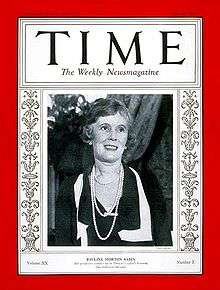

Pauline Sabin

Pauline Morton Sabin (April 23, 1887 - December 28, 1955) was a prohibition repeal leader and Republican party official. She was born in Chicago, Illinois and she was a New Yorker who founded the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR). Sabin was very active in politics and known for her social status and charismatic personality. Sabin's efforts were a significant factor in the repeal of Prohibition.[1]

Time Magazine

July 18, 1932

Early life

Pauline Sabin was a wealthy, elegant, socially prominent, and politically well-connected New Yorker. She was born Pauline Joy Morton, the daughter of Paul Morton and Charlotte Goodridge. Sabin's family was very active in business and politics. Her father Paul Morton was a railroad executive. Her uncle Joy Morton founded Morton Salt Company. Her grandfather Julius Sterling Morton had been a prominent Nebraska Democrat who served as Secretary of Agriculture under President Grover Cleveland, and her father had served as Secretary of the Navy to President Theodore Roosevelt. This later on helped spark her interest in politics.[2] Sabin's education included private schooling; she attended school in Chicago and Washington before making her debut into society.[1]

She married J. Hopkins Smith, Jr., in 1907. The couple had two sons before divorcing in 1914.[3] After getting divorced, she owned her own interior decorating business.[1] In 1916 she married Charles H. Sabin, president of the Guaranty Trust Company[4] and treasurer of the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment (AAPA). Despite the fact that her husband was a Democrat, Sabin remained a Republican but did not support Coolidge when he refused to back repeal of the 18th Amendment. She was very active in politics; she became the first member of the Suffolk County Republican Committee in 1919. She later on helped find the Women's National Republican Club and became the president. From 1921-1926 she gained enormous recognition for recruiting thousands of members and for raising funds. She also was selected to be New York's first woman representative on the Republican National Committee in 1923.[1]

Before 1929, she favored small government and free markets. She initially supported prohibition, as she later explained: "I felt I should approve of it because it would help my two sons. The word-pictures of the agitators carried me away. I thought a world without liquor would be a beautiful world." Towards the 1920s, however, Sabin realized that no one was taking Prohibition seriously.[1] She was growing increasingly disenchanted with prohibition but worked on behalf of Herbert Hoover in the election of 1928 despite his uncertain stand on the issue. In his inauguration speech he vowed to enforce anti-liquor legislation. After the enactment of the Jones-Stalker Act in May 1929 drastically increased penalties for the violation of prohibition, she resigned from the Republican National Committee and took up the cause of repealing prohibition.

Opposition to prohibition

Sabin voiced her first cautious public criticism of prohibition in 1926.[5] By 1928 she had become more outspoken. The hypocrisy of politicians who would support resolutions for stricter enforcement and half an hour later be drinking cocktails disturbed her. The ineffectiveness of the law, the apparent decline of temperate drinking, and the growing prestige of bootleggers troubled her even more. Mothers, she explained, had believed that prohibition would eliminate the temptation of drinking from their children's lives but found instead that "children are growing up with a total lack of respect for the Constitution and for the law."

After her resignation as Republican National committeewoman, Sabin received tremendous support.[1] In May 1929 in Chicago, Pauline Sabin founded the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform with two dozen of her society friends as its nucleus. Its leadership was dominated by wives of American industry leaders. She found women who would be active workers. The organization had outstanding women as their leaders: Mrs. R. Stuyvesant Pierrepont, Mrs. Pierre S. du Pont, and Mrs. Coffin Van Rensselaer.[1] The WONPR had very prominent family names, they were not only highly involved with their community but they were also very wealthy.[2] The Women of the WONPR were considered smart and sophisticated women of the era.[2] Their high social status attracted press coverage and made the movement fashionable. For housewives throughout middle America, joining the WONPR was an opportunity to mingle with high society. In less than two years, membership grew to almost 1.5 million,this was triple of the membership of the WCTU.[1] Sabin became a symbol for independent women; she showed women that they weren't bound to support the Prohibition movement.[2]

As head of the WONPR, she countered the arguments of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). She later recalled that she decided to fight Prohibition while sitting in a congressional office where the president of the WCTU asserted: "I represent the women of America!" Repeal would protect families from the crime, corruption, and furtive drinking that prohibition had created. Repeal would return decisions about alcohol to families. The WONPR stole tactics and members as well as arguments from the WCTU. Its members looked for allies in both major parties and minimized internal dissension. The WONPR gained the upper hand in the battle for the support from women; the WONPR became the largest repeal group in the country.[2] Sabin thought that it was her duty as chairwoman to make sure the cause was made public. In 1923, WONPR moved the campaign southward to places like South Carolina and Charleston to appeal for southern support. Sabin went to Atlanta where she was the subject of the social page of the Atlanta Constitution and later on her picture appeared on the cover of Time magazine.[1] The WONPR gained massive recognition from the media; they wanted daring, newsworthy women.[2]

In later statements, she elaborated further on her objections to prohibition. With settlement workers reporting increasing drunkenness, she worried, "The young see the law broken at home and upon the street. Can we expect them to be lawful?" Mrs. Sabin complained to the House Judiciary Committee: "In pre-prohibition days, mothers had little fear in regard to the saloon as far as their children were concerned. A saloon-keeper's license was revoked if he were caught selling liquor to minors. Today in any speakeasy in the United States you can find boys and girls in their teens drinking liquor, and this situation has become so acute that the mothers of the country feel something must be done to protect their children."

After repeal

After the repeal amendment in December 1933, the WONPR dissolved immediately. She returned to politics and joined the American Liberty League, formed by conservative Democrats in 1934. This organization was formed to oppose Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. She hoped that women would show the same enthusiasm for the league like the WONPR but they didn't. Due to the lack of membership, the committee only lasted a year but she still remained on the executive committee in the 1930s. By 1933 she was widowed and remarried in 1936 to Dwight F. Davis. He was former secretary of war and donor of the Davis Cup tennis trophy. She campaigned for Fiorello La Guardia and Alfred Landon in 1936. In 1940, Sabin became the director of Volunteer Special Services for the American Red Cross. She aided more than 4 million families. In 1943, she resigned and moved to Washington D.C. She became a consultant on the White House interior decoration renovation for President Harry Truman. On December 27, 1955 Pauline Sabin died in Washington D.C.[1]

Notes

- Marilyn Elizabeth Perry. "Sabin, Pauline Morton"; http://www.anb.org/articles/06/06-00142.html; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

- Lerner, Michael A. Dry Manhattan: Prohibition in New York City 2007, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- New York Times: "Mrs. Charles H. Sabln Will Be Wed in May To Dwight Davis, Former Secretary of War," April 8, 1936, accessed May 29, 2011

- New York Times: "Dwight Davis Dies," November 29, 1945, accessed May 29, 2011

- The Independent Review: Paula Baker, "Review: Kenneth D. Rose, American Women and the Repeal of Prohibition, Fall 1998, accessed November 28, 2010

Sources

- David E. Kyvig, "Pauline Sabin" in Dictionary of American Biography, (Supplement 5, volume 5) (Chicago: Charles Scribner's Sons/Thompson Gale, 1977)

- David E. Kyvig, "Pauline Morton Sabin" in Notable American Women: The Modern Period, edited by Barbara Sicherman and Carol Hurd Green (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980)

- David E. Kyvig, Daily Life in the United States, 1920-1940: How Americans Lived Through the Roaring Twenties and the Great Depression (Ivan R. Dee, 2004)

- David E. Kyvig, "Hard Times, Hopeful Times" in Repealing National Prohibition (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1979)

- David E. Kyvig, ed., Law, Alcohol, and Order: Perspectives on National Prohibition (Greenwood Press, 1985)

- Catherine G. Murdock, Domesticating Drink: Women, Men, and Alcohol, 1870-1940 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998)

- Daniel Okrent, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (NY: Scribner, 2010)

- Kenneth D. Rose, American Women and the Repeal of Prohibition (NY: New York University Press, 1997)

- Perry, Marilyn E. "American National Biography Online." American National Biography Online. American National Biography, Feb. 2000. Web. 02 Oct. 2013.

- "Pauline Sabin." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Aug. 2013. Web. 02 Oct. 2013.

- Lerner, Michael A. Dry Manhattan: Prohibition in New York City. Cambridge, MA:Harvard UP, 2007. Print.

- Marilyn Elizabeth Perry. "Sabin, Pauline Morton"; http://www.anb.org/articles/06/06-00142.html; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

External links

- Bayberry Land Biography: Pauline Morton Smith Sabin Davis

- Hamptons.Com: Bayberry Land, by Mary Cummings