong, "New development in the research on the chronology of the Three Dynasties" (PDF), Chinese Archaeology, 2: 1–5.

- Zhang, Changshou (2002a), "The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project: Excavations of the Proto-Zhou Culture in Fengxi, Shaanxi", Journal of East Asian Archaeology, 4: 335–346, doi:10.1163/156852302322454594.

- Zhang, Peiyu (2002b), "Determining Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology through Astronomical Records in Historical Texts", Journal of East Asian Archaeology, 4: 335–357, doi:10.1163/156852302322454602.