Wivenhoe, Narellan

Wivenhoe is an historic house built in 1837 at Narellan, near Camden, in New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by the Sydney architect John Verge who also designed Camden Park and Elizabeth Bay House. The house has had some very notable residents.

| Wivenhoe | |

|---|---|

Wivenhoe, c. 1900 | |

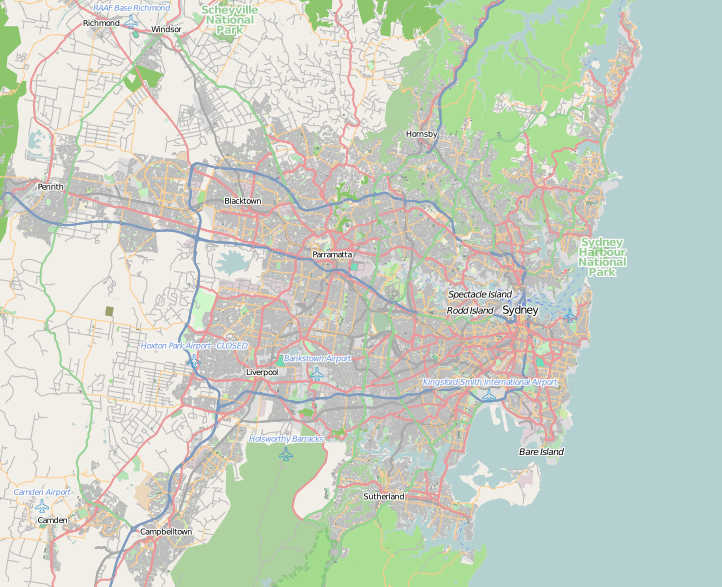

Location in greater Sydney | |

| Etymology | Wivenhoe, Essex |

| General information | |

| Status | Complete |

| Type |

|

| Location | Narellan, near Camden, New South Wales |

| Country | Australia |

| Coordinates | 34°01′30″S 150°41′52″E |

| Client | Charles and Eliza Cowper |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | John Verge |

The building is now used as Mater Dei Special School, an inclusive school for children with intellectual disabilities, and is administered by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Wollongong. The building is open for inspection by the public.

House

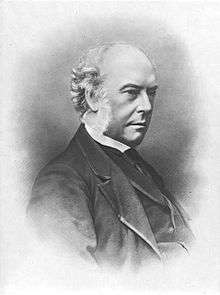

Sir Charles and Lady Eliza Cowper

Charles Cowper built Wivenhoe in 1837 and lived there for about 30 years. During his residence at Wivenhoe he served as Premier of New South Wales five times between 1856 and 1870.

Cowper was born in 1807 in Lancashire in England and was the third son of William Cowper and Hannah Horner who migrated to New South Wales when Charles was only two years old. His father was assistant colonial chaplain. Charles was educated privately and at the age of 18 he entered the Commissariat Department of the Government of New South Wales.[1]

In 1831 he married Eliza Sutton daughter of Daniel Sutton who lived in the village of Wivenhoe in Essex.[2]:8 The couple had six children, two sons and four daughters.[3] In 1836 Cowper began building Wivenhoe at Camden on land that had originally been granted by the Governor of New South Wales, Lachlan Macquarie, to his father.[2]:8

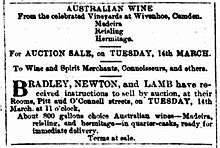

Soon after the house was built the Cowpers planted a vineyard which was one of the earliest in the colony.[4] By 1850 the Wivenhoe wines were becoming celebrated with several very favourable mentions in the newspapers.[5] In 1856 one newspaper described the wines that were produced there. These were Muscat, Riesling and red wine which they said was similar to Rhine Valley wines and Madeira which they thought was like Frontenac.[6] In 1858 Conrad Martens sketched of the house. In 1866 Wivenhoe was advertised for sale and the property was described in the following terms:[7]

This commodious family mansion contains the following accommodation. On the ground floor a spacious hall 9 feet wide entered from a tastefully designed portico. There is also a drawing room, dining room, breakfast room, library, butler’s pantry, store and a range of domestic offices such as kitchen, laundry, ironing room, scullery and servant’s room. On the upper floor there are six bedrooms. On the basement are the celebrated Wivenhoe Wine cellars extending under the whole of the main building. The cellars are of immense strength and thickness 9 feet in height and were especially built for their present use being capable of storing a very large quantity of wine.

— The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 November 1864.

In 1870 Cowper became Agent-General for NSW which was a position situated in London. He and Eliza sailed for England with their youngest daughter, Rose, early in 1871.[2]:158 Charles Cowper's health deteriorated over the next few years and in 1875 he died in Kensington, London.[1] Lady Cowper and Rose returned to Sydney and both resided at Bowral for many years. Lady Cowper died in 1884 and was buried at St Paul's Church near Wivenhoe.[8]

Henry and Caroline Thomas

Henry Arding Thomas was born in 1819 in India. His father was Robert Arding Thomas, a Major in the British Army, who served in India. His mother was Caroline Gilbert. In 1856 Henry married Caroline Frances Husband in Sydney.[9] Caroline was born in Devon, England, in 1833. After their marriage the couple went to live in Armidale on a property called Saumarez and had a family of five boys and six girls.[9] While he was in Armidale, Thomas was a local magistrate, foundation president of the pastoral and Agricultural Society and involved with Anglican Church affairs.[10] In 1874 Henry sold Saumarez and the following year he bought Wivenhoe. In 1876 an advertisement appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald for some of the wines that were produced from the Wivenhoe Vineyard. Henry died in 1884 and his widow, Caroline continued to live at Wivenhoe until her death in 1903.

Walter Watt and Muriel Watt

Walter Oswald Watt was born in 1878 in Bournemouth, England. His father was John Brown Watt, a merchant and a Member of the New South Wales Legislative Council,[11] and his mother was Mary Jane Watt (née Holden), who died when he was a baby. Walter Watt spent the first ten years of his life in Sydney and was sent then to be educated in England at Clifton College, Bristol, and Trinity College, Cambridge where he obtained his Bachelor and Master of Arts degrees. Watt returned to Sydney in 1900 and became second lieutenant in the New South Wales Scottish Rifles and in 1902 was appointed aide-de-camp to the Governor of New South Wales.[12]

In 1902 Watt married Muriel Maud Williams, the daughter of Sir Hartley Williams, a Justice of the Supreme Court of Victoria,[13] and Edith Ellen Williams (née Horne). The couple bought Wivenhoe in 1905 and in the same year had their only child, James. They owned the property until 1910 when they sold it to the Sisters of the Good Samaritan.

In 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, Walter joined the French Foreign Legion and was awarded two military honours. In 1916 he transferred to the newly formed Australian Flying Corps and served there as captain.

Orphanage and school

When the Sisters of the Good Samaritan bought Wivenhoe in 1910 they made it an orphanage for the disadvantaged children in the inner city areas of Sydney. The house became part of Mater Dei, an organisation that was established by the Good Samaritan Sisters. In 1957 the Mater Dei Special School commenced using Wivenhoe as a school for children with intellectual disabilities and still serves this function today.

See also

References

- Ward, John M. (1969). "Cowper, Sir Charles (1807–1875)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Powell, Alan (1977). Patrician democrat: the political life of Charles Cowper, 1843-1870. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84132-9.

- NSW Births Deaths and Marriages between 1834 and 1844

- "Mater Dei Vineyard". Mater Dei Camden.

- "CAMDEN". The Sydney Morning Herald. 26 January 1850. p. 3 (Supplement to Sydney Morning Herald). Retrieved 20 June 2020 – via Trove, National Library of Australia.

- "AUSTRALIAN WINES". The Maitland Mercury And Hunter River General Advertiser. New South Wales, Australia. 11 December 1856. p. 3. Retrieved 20 June 2020 – via Trove, National Library of Australia.

- "Advertising". The Sydney Morning Herald. 18 November 1864. p. 7. Retrieved 20 June 2020 – via Trove, National Library of Australia.

- "THE LATE LADY COWPER". Queanbeyan Age. New South Wales, Australia. 5 February 1884. p. 2. Retrieved 20 June 2020 – via Trove, National Library of Australia.

- NSW Births Deaths and Marriages

- "Saumarez Homestead". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Walsh, G. P. (1976). "Watt, John Brown (1826–1897)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Johnston, Susan (1990). "Watt, Walter Oswald (1878–1921)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Miller, Robert (1976). "Williams, Sir Hartley (1843–1929)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

External links

- "About: Our history". Mater Dei. 2020.