Wingsuit flying

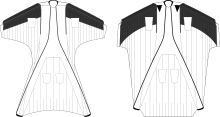

Wingsuit flying (or wingsuiting) is the sport of flying through the air using a wingsuit which adds surface area to the human body to enable a significant increase in lift. The modern wingsuit, first developed in the late 1990s, creates a surface area with fabric between the legs and under the arms. Wingsuits are sometimes referred to as "birdman suits" (after the makers of the first commercial wingsuit), "squirrel suits" (from their resemblance to flying squirrels' wing membrane), and "bat suits" (due to their resemblance to the animal or perhaps the superhero).

.jpg)

A wingsuit flight normally ends by deploying a parachute, and so a wingsuit can be flown from any point that provides sufficient altitude for flight and parachute deployment — normally a skydiving drop aircraft, or BASE-jump exit point such as a tall cliff or a safe mountain top. The wingsuit flier wears parachute equipment specially designed for skydiving or BASE jumping. While the parachute flight is normal, the canopy pilot typically unzips arm wings (after deployment) to be able to reach the steering parachute toggles and control the descent path.

History

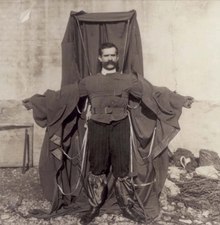

An early attempt at wingsuit flying was made on 4 February 1912 by a 33-year-old tailor, Franz Reichelt, who jumped from the Eiffel Tower to test his invention of a combination of parachute and wing, which was similar to modern wingsuits. He misled the guards by saying that the experiment was going to be conducted with a dummy. He hesitated quite a long time before he jumped, and was killed when he hit the ground head first, opening a measurable hole in the frozen ground.[1]

A wingsuit was first used in the US in 1930 by a 19-year-old American, Rex G Finney of Los Angeles, California, as an attempt to increase horizontal movement and maneuverability during a parachute jump.[2][3] These early wingsuits were made of materials such as canvas, wood, silk, steel, and whalebone. They were not very reliable, although some "birdmen", notably Clem Sohn and Leo Valentin, claimed to have glided for miles.

In the mid-1990s, the modern wingsuit was developed by Patrick de Gayardon of France, adapted from the model used by John Carta. In 1997, the Bulgarian Sammy Popov designed and built a wingsuit that had a larger wing between the legs and longer wings on the arms. His prototype was developed at Boulder City, Nevada. Testing was conducted in a vertical wind tunnel in Las Vegas at Flyaway Las Vegas. Popov's wingsuit first flew in October 1998 over Jean, Nevada, but it never went into commercial production. In 1998, Chuck "Da Kine" Raggs built a version that incorporated hard ribs inside the wing airfoils. Although these more rigid wings were better able to keep their shape in flight, this made the wingsuit heavier and more difficult to fly. Raggs' design also never went into commercial production. Flying together for the first time, Popov and Raggs showcased their designs side by side at the World Free-fall Convention at Quincy, Illinois, in August 1999. Both designs performed well. At the same event, multiple-formation wingsuit skydives were made which included de Gayardon's, Popov's, and Raggs' suits.

Commercial era

In 1999, Jari Kuosma of Finland and Robert Pečnik of Croatia teamed up to create a wingsuit that was safe and accessible to all skydivers. Kuosma established Bird-Man International Ltd. the same year. BirdMan's "Classic", designed by Pečnik, was the first wingsuit offered to the general skydiving public. BirdMan was the first manufacturer to advocate the safe use of wingsuits by creating an instructor program. Created by Kuosma, the instructor program's aim was to remove the stigma that wingsuits were dangerous and to provide wingsuit beginners (generally, skydivers with a minimum of 200 jumps) with a way to safely enjoy what was once considered the most dangerous feat in the skydiving world. With the help of Birdman instructors Scott Campos, Chuck Blue, and Kim Griffin, a standardized program of instruction was developed that prepared instructors.[4] Wingsuit manufacturers Squirrel Wingsuits, TonySuits Wingsuits, Phoenix-Fly, Fly Your Body, and Nitro Rigging have also instituted coach training programs.

Technique

Launch

The wingsuit flier enters free fall wearing both a wingsuit and parachute equipment. Exiting an aircraft in a wingsuit requires skilled techniques that differ depending on the location and size of the aircraft door. These techniques include the orientation relative to the aircraft and the airflow while exiting, and the way in which fliers spread their legs and arms at the proper time so as not to hit the aircraft or become unstable. The wingsuit immediately starts to fly upon exiting the aircraft in the relative wind generated by the forward speed of the aircraft. Exiting from a BASE jumping site, such as a cliff, or exiting from a helicopter, a paraglider, or a hot air balloon, is fundamentally different from exiting a moving aircraft, as the initial airspeed upon exit is absent. In these situations, a vertical drop using the forces of gravity to accelerate is required to generate the airspeed that wingsuits need to generate lift.

.jpg)

Glide

A wingsuit modifies the body area exposed to wind to increase the desired amount of lift with respect to drag generated by the body. With training, wingsuit pilots can achieve sustained glide ratio of 2.5:1 or more.[5] This means that for every meter dropped, two and a half meters are gained moving forward. With body shape manipulation and by choosing the design characteristics of the wingsuit, fliers can alter both their forward speed and fall rate. The pilot manipulates these flight characteristics by changing the shape of the torso, de-arching and rolling the shoulders and moving hips and knees, and by changing the angle of attack in which the wingsuit flies in the relative wind, and by the amount of tension applied to the fabric wings of the suit. The absence of a vertical stabilizing surface results in little damping around the yaw axis, so poor flying technique can result in a spin that requires active effort on the part of the skydiver to stop.

A typical skydiver's terminal velocity in belly to earth orientation ranges from 180–225 km/h (110 to 140 mph). A wingsuit can reduce these speeds dramatically. A vertical instantaneous velocity of 40 km/h (25 mph) has been recorded. However the speed at which the body advances forward through the air is still much higher (up to 100 km/h [62 mph]).

Deployment

At a planned altitude above the ground in which a skydiver or BASE jumper typically deploys the parachute, wingsuit fliers will also deploy their parachutes. Deployment is typically initiated by reaching back and throwing a pilot chute. The parachute is flown to a controlled landing at the desired landing spot using typical skydiving or BASE jumping techniques.

Record-keeping

Wingsuit pilots often use tools including portable GPS receivers to record their flight path. This data can be analyzed later to evaluate flight performance in terms of fall rate, speed, and glide ratio. When jumping for the first time at a new location, BASE jumpers will often evaluate terrain using maps and laser range finders. By comparing a known terrain profile with previously recorded flight data, jumpers can objectively evaluate whether a particular jump is possible.[6] BASE jumpers also use landmarks, along with recorded video of their flight, to determine their performance relative to previous flights and the flights of other BASE jumpers at the same site.

Suit design

Modern wingsuits use a combination of materials in order to create an airfoil shape. The main surface is typically made from ripstop nylon, with various materials used to reinforce the leading edge, and reduce drag.[7]

- The tri-wing wingsuit has three individual ram-air wings attached under the arms and between the legs.

- The mono-wing wingsuit design incorporates the whole suit into one large wing.

Having a smooth leading edge is especially important as it is the source of most lift and most drag. Reducing inlet drag while maintaining high internal suit pressure is also important in modern wingsuit design.

Wingsuit BASE

As compared to skydiving from an airplane, BASE jumping involves jumping from a "fixed object" such as a cliff. BASE jumping in its modern form has existed since at least 1978, but it was not until 1997 that Patrick de Gayardon made some of the first ever wingsuit BASE jumps combining the two disciplines.[8] Compared to normal BASE jumping, wingsuit BASE jumping allows pilots to fly far away from the cliffs they jumped from, and drastically increase their freefall time before deploying a parachute. Since 2003, many BASE jumpers have started using wingsuits, giving birth to wingsuit BASE.[9]

The wingsuit flier jumps from a cliff, and within a split second, an intake fills the suit's baffled chambers with air, turning them rigid. By holding a proper body position, the wingsuit flier is able to glide forward at a ratio of 3:1, meaning that they are moving forward three feet for every foot of descent (or 3 meters for every meter of descent).[10]

As suit technology and pilot skill have improved, wingsuit BASE jumpers have learned to control their flight so that they can fly just meters away from terrain. The practice of flying a wingsuit close to the faces and ridges of mountains is called proximity flying. By flying near terrain, wingsuit pilots feel a greater sense of speed due to having a close visual reference. Loic Jean-Albert of France is one of the first proximity flyers, and his pioneering flying brought many BASE jumpers into the sport.[11] In November 2012, Alexander Polli became the first wingsuit BASE jumper to successfully strike a wingsuit target.[12]

Wingsuit BASE jumping carries additional risk beyond a wingsuit skydive. Jumping from a fixed object means starting with low airspeed which requires different flying positions and skills. During the flight, hazards exists such as trees, rocks and the ground which must be avoided. While skydivers typically carry two parachutes, a main and a reserve, wingsuit BASE jumpers typically only carry one BASE-specific parachute.

Wingsuit BASE jumping is unregulated, but to perform the activity safely requires jumpers to be an experienced skydiver, wingsuit pilot, and BASE jumper. It takes hundreds of practice jumps to achieve proficiency in each of these disciplines before considering wingsuit BASE.

Further technical developments

Jet-powered wingsuits

As of 2010, there have been experimental powered wingsuits, often using small jet engines strapped to the feet[13] or a wingpack setup to allow for even greater horizontal speeds and even vertical ascent.

On 25 October 2009, in Lahti, Finland, Visa Parviainen jumped from a hot air balloon in a wingsuit with two small turbojet engines attached to his feet. The engines provided approximately 160 N (16 kgf, 35 lbf) of thrust each and ran on JET A-1 fuel. Parviainen achieved approximately 30 seconds of horizontal flight with no noticeable loss of altitude.[13][14] Parviainen continued jumping from hot air balloons and helicopters, including one for the Stunt Junkies program on Discovery Channel.[15]

Christian Stadler from Germany invented the "VegaV3 wingsuit system" that uses an electronic adjustable hydrogen peroxide rocket.[16] The rocket provides 1000 Newtons (100 kgf) of thrust and produces no flames or poisonous fumes. His first successful powered wingsuit jump was in 2007, when he reached horizontal speeds of over 255 km/h (160 mph).[17]

Wingpack

Another variation on which studies are being focused is the wingpack, which consists of a strap-on rigid wing made of carbon fibre.[18]

Training

Flying a wingsuit can add considerable complexity to a skydive. So, according to the Skydivers' Information Manual, the United States Parachute Association requires that any jumper have a minimum of 200 freefall skydives before completing a wingsuit first jump course and making a wingsuit jump.[19] Requirements in other nations are similar. Wingsuit manufacturers offer training courses and certify instructors, and also impose the minimum jump numbers required before purchasing a wingsuit. Typically wingsuit pilots will start on a smaller wingsuit with less surface area. With practice, pilots can learn to fly larger suits with more surface area, which allow for increased glide and airtime.

Records

Wingsuit formation records

Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), the world governing airsports body, established judging criteria for official world record wingsuit formations in February 2015. The rules are available on the FAI website.[lower-alpha 1]

Prior to this, the largest wingsuit formation recognized as meeting the criteria for a national record consisted of 68 wingsuit pilots, which set a U.S. national record at Lake Elsinore, California, on 12 November 2009.[20] The largest global record was a diamond formation involving 100 wingsuit pilots at Perris, California, on 22 September 2012.[21] These records have since been retired as they do not meet the current rules.[lower-alpha 1]

Two World Records have been set since the rules update. A 42-person formation over Moorsele, Belgium, set an FAI record on 18 June 2015. This was broken on 17 October 2015, when 61 wingsuit pilots set the current FAI world record over Perris Valley Airport near Perris, California.[22][23]

The current U.S. national record includes 43 wingsuit pilots. It was set on 5 October 2018 in Rosharon, Texas at Skydive Spaceland-Houston.[lower-alpha 2]

Wingsuit BASE jump records

- Highest

On 23 May 2006, the Australian couple Heather Swan and Glenn Singleman jumped from 6,604 metres (21,667 ft) off Meru Peak in India, setting a world record for highest wingsuit BASE jump.[24] This record was broken on 5 May 2013, by the Russian Valery Rozov, who jumped from 7,220 metres (23,690 ft) on Mount Everest's North Col.[25] Rozov broke his own record by jumping from 7,700 metres (25,300 ft) on Cho Oyu in 2016.[26]

- Longest

The longest verified wingsuit BASE jump is 7.5 kilometres (4.7 mi) by the American Dean Potter[27] on 2 November 2011. Potter jumped from the Eiger mountain and spent 3 minutes and 20 seconds in flight, descending 2,800 metres (9,200 ft) of altitude.

- Biggest

The biggest wingsuit BASE jump as measured from exit to landing was performed on 11 August 2013 by Patrick Kerber with a height of 3,240 metres (10,630 ft) off the Jungfrau in Switzerland.[28]

Wingsuit flight records

- Fastest

On 22 May 2017, British wingsuit pilot Fraser Corsan set world records for the fastest speed reached in a wingsuit of 396.86 km/h (246.60 mph).[29]

- Greatest average horizontal speed

The current world record for greatest average horizontal speed within the performance competition rules, i.e. within 1,000 m (3,300 ft) of vertical distance, was set by Travis Mickle (USA) with a speed of 325.4 km/hr (202.19 mph) 6 November 2017.[30]

- Longest time and highest altitude

On 20 and 21 April 2012, Colombian skydiver Jhonathan Florez set Guinness World Records in wingsuit flying. The jumps took place in La Guajira in Colombia for the following records:

- Longest time: The longest (duration) wingsuit flight was 9 minutes, 6 seconds[31]

- Highest: The highest altitude wingsuit jump was 11,358 m (37,265 ft)[32]

The current world record for longest time in flight within the performance competition rules, i.e. within 1,000 m (3,300 ft) of vertical distance, was set on 28 Aug 2018 by Chris Geiler (USA) with a time of 100.2 sec (1.67 min)[33]

- Farthest

The current Guinness World Record for "greatest absolute distance flown in a wing suit" is 32.094 km (19.94 mi) set by Kyle Lobpries (USA) in Davis, CA 30 May 2016.[34]

The current world record for longest horizontal distance covered within the performance competition rules, i.e. within 1,000 m (3,300 ft) of vertical distance, was set on 27 May 2017 by U.S. wingsuit pilot Alexey Galda with a distance of 5.137 km (3.19 mi)[35]

- Landing

On 23 May 2012, British stuntman Gary Connery safely landed a wingsuit without deploying his parachute, landing on a crushable "runway" (landing zone) built with thousands of cardboard boxes.[36]

Safety

Wingsuit flying is dangerous, and the pursuit of it has contributed to a number of notable fatalities since its inception. Despite training and regulation, wingsuit BASE jumping remains a precarious pastime. A 2012 University of Colorado study found that for wingsuit BASE jumping there was approximately one severe injury for every 500 jumps undertaken.[37]

In popular culture

Wingsuits were showcased in the 1969 film, The Gypsy Moths, starring Burt Lancaster and Gene Hackman.[38]

In Lara Croft: Tomb Raider – The Cradle of Life, Lara (Angelina Jolie) and Terry (Gerard Butler) escape by wingsuiting off a skyscraper.

In the 2015 remake of Point Break the protagonist goes wingsuit flying with a group of criminals in order to gain their trust. The sequence was shot in Walenstadt, Switzerland.[39]

Notes

- The rules are available under the Wingsuit tab on the FAI website section for parachuting: http://www.fai.org/ipc-documents

- The U.S. national wingsuit formation record can be found in the official USPA records database with the status set to "current," the zone set to "U.S. National," and the group set to "Wingsuit Flying". http://competition.uspa.org/records/current

Citations

- "Chute mortelle d'un inventeur de parachute" [Deadly fall of a parachute inventor]. Le Temps (in French). Paris, FR. 6 February 1912. p. 4. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- "Human flying squirrel zooms through air". Popular Science Monthly. September 1930. p. 53.

- Ewers, Retta E. (January 1934). "Rex - The Human Glider". Popular Aviation (aka Flying Magazine). p. 28.

- "Bird-man worldwide instructors list". Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- "TonySuit Wingsuits - Dean Potter, record wingsuit flight - November 2011". Tony Suit Inc. 2 November 2011. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012.

After checking out our GPS and Goggle Earth we concluded that I flew a new longest wingsuit BASE-jump to date. My flight was 9,200 feet vertical, 7.5 kilometers horizontal and approximately 3 minutes 20 seconds of flight time before opening my parachute.

- "Pilot pioneers harrowing, low-level wingsuit flights". National Geographic. May 2015.

- "Squirrel Aura Wingsuit". Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- "Wingsuit History". FlyLikeBrick.

- Gerdes, Matt (2010). The Great Book of BASE. BirdBrain Publishing. p. 216.

- "Why are so many BASE jumpers dying?". National Geographic. 30 August 2016.

- "A Life in Flight: Wingsuit pioneer Loic Jean-Albert, "The Flying Dude"". Adventure Sports Journal. 2 April 2012.

- "Alexander Polli shatters a foam target while flying in a wingsuit". Outside Online. 26 November 2012.

- "First jet powered Birdman flight". Dropzone.com. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- Skydiving with rocket engines (video). Engineering.com.

Original video of Visa's first jump.

- Animation of Visa's helicopter jump. TDMA Animation Studio website (animation). Stunt Junkies show. Discovery channel.

- "First living rocket airplane in the world!". News. Peroxide Propulsion. 3 January 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "First living rocket plane in the world". YouTube. 29 September 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "A Modern-day Lilienthal: Alban Geissler constructs wings for people without nerves". SPELCO GbR. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- "Skydivers' Information Manual" (PDF). USPA. Section 6-9, page 143. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- "USPA Records: largest wingsuit formation jump". Uspa.org. 1 May 2006. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "Largest wingsuit formation". The Daily Telegraph. London. 22 September 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- "61 Wingsuit divers set formation record". discovery.com. 21 October 2015.

- "FAI Largest Formation Records - Wingsuit Flying no Grip", FAI Record File, 17 October 2015, retrieved 23 May 2017

- "Leap from the top of the world". Sydney Morning Herald. 8 June 2006. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- Cooper, Tarquin (28 May 2013). "Valery Rozov BASE jumps from Mt. Everest". Red Bull.

- "Rozov BASE jumped Cho Oyu". ExplorersWeb. 25 October 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- "Dean Potters record breaking flight from the Eiger". Archived from the original on 22 April 2012.

- "Patrick Kerber sets an altitude distance record with a wingsuit BASE jump off the Jungfrau". Red Bull. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- "Fastest speed reached in a wing suit". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- "World Air Sports Federation". fai.org. Records. Page 2. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Longest (duration) wingsuit flight". Guinness World Records.

- "Highest altitude wingsuit jump". Guinness World Records.

- "World Air Sports Federation". Records. fai.org. Page 2. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Greatest absolute distance flown in a wingsuit". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Records Database". uspa.org. Competition Records. United States Parachute Association. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Stuntman Gary Connery completes 2,400 ft skydive without a parachute". Telegraph. London, UK.

- Mei-Den, Omer (2012). "The epidemiology of severe and catastrophic injuries in BASE jumping". Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 22 (3): 262–267. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e31824bd53a. PMID 22450590.

- "A Brief History of Wingsuiting". World Wingsuit League. 20 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- "Point Break Trivia". IMDB.

- Abrams, Michael (2006). Birdmen, Batmen, and Skyflyers: Wingsuits and the Pioneers who Flew in Them, Fell in Them, and Perfected Them. ISBN 1-4000-5491-5.

- Gerdes, Matt (2010). The Great Book of BASE. BirdBrain Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4000-5491-6.

- Campos, Scott (2005). Skyflying Wingsuits in Motion.

Further reading

- Dixon, Donna (16 April 2010). "Soldier sets wing-suit world record". U.S. Army. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "Wingsuit flyer dives through hole in Chinese mountain". BBC News. 26 September 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

Brief article with video

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wingsuit flying. |

- "Wingsuit Skydiving".

The history of wingsuits, their evolution and how to get started

- "How to start wingsuit flying".

Prices, where to learn, videos, risks & news

- "How do I learn how to wing-suit?". Adventures in Skydiving.

- "Acrobatic Wingsuit Team". FlyLikeBrick.