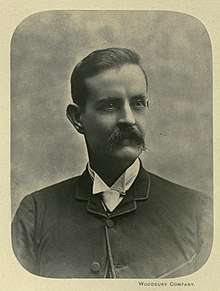

William Ruxton Davison

William Ruxton Davison (died 25 January 1893) was a British ornithologist and collector. Davison was born in Burma but grew up mainly in Ootacamund in southern India. He worked as a private collector and museum curator for Allan Octavian Hume before taking up a position in 1887 as the first director of Raffles Museum in Singapore. He is thought to have committed suicide by opium overdose.

Life and career

Davison came from a family originating in northern England. His father married into a family of modest means and was forced to enlist for service in India. His father worked in the Public Works Department in Burma and became an executive engineer. William and his sister were born in Burma. After the death of his father, his mother moved to settle in Ootacamund in southern India. Here William went to the grammar school run by Rev. G. U. Pope.[1] At the age of sixteen he apprenticed as a chemist at the Cinchona plantation. He them went to Calcutta to work under George King. King noticed his skills for animal observation and recommended him to A. O. Hume. Hume trained Davison for a year and then sent him to various parts of India for periods of six to seven months to collect specimens mostly of birds but also plants.[2] He and Hume were in contact with Nicholas Belfield Dennys at the Raffles Museum.[3] He travelled on behalf of Hume to Tenasserim in the 1870s and collected 8,600 specimens. The results of this were published in a joint article by Davison and Hume, A Revised List of the Birds of Tenasserim (1878). He was considered as one of the best field naturalists of his time.[4] In 1883 Davison made his only trip to England and returned to Ootacamund and got married in 1886. He continued to occasionally work for Hume. Hume who was a corresponding member of the Provincial museum at Lucknow around 1884-85 helped Davison with contracts to collect bird specimens for the museum from around southern India for Rs. 500.[5] Davison had a command of Tamil, Burmese, Malay, and Hindi. Davison was unsuccessful in obtaining a post at the Madras Museum as a replacement for George Bidie[6] and took up position of curator of the Raffles Museum in Singapore from 1887 and where he worked until his death in 1893.[7]

Singapore

Davison's work at the Raffles Museum involved extending the collections, improving access and storage techniques. One of the problems he faced was the humidity and fungal decay of specimens. Davison established a collection strategy based on Wallace's idea on continental boundaries that consisted of marking the boundaries where the sea floor was under 50 fathoms. He personally went on a collection trip along with Henry Nicholas Ridley to Pahang in 1891. The expedition was cut short by news of the death of Davison's wife on 27 March 1891 from bronchitis. It is thought that he was affected by the death of his wife[8] and he became an alcoholic around 1892 and complained of hallucinations, suicidal thoughts and other signs of mental illness. On 14 January 1893 he submitted the annual report for the Raffles Museum for 1892 and on 25 January 1893 he was found dead in his room at Victoria Hotel with symptoms of opium overdose.[3]

Eponyms

Davison is commemorated in the specific name of a number of organisms including the white-shouldered ibis (Pseudibis davisoni ), in a subspecies of the Javanese flying squirrel (Iomys horsfieldii davisoni ), Parymenopus davisoni (a mantid),[9] and in the specific name of an Asian snake (Lycodon davisonii ).[10]

References

- Price, Frederick (1908). Ootacamund. A history. Madras: Government Press. p. 20.

- Hope, C.W. (1899). The ferns of north western India.

- Tan, Kevin Y.L. (2015). Of Whales and Dinosaurs: The Story of Singapore's Natural History Museum. Singapore: NUS Press. pp. 31, 40–48.

- Duff, Sir Mountstuart Elphinstone Grant (1899). Notes from a Diary: Kept Chiefly in Southern India, 1881-1886, Volume 1. John Murray, London. p. 330.

- Minutes of the managing committee from August 1883 to 31st March 1888. Allahabad: Museum Committee. 1899. pp. 22, 33.

- Davison's letter to Albert Günther in NHM Archives. 23 August 1884.

- "Obituary: William Ruxton Davison". Ibis. 35 (3): 478–480. 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1893.tb01235.x.

- Sharpe, Richard Bowdler (1906). "3. Birds". pp. 79-515. In: [Lankester, E.R., ed.] (1906). The history of the collections contained in the natural history departments of the British Museum. 2. Separate historical accounts of the several collections included in the Department of Zoology. [i-iii], [1]-782. London.

- Wood-Mason, J. (1890). "LIII.—Description of a new genus and species(Parymenopus Davisoni)of Mantodea from the Oriental Region". Journal of Natural History. Series 6. 5 (30): 437. doi:10.1080/00222939009460857.

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Davison", p. 66).

Other sources

- Mearns, Barbara and Richard (1998). The Bird Collectors. London: Academic Press. xvii + 472 pp.