Women in the United States Prohibition movement

The Temperance movement began long before the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was introduced. Across the country different groups began lobbying for temperance by arguing that alcohol was morally corrupting and hurting families economically, when men would drink their family's money away. This temperance movement paved the way for some women to join the Prohibition movement, which they often felt was necessary due to their personal experiences dealing with drunk husbands and fathers, and because it was one of the few ways for women to enter politics in the era. One of the most notable groups that pushed for Prohibition was the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. On the other end of the spectrum was the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform, who were instrumental in getting the 18th Amendment repealed. These women argued that Prohibition was a breach of the rights of American citizens and frankly ineffective due to the prevalence of bootlegging.

Origin

Women's Crusade

The Women's Crusade was the precursor to the Women's Christian Temperance Union. It was also known as the Women's Praying Crusade in response to their tactic of praying publicly in front of saloons.[1] It started as a religious group, motivated by their determination to end the alcoholism that they saw as a social ill. The Crusade was organized in Ohio in 1874 and created an opportunity for women to promote national temperance. Unlike the WCTU, the Women's Crusade was not a political organization and had the sole focus of temperance.[2]

The movement started due to the lectures given by Dr. Diocletian Lewis, who told the story of his mother getting a saloon to close by praying and singing. Though his techniques had been tried before, they had had limited success. The movement began to have success in Hillsboro, Ohio, where men and women who heard his lecture excitedly decided to try his methods. Men provided financial and emotional support, but women were the face of the movement. Hillsboro had moderate success, but it was after another one of Lewis’ lectures in Washington Court House, Ohio, that the movement really began to have success.[3]

After Hillsboro and Washington Court House, crusades erupted in small towns all over Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. There was some success in towns like Philadelphia, but the most successful crusades were in smaller towns. Nationwide a total of 750 breweries closed, and many shopkeepers pledged to sell alcohol only to those with prescriptions.[3]

The tactics of the movement involved picketing, praying and singing hymns publicly, marching in the streets, and asking for pledges from local shopkeepers and saloon owners. Saloons that were particularly harsh towards the crusaders would often have women stand in front of their doors, blocking entry, such was the case at a saloon in Adrian, Michigan after the saloon owner locked two of the women leaders in the saloon.[3]

Not all women supported the movement. Some women spat at the crusaders alongside their male companions, either because they felt it wasn't a woman's place to act so publicly, or because they didn't support temperance. Whatever the reason, many women and men saw drinking as a serious moral issue and supported the crusaders.[3]

Populist Party

The Populist party faced divisions within itself, but the majority of its members were individually for the Prohibition Reform. However, they never officially announced where they stood on their view of the movement as a collective group. Francis E. Willard was one of many who urged the Populist party to make an official statement. She tried to fuse the WCTU with the Prohibition party because they seemed to be making an impact on Populist members. She received opposition in her attempt because the Prohibition party didn't feel ready to support Women's Suffrage on top of what they were already trying to reform. However, the Populist party still had allies such as James Baird Weaver and Ignatius Donnelly who were in full support of both Prohibition and Women's Suffrage.[4]

Women's Christian Temperance Union

The Women's Christian Temperance Union was organized on November 18, 1874 in Cleveland, Ohio.[3] It quickly became the largest women's organization in the United States. The women in the movement were inspired by the serious drinking problem in the United States and the disproportionate ills that befell women whose husbands were drunkards. It was seen as both a moral and home issue, allowing women to join the political sphere in unprecedented ways.[3]

Men were barred from voting and holding office within the movement, though they were asked to contribute financially.[3]

The Women's Christian Temperance Union was founded by Annie Wittenmyer in 1874. In 1879 Frances E. Willard became the new president and remained president until her death.[5] The organization did not purely focus on temperance, but also promoted other social controls and the issue of equality for women. These other issues were part of Willard's “Do Everything” policy.[6]

The WCTU was united under a common leader, Willard, but had significant autonomy for local chapters. Willard often traveled the country to promote the WCTU and visit local chapters.[6] She visited Texas in 1882 [5] and California in 1883.[6] These visits inspired rapid membership growth.[6]

Notable Women in the Movement

There were many women that gained prominence during the Prohibition era, whether supporting or fighting the 18th Amendment. Among them were Presidents and members of the WCTU, and founders of the WONPR.

Annie Wittenmyer

Annie Wittenmyer was born Annie Turner in Ohio in 1827.[7] After the Civil War, Annie aligned herself with the Women's Crusade. She went to a convention in Cleveland, Ohio, where the Women's Christian Temperance Union was formed and she was voted as the first official president. Annie worked closely with Frances Willard, who was the secretary. They had opposing views regarding the WCTU's involvement in women's suffrage, so Annie became president of a new faction, the Non-Partisan Women's Christian Temperance Union (the group would not involve itself with women's suffrage).[7]

Frances Willard

Frances Willard was born September 28, 1839 in New York. She was a founder of the Women's Temperance Union and President from 1879 until her death in 1898.[8]

Willard was a very spiritual woman due to her upbringing and a brush with death when she was 19. She was very interested in the Women's Crusade, and eventually became the President of the Chicago chapter of the Women's Christian Temperance Union, despite a higher paying job offer at a college. Five years later she was voted into the Presidency of the entire Women's Christian Temperance Union. As the President, she gained national recognition and was praised for her competence.[2]

Frances Willard toured Texas in 1882 in order to organize WCTU chapters. It was at the end of a larger tour through the South. The movement struggled in the more conservative southern states, but her tour garnered large crowds and some success. It did not achieve long-term success and Texas prohibitionists maintained their separation from the northern based prohibition movement and Willard herself.[5]

Carrie A. Nation

Carrie Nation, originally Carrie Amelia Moore, was born in Kentucky in 1846. Her name is also sometimes spelled Carry.[9] She is most famous for her extreme opposition of alcohol and taking action by destroying bars and saloons with a hatchet. Carrie was very religious and would often pray or sing while swinging her hatchet across the United States. During her time and in history books, Carrie has been depicted as unnecessarily violent and domineering in her support of the Prohibition movement. No group claims that she was a part of what they stood for (feminists, various Christian religions, the WCTU).[10]

Carrie also published The Smasher’s Mail newspaper where people sent in their reactions to the destroying of saloons, which Carrie saw as a noble cause. Some people praised her actions, while others were more than angry with the way she handled violations of the Prohibition.[11]

Anna Gordon

Anna Gordon was born in Boston on July 21, 1853. She joined the Women's Christian Temperance Union after becoming Frances Willard’s private secretary.[12]

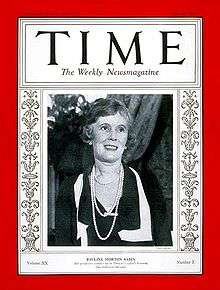

Pauline Morton Sabin

Pauline Morton Sabin was born in 1887 to a wealthy family. After her divorce and subsequent remarriage to Charles Hamilton Sabin, she became involved in charity and political work. She organized Republican meetings and parties on her estate, leading her to eventually found the National Women’s Republican Club in 1921.[13] She was the first woman to serve on the National Republican Committee.[14] She continued work in politics, eventually campaigning for Herbert Hoover in the 1928 election.[13]

Her work in Prohibition was inspired by her distaste for the hypocrisy of politicians who supported Prohibition only in public and the clear ineffectiveness of the law. She had supported Herbert Hoover, a Prohibitionist, but after his inaugural address decided to organize the anti-Prohibitionist women of America against the party’s platform.[13]

Opposition

There was opposition to Prohibition during and after the fight for it. The belief that women would vote as a block, a widespread fear during the suffrage movement, was proven wrong with the development of the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform. There were also many women who joined auxiliary groups to fight alongside their husbands or other male relations against the 18th Amendment.

Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform

The Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform was organized on May 28th, 1929 in Chicago. Five national committees were formed, including: Investigation, Publicity, Speakers’ Bureau, Legislative, and Membership. The organization was financed by voluntary contributions and not membership dues.[15] At their peak they had over a million members.[13] The primary founder, Pauline Morton Sabin, gathered the group following after Ella Boole proclaimed to Congress that she represented all women.[14]

The WONPR's argument against Prohibition was its ineffectiveness and how it encouraged disrespect of the law and the Constitution.[14] Bootlegging was common, and once the Great Depression began, many were hoping simply for more jobs and the tax money that would come from legal selling of alcohol again.[15]

Some believed that the WONPR was simply an auxiliary of the AAPA (Association Against the Prohibition Amendment). However, they were independent groups, and differed in opinion on certain matters, such as the WONPR's general endorsement of the Democratic party after they added the wet plank to their platform during the 1932 election.[14]

After their organization, they supported the end of Prohibition through legal and political means. During the Presidential and Congressional campaigns of 1932, they supported those who supported repeal, regardless of which party they belong to. This was despite concerns that the WONPR would simply vote Democrat. For example, in the Senate race in California, the WONPR endorsed the wet Republican over the dry Democrat.[15]

The women in this organization were involved in conventions, met with politicians, and were present and involved in the state ratifying conventions which voted on ratification of the 21st Amendment, putting an end to Prohibition.[15] After the ratification of the 21st Amendment, the WONPR was dissolved.[14]

Molly Pitcher Clubs

There were many anti-Prohibition movements besides the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform. The Association Against the Prohibition Amendment had female chapters they named Molly Pitcher Clubs. This club never gained much national recognition, and likely did not grow very large.[16]

Bootleggers

Most recorded bootleggers were men involved in shady business that had connections to crime lords, but women were typically overlooked in this particular practice. There were many female bootleggers, but only 173 individual cases were recorded. Of those recorded cases, there were certain demographic patterns. Most female bootleggers were mothers who were trying to financially support their families, whether they were widows or not. Mothers usually stayed home to take care of their children and brewing alcohol was not a challenge with privacy and access to kitchens. A majority of female bootleggers were immigrants. They felt more justified in their actions since they had come from various cultures that did not see the creation or consumption of alcohol as an issue.[17]

When arrested for illegal sales of alcohol most women admitted to their actions, but appealed to the judge that their motives were to provide their children with basic necessities. However, there was a high risk of mothers losing custody of their children when they were arrested, even if there was nobody left to care for them while their mother served a jail sentence.[17]

Changes in Social Life

Before Prohibition women generally stayed away from saloons and bars, mostly drinking behind the closed doors of their own homes. During Prohibition, however, women started occupying more public areas such as speakeasies. Breaking rules seemed to appeal to a large population of women and drinking in a public setting was no longer limited to those considered to have low morals.[18]

African American Women

Bootlegging

Out of the 173 cases of recorder female bootleggers, six of them were African American women. It is unknown as to why this ratio is low. African Americans generally opposed Prohibition, but there has been little investigation on their role in bootlegging. They were either majorly unrepresented, or they followed the law despite their general feelings about Prohibition.[17]

Political Views

Most African Americans opposed Prohibition. However, African American women felt that they needed to remain loyal to the Republican party that had put an end to slavery and gave them more rights as citizens. They were torn between their desire for alcohol and their loyalty to a party that supported the Prohibition. They also believed that the Democratic party was using their opposition to Prohibition to attract more African American voters which would eventually lead to the organization of oppression.[19]

Reactions to the Movement

There were mixed reactions to the movement. Some thought that they were pursuing a noble cause, but others believed that Prohibition was a failure and an overreach on the part of the government.

The newspaper Carrie Nation was an editor for in Topeka, Kansas was titled The Smasher’s Mail and published scathing reviews of Nation's actions the first week of February, 1901. Some of those that wrote in claimed that God was in favor of saloons and criticized her for saying she was a follower of God. Others praised her for her actions.[11]

Class Divides

There is controversy over class divides in the support for Prohibition. Some claim that working class-women supported Prohibition because they viewed alcohol as the vice keeping them in poverty. Their husbands would go and drink their money away, leaving them without the money to buy food and other supplies. Others claim that working-class women, along with their husbands, were for repeal because of the new power it gave to police forces to interfere with their lives.[20]

See also

References

- Caswell, John E. (1938). "The Prohibition Movement in Oregon: Part 1, 1836-1904". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 39 (3): 235–261. ISSN 0030-4727. JSTOR 20611128.

- Webb, Holland (1999). "Temperance Movements And Prohibition". International Social Science Review. 74 (1/2): 61–69. ISSN 0278-2308. JSTOR 41882294.

- Bordin, Ruth Birgitta Anderson (1981). Woman and temperance : the quest for power and liberty, 1873-1900. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 9780877221579. OCLC 6649461.

- Blocker, Jack S. (1972). "The Politics of Reform: Populists, Prohibition, and Woman Suffrage, 1891-1892". The Historian. 34 (4): 614–632. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1972.tb00431.x. ISSN 0018-2370. JSTOR 24442960.

- Ivy, James D. (1998). ""The Lone Star State Surrenders to a Lone Woman": Frances Willard's Forgotten 1882 Texas Temperance Tour". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 102 (1): 44–61. ISSN 0038-478X. JSTOR 30239154.

- Kreider, Marie L.; Wells, Michael R. (1999). "White Ribbon Women: The Women's Christian Temperance Movement in Riverside, California". Southern California Quarterly. 81 (1): 117–134. doi:10.2307/41171932. JSTOR 41171932.

- "Annie Turner Wittenmyer | American relief worker and reformer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- "Frances Willard | American educator". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- "Carry Nation | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- Grace, Fran (2001). Carrie A. Nation: Retelling the Life. University of Indiana: Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 283–361. ISBN 978-0253338464.

- Nation, Carrie (2011-05-17). "Smasher's Mail, Vol. 1, No. 6, 1901". Smasher's Mail Newspaper Collection.

- "Anna Adams Gordon | American social reformer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- Kyvig, David E. (1976). "Women Against Prohibition". American Quarterly. 28 (4): 465–482. doi:10.2307/2712541. JSTOR 2712541.

- Neumann, Caryn E. (1997). "The End of Gender Solidarity: The History of the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform in the United States, 1929-1933". Journal of Women's History. 9 (2): 31–51. doi:10.1353/jowh.2010.0564. ISSN 1527-2036.

- Root, Grace C. (1934). "Women and Repeal: The Story of the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform". New York: Harper & Bros.

- Rose, Kenneth D. (1997). American women and the repeal of prohibition. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0814774663. OCLC 60179596.

- Sanchez, Tanya Marie (2000). "The Feminine Side of Bootlegging". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 41 (4): 403–433. ISSN 0024-6816. JSTOR 4233697.

- Murphy, Mary (1994). "Bootlegging Mothers and Drinking Daughters: Gender and Prohibition in Butte, Montana". American Quarterly. 46 (2): 174–194. doi:10.2307/2713337. JSTOR 2713337.

- Materson, Lisa C. (2009). "African American Women, Prohibition, and the 1928 Presidential Election". Journal of Women's History. 21 (1): 63–86. doi:10.1353/jowh.0.0059. ISSN 1527-2036.

- Willrich, Michael (July 2003). ""Close that Place of Hell": Poor Women and the Cultural Politics of Prohibition". Journal of Urban History. 29 (5): 555–574. doi:10.1177/0096144203029005003. ISSN 0096-1442.