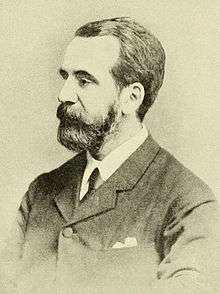

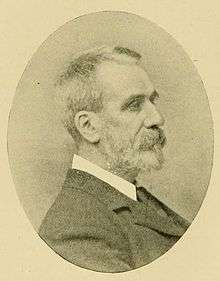

George King (botanist)

Sir George King KCIE FRS FLS VMH (12 April 1840 – 12 February 1909) was a British botanist who was appointed superintendent of the Royal Botanic Garden, Calcutta in 1871, and became the first Director of the Botanical Survey of India from 1890. He was recognised for his work in the cultivation of cinchona and for setting up a system for the inexpensive distribution of quinine throughout India through the postal system.

Early life

George was born in Peterhead, Aberdeenshire, to Robert King and Cecilia Anderson. Robert King was a bookseller who moved to Aberdeen to partner with his brothers who were also in the book business. One brother Arthur was the founder of the Aberdeen University Press. Another brother George was an antiquarian, founder of a local liberal newspaper and a prominent writer on economic and social matters. King's parents both died from phthisis (tuberculosis), the father in November 1845 aged thirty six and the mother in 1850 at the age of forty. Orphaned at the age of ten, George was taken care of by his namesake uncle. After studying at the Aberdeen Grammar School where he was nicknamed "Tertius" to distinguish him from other "King" namesakes, a name that stuck. One of his teachers was Patrick Geddes. Although a good student, his health was poor and he was forced to leave in 1854. The family was associated with the Free church but King later favoured the Anglican church. For a while he worked in his uncle's press business but he continued to take a greater interest in natural history, an interest that had developed in his youth. He started putting together a collection in his work place, something the printer uncle despised. At the age of eighteen King decided to pursue a medical education and entered the University of Aberdeen in 1861, where he was influenced by his teachers George Dickie, Alexander Harvey and John Struthers.

In 1862 King became an assistant to Alexander Dickson. This led to an interest in cryptogamic botany and he was advised by Sir W.J. Hooker to follow the path of Hooker's son (J.D. Hooker) and join the Naval Medical Service. King however was interested in India upon reading Royle and Hooker's works. The Indian Medical Service had suspended recruitment from 1860 but recruitment restarted in April 1865. King obtained an M.B. in 1865 and joined the Indian Medical Service on 2 October, carrying with him an Ipecacuanha plant from Hooker. He left for India in March and reached Calcutta on 11 April 1866.[1]

India

King was initially appointed to the General Hospital before transferring to the Medical College Hospital where he was made house surgeon. He fell ill with pneumonia and it was suggested that he transfer to a drier climate. He was posted to Agra on 4 September and was attached to the 41st Bengal Infantry. He moved to Mathura in January 1867. Bouts of illness continued and it was suggested that he should move to central India. He was posted to Guna in February 1867, taking charge of the Central India Horse. The next year he moved to Rajputana with stints at Deoli, Mount Abu and Jodhpur before moving to the Botanic Garden at Saharanpur. At the end of 1869, as his term was ending at Saharanpur, he was invited to join the Forest Department as an Assistant Conservator.[1]

In his postings in India, he worked during his leisure time on its plants, making a study of the famine plants. He also made an ornithological survey of Guna. The posting in Dehra Dun gave him more time for study. King found that the forests of the Doon were being destroyed with a system of bribery and corruption within the Forest Department. King worked to eliminate the corrupt officials. In January 1871 King moved to the Kumaon Forest Division and prepared a report on the forests of Ranikhet. He also contributed to the botanical sections of the Gazetteers. It was recommend that he be made a permanent Deputy Conservator.

In 1869, the Superintendent of the Royal Botanic Garden, Calcutta, Thomas Anderson, fell ill (left for Europe and died in 1870) and in 1871, the Secretary of State for India selected King as a successor. King took up the position and was also a Professor of Botany in the Medical College of Bengal. King was faced by the destruction wrought by two cyclones in 1864 and 1867. King was also involved in matters associated with tea and cinchona cultivation. While on an official visit to the Nilgiris in July 1872, he developed symptoms of pulmonary phthisis(tuberculosis). He was treated in Coonoor before moving to Europe. He spent a year in the Riviera and returned to Calcutta to resume duties in November 1873. King restructured the Calcutta Botanical Gardens, raising the level of the ground, creating ponds and laying out footpaths and conservatories. A fireproof herbarium was also constructed based on plans from Kew. King also altered the garden design from one segregated linearly on the basis of taxonomy to one based on regions with combinations of species showing the natural plant associations.[1] He began the journal, the Annals of the Royal Botanic Garden, Calcutta

In 1873 King was also associated with the creation of the Calcutta Zoological Garden. He was also associated with setting up a botanical garden at Darjeeling. King had earlier suggested that a post for a quinologist be created and the appointee C.H. Wood found a way to extract alkaloids and this helped produce a popular Cinchona Febrifuge. Wood returned in 1879 but his setup was worked by J.A. Gammie. King replaced the quinologist, studying the methods of the Dutch and went on furlough to England in 1885 to study Wood's continued work back there. Returning to India, King worked on a system for the distribution of quinine through the postal department. The system was fully operational in 1893.[1] Village post offices in Bengal were able to sell small packets for a pice, the smallest coinage.[3]

He also supervised the work of botanical artists and worked with Sir Joseph Hooker to help him prepare the Flora of British India. A major work was on the Annonaceae of British India.[4] In 1891, he was appointed the first director of the Botanical Survey of India, an institution that linked the botanical officers in the different Presidencies.[1] King also produced a work on the orchids of the eastern Himalayas, The Orchids of the Sikkim-Himalayas (1898) in the Annals along with Robert Pantling (1857–1910) who was an assistant in the Mungpoo cinchona plantations working with James Alexander Gammie.[5] King also wrote a series of articles Materials for a Flora of the Malayan Peninsula in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.[6]

In 1898 King was succeeded at the Calcutta Botanical Gardens by Sir David Prain (1857–1944).

Personal life and last years

King married Jane Anne Nicol (1845-1898) in 1868. Jane fell ill and died on the way back to England in 1898. The loss was a blow and in the following years King lost an eye due to a ruptured vessel and he increasing fell ill. He reflected on the history of botany in India at the 69th meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1899.[7] He died of a seizure at San Remo on 12 February 1909.[1]

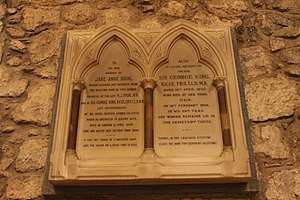

He is buried in the cemetery in San Remo but is memorialised on the grave of his wife in St Machar's Cathedral in Old Aberdeen.

Botanical reference

Species described by him include the climbing fig Ficus pantoniana from New Guinea and northern Australia.[8]

Honours and memorials

King took an interest in the Asiatic Society of Bengal, was sometime president of the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India. He also encouraged research among his friends. David Douglas Cunningham and Arthur Barclay helped him on matters of plant pathology. He received a degree of LL.D. in 1884 and was elected to the Royal Society in 1887.[9] As a landscape gardener, he was recognised by the Royal Horticultural Society and awarded the Victoria Medal of Honour in 1901. He was awarded the Linnean Medal in 1901.

For his work on making quinine and distributing it inexpensively he was made an honorary member of the Pharmaceutical Society and given a ring of honour by Czar Alexander III. On 1 January 1890 he was invested as a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire.[10] In 1898 he was created K.C.I.E. A memorial was built at San Remo, where he visited every winter from 1898 until his death.[1] There is a memorial plaque to him and his wife in St Machar's Cathedral, Old Aberdeen.

References

- Prain, David (1909). "Obituary notices of fellows deceased: Sir George King". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 81 (551): xi–xxviii. doi:10.1098/rspb.1909.0046.

- Anonymous (27 February 1909). "The late Sir George King". The Gardeners' Chronicle: 138.

- "New Year Honours". British Medical Journal. 1 (1932): 106. 1898. PMC 2410470. PMID 20757531.

- King, G (1893). "Annonaceae of British India". Annals of the Royal Botanic Garden, Calcutta. 4.

- Stafleu, Frans A. (1968). "Review: A Century of Indian Orchids Selected from Drawings in the Herbarium of the Botanic Garden, Calcutta by J. D. Hooker; The Orchids of the Sikkim-Himalaya by George King, Robert Pantling; The Orchids of the North-Western Himalaya by J. F. Duthie". Taxon. 17 (3): 293–295. doi:10.2307/1217713.

- Anonymous (27 February 1909). "The late Sir George King". The Gardeners' Chronicle: 138.

- King, Sir George. 1899. The Early History of Indian botany. Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. pp. 904-919.

- King, G. (1887). "Part 2. Natural history". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 55 (2): 407.

- "Fellow details". Royal Society. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "Brigade Surgeon King, Superintendent of Royal Botanic Gardens, Calcutta". Aberdeen Journal. 14 May 1890. p. 6.

- IPNI. King.