William Olander

William "Bill" R. Olander (July 14, 1950 – March 18, 1989) was an American senior curator at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York City. He previously worked as curator and director of the Allen Memorial Art Museum. He was a co-founder of the Visual AIDS art project.

William Olander | |

|---|---|

| Born | July 14, 1950 Minneapolis, Minnesota, US |

| Died | March 18, 1989 (aged 38) Minneapolis |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Bill Olander |

| Education | PhD, art history, New York University Institute of Fine Arts, 1983 |

| Occupation | Museum curator |

| Years active | 1985–1989 |

| Employer | New Museum of Contemporary Art |

| Partner(s) | Christopher Cox |

Early life

William R. Olander was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on July 14, 1950, the son of Clarence Emil Olander (1928-1988) and Isabelle Olander née Marcucci (1928-2015).[1] He moved to New York City in the 1980s.[2]

Olander attended the New York University Institute of Fine Arts where in 1983 he obtained an Art History Ph.D. with the thesis "Pour transmettre a la posterite: French Painting and Revolution 1774–1795".[2][3] The unpublished thesis was considered a reference work:[4] Olander was one of the first to highlight the importance of the 1792 proclamation of La patrie en danger.[5]

Career

In 1979 Olander became modern art curator at the Allen Memorial Art Museum run by Oberlin College;[6] from 1983 to 1984 he was acting director.[2] In 1980 Olander contributed text to the museum exhibition "From Reinhardt to Christo". In 1981 Olander curated the exhibition "Young Americans" and in 1984 the exhibition "New Voices 4: Women & The Media, New Video".[7]

In 1982 Olander contributed an essay to Face It: 10 Contemporary Artists, a catalogue for the exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, and in 1984 he curated the exhibition Drawings: After Photography and contributed texts to its catalogue.[8]

From 1985 he was a curator at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York City, and specialized in performance art and video, especially post-modernist language and theory.[2]

In 1985 Olander curated the exhibition "The Art of Memory/The Loss of History".[9][2] Olander's most famous exhibition is the 1986 "Homo Video: Where are We Now, a program of Video Tapes by Gay Men and Lesbians", including video which responded to the spreading of the AIDS virus. However both Lesbian and Gay artists and photographers were disappointed by the exhibition and Olander referred to it "as a stunning failure with regard to homosexuality".[10][11]

In 1987 he curated the exhibition On View at the New Museum. "The Window on Broadway by Act Up.", which included the ACT UP installation "Let the Record Show...", a workspace "Social Studies: Recent Work on Video and Film" and paintings by Charles Clough and Mimi Thompson.[12] Another 1987 exhibition was "FAKE", which focused on the relationship between authenticity and the postmodern notions of "the fake" or "the counterfeit".[13]

In 1988 Olander contributed the essay An Artistic Agenda to LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions), 10 yrs. documented, [14] and to One Plus or Minus One, with Lucy Lippard.

Both Discourses: Conversations in Post Modern Art and Culture, of which Olander was coeditor with Russell Ferguson, Marcia Tucker and Karen Fiss, and Discussions in contemporary culture, to which Olander contributed two essays, were published posthumously in 1990.[15][16]

Let the Record Show

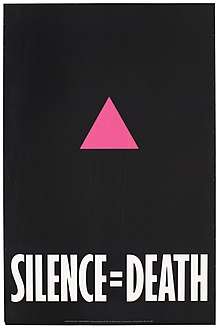

In 1987 he invited the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) group to present an installation for the museum's window facing Broadway. The installation, created by the art collective Gran Fury, was a collage of information on AIDS, and was presented in a way that expressed the general public indifference to AIDS victims.[2] Olander explained, "The majority of the sitters are shown alone [...] they have no identities other than as victims of AIDS".[17] Olander invited ACT UP to mount the installation after an anonymous poster bearing the phrase Silence=Death began appearing throughout Manhattan.[18] "Let the Record Show" (1987) is now an iconic installation at the New Museum.[10] Olander compared the installation "Let the Record Show" to Jacques-Louis David's The Death of Marat.[18]

Olander's name on the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt reads: "Let the record show that there are many in the community of art and artists who choose not to be silent in the 1980s".[10]

Visual AIDS

In 1988 Olander, together with Robert Atkins (writer/curator), Thomas Sokolowski (then Director of The Grey Art Gallery), and Gary Garrels (then Director of Programs at Dia Art Foundation), created Visual AIDS, a loosely-organized coalition of arts professionals working to encourage discussion of the pressing social issues of the AIDS epidemic.[19] Every year Visual AIDS presents the "Bill Olander Award" to art workers or artists living with HIV.[10]

Personal life and death

Olander's longtime companion was Christopher Cox.[2] Olander died on March 18, 1989, from causes related to HIV/AIDS. He is buried at Lakewood Cemetery, Minneapolis. When Olander's obituary ran in The New York Times, Cox's name was initially omitted, only to be corrected later. Cox died 18 months later, on September 7, 1990.[2][10]

References

- "Burial Search Search Lakewood's burial/memorial database online". Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "William Olander, 38, Art Curator, Is Dead". The New York Times. 21 March 1989. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Bryson, Norman; Holly, Michael Ann; Moxey, Keith (1994). Visual Culture: Images and Interpretations. Wesleyan University Press. p. 165. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Wintermute, Alan; Bailey, Colin B.; Olander, William; Eliel, Carol S. (1989). 1789: French art during the revolution. Colnaghi. p. 27.

- Mainz, Valerie (2016). Days of Glory?: Imaging Military Recruitment and the French Revolution. Springer. p. 177. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Allen Memorial Art Museum Bulletin. Department of Fine Arts of Oberlin College. 1979. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Bulletin, Volumi 44-46. Allen Memorial Art Museum. 1990. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Grundberg, Andy (1990). Crisis of the Real: Writings on Photography, 1974-1989. Aperture. p. 106. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- McCarthy, David (2015). American Artists Against War, 1935 2010. Univ of California Press. p. 215. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Kerr, Ted. "Remembering William Olander". THE VISUAL AIDS BLOG. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Boffin, Tessa; Fraser, Jean (1991). Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs. Pandora. p. 10. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Brochure for On View at the New Museum. "The Window on Broadway by Act Up."". New Museum. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Chen, L. (2006). Writing Chinese: Reshaping Chinese Cultural Identity. Springer. p. 17. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Moss, Karen; Pritikin, Renny; Olander, William (1988). LACE, 10 yrs. documented. LACE. p. 16. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Jung, Hwa Yol (2011). Transversal Rationality and Intercultural Texts: Essays in Phenomenology and Comparative Philosophy. Ohio University Press. p. 340. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Dia Art Foundation (1990). Discussions in contemporary culture, Edizione 5. Bay Press. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Stanton, Domna C. (1992). Discourses of Sexuality: From Aristotle to AIDS. University of Michigan Press. p. 373. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Ault, Julie (1999). Art Matters: How the Culture Wars Changed America. NYU Press. p. 102. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Junge, Sophie (2016). Art about AIDS: Nan Goldin's Exhibition Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 116. Retrieved 1 August 2017.