William Johnson (artist)

William Henry Johnson (March 18, 1901 – April 13, 1970) was an American painter. Born in Florence, South Carolina, he became a student at the National Academy of Design in New York City, working with Charles Webster Hawthorne. He later lived and worked in France, where he was exposed to modernism. After Johnson married Danish textile artist Holcha Krake, the couple lived for some time in Scandinavia. There he was influenced by the strong folk art tradition. The couple moved to the United States in 1938. Johnson eventually found work as a teacher at the Harlem Community Art Center, through the Federal Art Project.

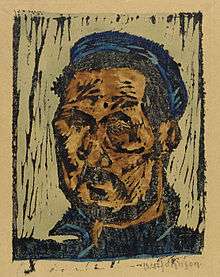

William H. Johnson | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, c. 1930–1945 | |

| Born | William Henry Johnson March 18, 1901 |

| Died | April 13, 1970 (aged 69) |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse(s) | Holcha Krake |

| Awards | Harmon Foundation Gold Medal for Excellence in Fine Arts[1][2] |

| Patron(s) | Charles Hawthorne |

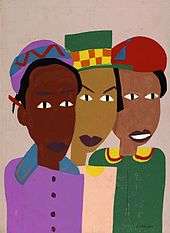

Johnson's style evolved from realism to expressionism to a powerful folk style, for which he is best known. A substantial collection of his paintings, watercolors, and prints is held by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which has organized and circulated major exhibitions of his works.

Education

William Henry Johnson was born March 18, 1901, in Florence, South Carolina, to Henry Johnson and Alice Smoot.[3] He attended the first public school in Florence, the all-black Wilson School on Athens Street. It is likely that Johnson was introduced to sketching by one of his teachers, Louise Fordham Holmes, who sometimes included art in her curriculum.[4]:6 Johnson practiced drawing by copying the comic strips in the newspapers, and considered a career as a newspaper cartoonist.[4]:9[5]

He moved from Florence, South Carolina, to New York City at the age of 17. Working a variety of jobs, he saved enough money to pay for classes at the prestigious National Academy of Design.[4][6] He took a preparatory class with Charles Louis Hinton, then studied with Charles Courtney Curran and George Willoughby Maynard, all of whom emphasized classical portraiture and figure drawing. Beginning in 1923, Johnson worked with the painter Charles Webster Hawthorne, who emphasized the importance of color in painting. John studied with Hawthorne at the Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown, Massachusetts during the summers, paying for his tuition, food and lodging by working as a general handyman at the school.[4]:10–17 Johnson received a number of awards at the National Academy of Design, and applied for a coveted Pulitzer Travel Scholarship in his final year. When another student was given the award, Hawthorne raised nearly $1000 to enable Johnson to go abroad to study.[3][4]:21

Career

Johnson arrived in Paris, France in the fall of 1927. He spent a year in Paris, and had his first solo exhibition at the Students and Artists Club in November 1927.[7] Next he moved to Cagnes-sur-Mer in the south of France, influenced by the work of expressionist painter Chaim Soutine.[4]:27–31 In France, Johnson learned about modernism.[8]

During this time, Johnson met the Danish textile artist Holcha Krake (April 6, 1885 – January 13, 1944).[9] Holcha was traveling with her sister Erna, who was also a painter, and Erna's husband, the expressionist sculptor Christoph Voll. Johnson was invited to join them on a tour of Corsica. Johnson and Holcha were deeply attracted in spite of differences in race, culture, and age.[4]:35–36

Johnson returned to the United States in 1929. Fellow artist George Luks encouraged Johnson to enter his work at the Harmon Foundation to be considered for the William E. Harmon Foundation Award for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes in the Fine Arts Field. As a result, Johnson received the Harmon gold medal in the fine arts.[1][2] He was applauded as a "real modernist", "spontaneous, vigorous, firm, direct".[4]:41 Other winners of the fine art award include Palmer Hayden, May Howard Jackson and Laura Wheeler Waring.[4]:41

While in the United States, Johnson also visited his family in Florence, where he painted a considerable number of new works. He was apparently almost arrested while painting the Jacobia Hotel, a once-fashionable town landmark which had become a dilapidated house of ill-repute. Whether Johnson's actions or his choice of subject were at issue is unknown.[2][4]:51 During this visit, Johnson was able to publicly exhibit his paintings twice. The first occasion was at a meeting of the Florence County Teachers Institute on February 22, 1930. The second was at a local YMCA where Johnson's mother worked. Her boss, Bill Covington, arranged for Johnson to exhibit 135 of his paintings for a single afternoon, on April 15, 1930.[2] Although the Florence Morning News described Johnson condescendingly as a "humble ... Negro youth", it also stated that he had "real genius".[4]:51

Johnson returned to Europe in 1930 by working his way to France on a freighter. He went to Funen, a Danish island, to rejoin Holcha Krake. The couple signed a prenuptial agreement on May 28, 1930, and were married a few days later in the town of Kerteminde.[4]:55 Johnson and his wife spent most of the 1930s in Scandinavia, where his interest in folk art influenced his painting. However, as Nazi sentiments increased in Germany and Europe in the late 1930s, many artists were affected. Johnson's brother-in-law Christoph Voll was fired from his teaching position, and his art was labelled "degenerate". Johnson and Krake chose to move to the United States in 1938.[4]:117[8]

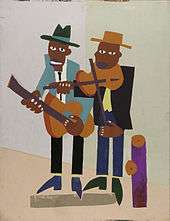

With the help of Mary Beattie Brady, Johnson eventually found work as a teacher at the Harlem Community Art Center. There he and other teachers instructed about 600 students per week, as part of a local Federal Art Project supported by the Works Progress Administration. Through the center Johnson met important Harlem inhabitants such as Henry Bannarn and Gwendolyn Knight.[4]:124 He immersed himself in African-American culture and traditions, producing paintings that were characterized by their folk art simplicity.[10] Johnson was determined to "paint his own people".[4]:123 He celebrated African American culture and imagery in the urban settings of pieces such as Street life - Harlem, Cafe, and Street Musicians, and in the rural settings of Farm Couple at Work, Sowing, and Going to Market. Harsher realities of Negro life were depicted in Chain Gang and Moon over Harlem, which was a response to the 1943 racial riots in New York. Another series of works showed war-time soldiers and nurses.[4]:123–180 Johnson held a solo exhibition at Alma Reed Galleries in 1941.[3] However, although he enjoyed a degree of success as an artist during the 1940s and 1950s, he was never able to achieve financial stability.[3]

On a personal level, the 1940s were difficult. Bad news came from Europe. Christoph Voll died in Karlsruhe, Germany, on June 16, 1939, after interrogation by Nazi officials. Holcha's family endured the German occupation of Denmark at their home in Odense.[4]:155 In December 1942, Johnson and Krake moved to a larger studio apartment in Greenwich Village. A week later, Johnson's artwork, supplies, and personal possessions were destroyed when the building caught fire.[3][4]:170 On January 13, 1944, John suffered further loss when his wife Holcha died from breast cancer.[4]:181–182[9] To deal with his grief, he revisited his family in Florence, and painted works with religious themes, such as Mount Calvary.[4]:190–191 Mount Calvary and Booker T. Washington Legend (from Johnson's Fighters for Freedom series of 1945) were included in the show The Negro Artist Comes of Age: A National Survey of Contemporary American Artists at the Albany Institute of History and Art in 1945.[4]:200, 203

In 1946 Johnson left for Denmark to be with his wife's family. However, his behavior became increasingly erratic. At Ullevål Hospital in Oslo in spring 1947, he was diagnosed as suffering from syphilis which had impaired both mental and motor function. As a U.S. citizen who was no longer considered mentally competent, he was sent back to New York by the U.S. Embassy in Oslo. An attorney was appointed by the court as his legal guardian, and his belongings were put into storage. He entered the Central Islip State Hospital on Long Island on December 1, 1947, where he was treated for syphilis-induced paresis.[4]:219–220[11] He spent the last twenty-three years of his life there. He no longer painted after 1955 and died on April 13, 1970, of hemorrhaging of the pancreas.[4]:223, 227

Recognition

In 1956, Johnson's life's work was almost destroyed when his caretaker declared him unable to pay further storage fees.[10][12] Instead, Helen Harriton, Mary Beattie Brady, and others arranged with the court to have Johnson's belongings delivered to the Harmon Foundation with unconditional rights over all works. The foundation would use the works to advance interracial understanding and support African American achievements in the fine arts. On April 19, 1967, the Harmon Foundation gave more than 1,000 paintings, watercolors, and prints by Johnson to the Smithsonian American Art Museum.[4]:223–225

In 1991, the Smithsonian American Art Museum organized and circulated a major exhibition of his artwork, Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson,[13] and in 2006, they organized and circulated William H. Johnson's World on Paper.[14] An expanded version of this exhibition traveled to the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas,[15] the Philadelphia Museum of Art,[16] and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in Montgomery, Alabama in 2007.[15]

The William H. Johnson Foundation for the Arts was established in 2001 in honor of the 100th birthday of William Johnson.[17] Beginning with Laylah Ali in 2002, the Foundation has awarded the William H. Johnson Prize annual to an early career African American artist.[18][19]

In 2012, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in Johnson's honor, recognizing him as one of the nation's foremost African-American artists and a major figure in 20th-century American art. The stamp, the 11th in the "American Treasures" series, showcases his painting Flowers (1939–40), which depicts brightly colored blooms on a small red table.[20]

References

- Lord, M. G. (January 3, 1999). "A Wrangle Over a Rediscovered Artist". The New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "William H. Johnson Biography: Part III". Florence County Museum. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "William H. Johnson Biography Painter (1901–1970)". The Biography.com website. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- Powell, Richard J.; Puryear, Martin (1991). Homecoming: the art and life of William H. Johnson. Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0-393-31127-3.

- "William H. Johnson Biography: Part II". Florence County Museum. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- Driskell, David; Lewis, David Levering; Ryan, Deborah Willis; Campbell, Mary Schmidt (1987). Harlem Renaissance: art of Black America. New York: The Studio Museum in Harlem. ISBN 0-8109-1099-3.

- Wintz, Cary D.; Finkelman, Paul (2004). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-57958-389-7. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- Gopnik, Blake (June 25, 2006). "William H. Johnson's Taste of Europe". The Washington Post Company. Retrieved July 6, 2006.

- "Artist: Holcha Krake". Kunstindeks Danmark. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "William H. Johnson". Smithsonian American Art Museum. United States of America. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- "The Art and Life of William H. Johnson". Black Art Depot. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Greenwald, Xico (March 18, 2014). "Unpolished Expression". The New York Sun. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- Poesch, Jessie (1995). "Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson (review)" (PDF). Southern Cultures. 1 (3): 367–369. doi:10.1353/scu.1995.0100.

- "William H. Johnson's World on Paper". Smithsonian American Art Museum.

- Kantrowitz, Jonathan (June 25, 2013). "William H. Johnson's World on Paper". Art History News. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- "William H. Johnson's World on Paper". Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- "Foundation History". The William H. Johnson Foundation for the Arts. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "William H. Johnson Prize Winners". The William H. Johnson Foundation for the Arts. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "2013 William H. Johnson Prize". Art Agenda. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "William H. Johnson Forever Stamp Available Today". United States Postal Service. April 11, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

External links

- The William H. Johnson Foundation For The Arts

- Works by William H. Johnson in the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

- William H. Johnson gallery at Smithsonian American Art Museum on Flickr

- William H. Johnson Biography: New Beginnings, Part I, Part II, Part III, Florence County Museum