Willis Polk

Willis Jefferson Polk (October 3, 1867 – September 10, 1924) was an American architect best known for his work in San Francisco, California. For ten years, he was the West Coast representative of D.H. Burnham & Company. In 1915, Polk oversaw the architectural committee for the Panama–Pacific International Exposition (PPIE).

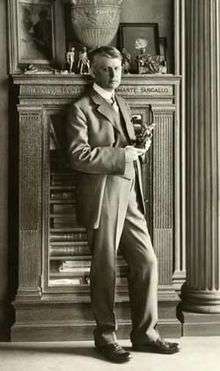

Willis Polk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Willis Jefferson Polk October 3, 1867 Jacksonville, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | September 10, 1924 (aged 56) San Mateo, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Santa Clara Mission Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Architect |

Early life and education

He was born October 3, 1867 in Jacksonville, Illinois to carpenter Willis Webb Polk (1836-1906).[1] He was the eldest of five children, in 1873 the family moved to Saint Louis, Missouri and again by 1881 to Hope, Arkansas.[1] He began his architectural training when he was eight years old in a local contractor's office. He worked in his father's carpenter shop in St. Louis, Missouri as he was growing up.[1]

In 1887, Polk moved to Kansas City to join the firm of Van Brunt & Howe, who had just established a branch office there. A few years later he studied under former Van Brunt associate William Robert Ware at Columbia University in New York City. He also worked at the firm of A. Page Brown.

Career

In 1896, Polk moved to San Francisco and opened an office, in 1899 launching the influential Architectural News, which lasted three years.[2] Polk was a controversial figure in San Francisco; outspoken, he was described as "obnoxious."[3] He struggled to earn commissions, and in 1897 he declared bankruptcy. However, an opportunity presented itself in 1899. Francis Hamilton, of the local firm Percy & Hamilton, died, and George Washington Percy asked Polk to be his new partner. Polk was primarily in charge of design and employee management, while Percy focused on the business end. The partnership gave Polk a relief to his debt and the opportunity to work on large-scale commercial structures. The partnership designed five buildings, including One Lombard Street. Addison Mizner was one of his apprentices and later a partner.[4]

Willis Polk's early career included work with McKim, Mead & White, as well as Bernard Maybeck.[5] Polk also worked with Daniel Burnham in Chicago, and then moved to San Francisco to establish and direct Burnham's San Francisco office. Before long, Polk started his own firm and spent many years designing highly regarded California commercial and residential architecture.

In 1901, Polk went on a tour of Europe and Chicago. In Chicago, he met prominent architect Daniel Burnham. From 1903 to 1913, Polk was the West Coast representative of D.H. Burnham & Company. Polk designed several of his most notable structures while associated with the firm, including the Merchants Exchange Building, the tallest building in San Francisco upon its completion in 1903. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake opened up numerous opportunities for Polk to design Burnham structures. He was a member of Mayor Eugene Schmitz's Committee of Fifty leaders who undertook ambitious plans to rebuild a world-class city. Polk was tasked with convincing city officials to adopt Burnham's 1905 Plan of San Francisco.

By 1910, Willis Polk was recognized as one of the most influential architects and urban planners in the city. Polk was again credited for designing the tallest building in San Francisco when his Hobart Building was completed in 1914. In 1915, Polk was appointed the chair of the architectural planning committee for the Panama–Pacific International Exposition. When the exposition concluded, Polk led the effort to preserve Bernard Maybeck's Palace of Fine Arts. One of Polk's most influential commissions came in 1916, when he was tasked to design the Hallidie Building. Its glass curtain facade was a precursor to modern skyscraper development. It has been argued to be the most important building in San Francisco. Polk was a versatile architect, with particular skill in combining classical styles with environmental harmony. He was regarded for his elegant residential work, mainly in mansions and estates, in the Georgian Revival style for wealthy and prominent San Francisco residents.

After World War I, Polk's productivity declined. He oversaw the design of the War Memorial Opera House and Veterans Building, part of the planned Civic Center. In 1917, Polk designed but was not involved in the construction of the single family homes at 831, 837, 843 and 849 Mason Street in the exclusive area of Nob Hill in San Francisco at the intersection with California Street opposite the Mark Hopkins Hotel building. 849 Mason Street was redeveloped into four luxury apartments called Four at the Top in 1983 by the restaurateur and wine maker Pat Kuleto.

Legacy and death

Polk died at home in San Mateo, California on September 10, 1924 at the age of 56.[6] He is buried in Santa Clara Mission Cemetery in Santa Clara, California.[6] After his death, his stepson Austin P. Moore ran his business Willis Polk & Co. into the 1930s.[7]

His papers are held at University of California, Berkeley,[8] and scrapbooks are held at the Archives of American Art.[9]

Notable Polk buildings

Public or community buildings

- Carolands Chateau, (1914–1916) estate located in Hillsborough, California. Built by Willis, following the plans of French architect Ernest Sanson. It's both American Renaissance and Beaux-Arts architecture design.

- Filoli Estate (1915–1917) the 16 acre estate is located in Woodside, California.[10] A free Georgian-style architecture that incorporated the tiled roofs commonly found in California.

- First Church of Christ Scientist (1904) at 43 E. Saint James St., San Jose, California. A Neoclassical-style church with the floor in the shape of a Greek cross.[11]

- Hallidie Building, (1917–1918) historic office building located in San Francisco, California.

- Hobart Building, 582–592 Market Street, San Francisco, California

- Le Petit Trianon (1892) located on the grounds of De Anza College in Cupertino, California.

- Merchants Exchange Building (San Francisco)

- Mission Dolores (1917) the reconstruction of the building, which was damaged in the 1906 earthquake.

- Palace of Fine Arts, Polk was the Supervising Architect of the 1915 Exposition[5]

- Pacific Gas & Electric Company, River Station B (1912) at 400 Jibboom Street, Sacramento, California

- Pacific Union Club (1889) brownstone social club located in Nob Hill neighborhood of San Francisco, California.

- Sunol Water Temple (1910) located in Sunol, California. The design of this structure was influenced by the Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, Italy.[12] The temple stands 60 feet tall, with 12 Corinthian columns and a red tile roof, the inner ceiling has a painted wood ceiling which was created by painter Yun Gee.[12]

- Wyntoon (1899) private estate in rural Siskiyou County, California, for attorney Charles Stetson Wheeler, featured in 1899 in The American Architect and Building News

Private residences

- NE corner of 9th & Dolores, Carmel-by-the-Sea, California (for Polk's parents, Willis & Euda Polk)

- 86 Sea View, Piedmont, California (for James K. Moffitt)

- 22 Roble Road, Berkeley, California (for Duncan McDuffie)

- 2550 Webster Street, San Francisco, California (for William Bowers Bourn II, which made clinker brick famous)

- Townhouses at 831-849 Mason Street, San Francisco, California[13]

- Valentine Rey house (1893) 428 Golden Gate Avenue, Belvedere, California. Listed in the National Historic Register.

Further reading

- Dwyer, Michael Middleton. Carolands. Redwood City, CA: San Mateo County Historical Association, 2006. ISBN 0-9785259-0-6

References

- "Willis Jefferson Polk (Architect)". Pacific Coast Architecture Database (PCAD). washington.edu. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- Seebohm, Caroline (2001). Boca Rococo. How Addison Mizner Invented Florida's Gold Coast. Clarkson Potter. p. 55. ISBN 0609605151.

- Seebohm, p. 58.

- Mizner, Addison. The Many Mizners. Chicago: Sears, 1932. p. 75

- McCoy, Esther (1960). Five California Architects. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation. pp. 37–38. ASIN B000I3Z52W.

- "Willis Polk Funeral". Oakland Tribune. 1924-09-12. Retrieved 2019-01-26 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Willis Polk". FoundSF. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- "Willis Polk Collection, 1890-1937 - Collection Number: 1934-1" (PDF). Environmental Design Archives. University of California, Berkeley.

- "Willis Polk scrapbooks, 1908-1924". www.aaa.si.edu. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- Papoulias, Alexander. "'Country Elegance' comes to Woodside in May". PaloAltoOnline.com. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-12-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Sunol Water Temple". San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-05-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)