Woolpit

Woolpit is a village in the English county of Suffolk, midway between the towns of Bury St. Edmunds and Stowmarket. In 2011 Woolpit parish had a population of 1,995.[1] It is notable for the 12th-century legend of the green children of Woolpit and for its parish church, which has especially fine medieval woodwork. Administratively Woolpit is a civil parish, part of the district of Mid Suffolk.

| Woolpit | |

|---|---|

Church of St Mary | |

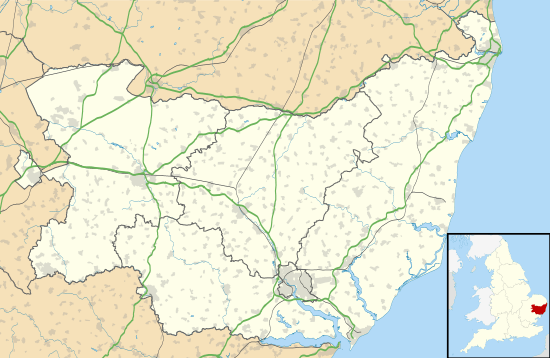

Woolpit Location within Suffolk | |

| OS grid reference | TL973624 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Bury St Edmunds |

| Postcode district | IP30 |

History

The village's name, first recorded in the 10th century as Wlpit and later as Wlfpeta, derives from the Old English wulf-pytt, meaning "pit for trapping wolves".[2]

Before the Norman conquest of England, the village belonged to Ulfcytel Snillingr.[3] Between 1174 and 1180, Walter de Coutances, a confidant of King Henry II, was appointed to Woolpit. After his "death or retirement" it was to be granted to the monks of Bury St Edmunds Abbey. A bull of Pope Alexander III likewise confirms that revenues from Woolpit are to be given to the abbey.[4]

In the 15th century and for some time afterward, two fairs were held annually. The Horse Fair was held on two closes, or fields, on 16 September. The Cow Fair was held on its own field on 19 September; here toys as well as cattle were sold.

Sir Robert Gardiner, Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, was Lord of the Manor from 1597 to 1620. He founded an almshouse for the care of the poor women of Woolpit and nearby Elmswell. The Gardiner charity still exists. Woolpit passed at his death to his grandnephew, Gardiner Webb, who died in 1674.

From the 17th century, the area became an important manufacturing centre for "Suffolk White" bricks, but today only the pits remain.

Woolpit is in the hundred of Thedwestry, 8 miles (13 km) southeast of Bury. The area of the parish is 2,010 acres (8.1 km2); the population in 1831 was 880, less than half agricultural.

Mill Lane marks the site of a post mill which was demolished in about 1924. Another mill, which fell down in 1963, stood in Windmill Avenue.

The village contains two pubs, The Bull and The Swan, two tea rooms, estate agents, a grocers, hairdressers, fish and chip shop, Palmers Bakery, a dentist and Woolpit Interiors within the village and two industrial estates containing more larger businesses as well as a health surgery and school.

Demographics

In 1811, Woolpit had 625 inhabitants in 108 houses. By 1821 the population had increased to 801 inhabitants in 116 houses.[3]

Legend of the Green Children

The medieval writers Ralph of Coggeshall and William of Newburgh report that two children appeared mysteriously in Woolpit some time during the 12th century. The brother and sister were of generally normal appearance except for the green colour of their skin. They wore strange-looking clothes, spoke in an unknown language, and the only food they would eat was raw beans. Eventually they learned to eat other food and lost their green pallor, but the boy was sickly and died soon after the children were baptised.[5] The girl adjusted to her new life, but she was considered to be "rather loose and wanton in her conduct".[6] After learning to speak English she explained that she and her brother had come from St Martin's Land, an underground world whose inhabitants are green.[5]

Some researchers believe that the story of the green children is a typical folk tale, describing an imaginary encounter with the inhabitants of another world, perhaps one beneath our feet or even extraterrestrial. Others consider it to be a garbled account of an historical event, perhaps connected with the persecution of Flemish immigrants living in the area at that time.[5]

Local author and folk singer Bob Roberts stated in his 1978 book A Slice of Suffolk that, "I was told there are still people in Woolpit who are 'descended from the green children', but nobody would tell me who they were!"[5]

St Mary's Church

The Grade I listed church[7] has "Suffolk's most perfectly restored angel hammerbeam roof",[8] a profusion of medieval carved pew-ends (mixed with good 19th-century recreations), and a large and very fine porch of 1430–55. The roof is actually a double hammerbeam example, with the upper beam being false. The tower and spire are by Richard Phipson in the 1850s, replacing the originals lost to lightning in 1852 or 1853. Most of the rest of the church is Perpendicular, except for the 14th-century south aisle and chancel. There is fine flushwork decoration on the exterior of the clerestory. The medieval shrine was at the east end of the south aisle.[9] The "quite perfect"[3] eagle lectern is a rare early-Tudor original from before the English Reformation.[10]

Our Lady of Woolpit

Until the Reformation the church housed a richly adorned statue of the Virgin Mary known as "Our Lady of Woolpit", which was an object of veneration and pilgrimage, perhaps as early as about 1211.[11] There is a clear indication of the existence of an image of the Virgin in a mid-15th century will that speaks of "tabernaculum beate Mariae de novo faciendo" ("in making new/anew the tabernacle of Blessed Mary"), which sounds at least like a canopy or even a chapel for housing an image.[12] It stood in its own chapel within the church. No trace of the chapel survives, but it may have been situated at the east end of the south aisle, or more probably on the north side of the chancel in the area now occupied by the 19th-century vestry.[11]

Pilgrimage to Our Lady of Woolpit seems to have been particularly popular in the 15th and early 16th centuries, and the shrine was visited twice by King Henry VI, in 1448 and 1449.[13]

In 1481 John, Lord Howard (from 1483 created Duke of Norfolk by Richard III), left a massive £7 9s as an offering for the shrine.[14]

After the Tudor dynasty had consolidated its hold on the English throne, Henry VII's queen, Elizabeth of York, made a donation in 1502 of 20d to the shrine.[15]

The statue was removed or destroyed after 1538, when Henry VIII ordered the taking down of "feigned images abused with Pilgrimages and Offerings" throughout England; the chapel was demolished in 1551, on a warrant from the Court of Augmentations.[11]

The Lady's Well

In a field about 300 yards north-east of the church there is a small irregular moated enclosure of unknown date, largely covered by trees and bushes and now a nature reserve. The moat is partially filled by water rising from a natural spring, protected by modern brickwork, on the south side; the moated site and the spring constitute a scheduled ancient monument.[16][17]

The spring is known as the Lady's Well or Lady Well. Although there are earlier references to a well or spring, it is first named as "Our Ladys Well" in a document dated between 1573 and 1576, referring to a manorial court meeting in 1557–58.[11] The name suggests that it was once a holy well dedicated like the church and statue to the Virgin Mary, and it has been suggested that the well itself was a place of medieval pilgrimage.[18] There is no evidence to suggest that there was ever a building at the site of the well,[11] or even to support the claim of its being a specific goal of pilgrimage. In fact the well was on land held not by the parish church but by the chapel of St John at Palgrave.

At some unknown point, a local tradition arose that the waters of the spring had healing properties.[11] A writer in 1827 described the Lady's Well as

a perpetual spring about two feet deep of beautifully clear water, and so cold that a hand immersed in it is very soon benumbed. It is used occasionally for the immersion of weakly children, and much resorted to by persons of weak eyes.[3]

Analysis of the water in the 1970s showed that it has a high sulphate content, which may have been of some benefit in the treatment of eye infections.[11]

Notable residents

- Dr Helen Geake – archaeologist and a member of Channel 4's Time Team.

- Ian Lavender – actor and last surviving cast member of the Dad's Army platoon.

Notes

- Action with Communities in Rural England (2013). "Rural Community Profile for Woolpit (Parish)" (PDF). www.woolpit.org. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- Mills, A. D. (2003), "Woolpit", A Dictionary of British Place-Names, Oxford University Press, retrieved 25 April 2009

- A concise description of Bury St. Edmund's: and its environs, within the distance of ten miles, London: Longman, 1827, pp. 357–61

- Arnold, Thomas (1896), Memorials of St. Edmund's abbey: Cronica Buriensis, 1020–1346, H. M. Stationery, pp. 84–85

- Clark, John (2006), "'Small, Vulnerable ETs': The Green Children of Woolpit", Science Fiction Studies, 33 (2): 209–229

- Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Steve (2000), "Green Children", A Dictionary of English Folklore ((subscription or UK public library membership required)) (online ed.), Oxford University Press, retrieved 5 April 2009

- Historic England. "Church of St Mary (1181376)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Suffolk Churches

- Norwich; Jenkins; Suffolk Churches

- Jenkins, Suffolk Churches

- Paine, Clive (1993). "The chapel and well of Our Lady of Woolpit". Proceedings of Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. 38 (1): 8–12.

- Nicholas Pevsner, Suffolk, Harmondsworth, 1961, p. 503

- Webb, Diana (2000). Pilgrimage in Medieval England. London, New York: Hambledon and London. pp. 99–100, 136. ISBN 185285250X.

- John Ashdown-Hill Suffolk Connections of the House of York, in Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archeology and History 41 (2006) part 2, p. 203

- John Ashdown-Hill Suffolk Connections of the House of York, in Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archeology and History 41 (2006) part 2, p. 203

- Historic England. "Lady's Well (holy well and moat) (1005992)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "Suffolk HER Number: WPT 002". Suffolk Historic Environment Record. Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- Hope, Robert Charles (1893). The Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England. London: Elliot Stock. p. 163.

References

- Jenkins, Simon, England's Thousand Best Churches, 1999, Allen Lane, ISBN 0-7139-9281-6

- John Julius Norwich, The Architecture of Southern England, Macmillan, London, 1985, ISBN 0-333-22037-4

- Suffolk Churches Illustrated details about the parish church

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Woolpit. |