White Shoulders

White Shoulders is a lost[4] 1931 American pre-Code comedy-drama film directed by Melville W. Brown and starring Mary Astor and Jack Holt, with major supporting roles by Ricardo Cortez and Sidney Toler.[5] The film was produced and distributed by RKO Pictures. The screenplay by Jane Murfin and J. Walter Ruben was adapted from Rex Beach's short story, The Recoil.

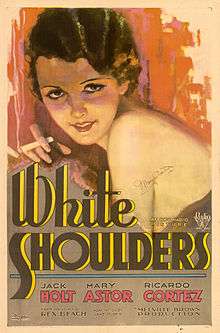

| White Shoulders | |

|---|---|

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Melville W. Brown |

| Produced by | William LeBaron Henry Hobart (associate) |

| Screenplay by | Jane Murfin[1] J. Walter Ruben[1] |

| Based on | the short story, Recoil by Rex Beach[2] |

| Starring | Mary Astor Jack Holt |

| Cinematography | Jack MacKenzie[2] |

| Distributed by | Radio Pictures (aka RKO Pictures) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 80 minutes[3] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The film touched on the topics of gold-digging, adultery, bigamy, gigolos, and theft. The rights to the story were optioned in late 1930, and the film went into production in March 1931. After approximately four weeks of filming, the film was screened in May.

A remake of the 1924 silent film entitled The Recoil, RKO released the film on June 6, 1931, and it did not perform well at the box office, making it yet another film by RKO to suffer a similar fate. Critically, it was a mixed batch of opinions, ranging from poor to very good. Most reviewers enjoyed at least some of the acting, but virtually all thought the plot was either too convoluted or simply implausible, although some at least gave it credit for its originality.

Plot

Norma Selbee is a chorus girl trying to make it in New York City. Her fortunes are not going well, and she is flat broke and on the verge of starvation when she meets Gordon Kent. Kent has spent the last several years in the back woods, utilizing his mining engineering acumen to accumulate a large fortune of approximately $20 million. He has come to the big city looking for a good time, hopefully among the "white shoulders" of the fair damsels of the Big Apple. Upon meeting Norma, he falls head over heels for her and proposes on their first evening together. Norma is reluctant to agree, for she is not a gold-digger, and she is not in love with Kent. But she has no prospects, and she feels that she may come to love him in time, so she agrees, and the two are immediately married.

In a whirlwind of activity, Kent books them on a ship to Europe for their honeymoon which is leaving shortly. On the trans-Atlantic crossing, and upon their arrival on the continent, Kent showers Norma with gifts and fine living. Somehow, she still finds a way to feel unwanted by him. While she wishes that he would spend more time with her, rather than money on her, he also has a business he still has to run. When they travel to Paris, they run into an old acquaintance of Norma's, Lawrence Marchmont, who instantly understands a meal ticket when he sees one. As Kent is distracted by his business dealings, he begins to woo the lonely Norma. She at first resists his advances, but eventually succumbs to Marchmont's attentions, and the two run off together.

Devastated, Kent hires investigators to look into the background of the pair. It is discovered that Marchmont's real name is Tommy Pierce, a two-bit con artist who is wanted by the police in several countries. Kent also finds out that Norma's first husband, who Kent knew about, never legally divorced Norma, so technically she is a bigamist. Deciding to teach the pair a lesson, he pairs the private investigators to follow them and ensure that they cannot part from one another. It soon becomes apparent to Norma that the only thing that Marchmont/Pierce was interested in was her jewels, and she has to resume her chorus girl activities in order to support Marchmont/Pierce's drinking habit. However, when either of the two attempts to leave, they are returned to each other, under threat of turning them over to the police for arrest. There are only two problems with this plan: Kent is love Norma; and Norma has fallen in love with Kent.

Marchmont/Pierce thinks he has figured a way out of the unpleasant situation when Norma's first husband, Jim Selbee, turns up. The two plan a blackmail scheme to be hatched on Kent, only to have it foiled by Norma. With that plan spoiled, the two con-men turn to plan "B", deciding to abscond with Norma's jewels. The night of the robbery, as they are breaking into the safe, the pair argue, resulting in Marchmont/Pierce shooting Selbee, and killing him. Marchmont/Pierce is arrested for the murder, and with Selbee out of the way, Norma is free to return to Kent. She is reticent, due to her guilt over her relationship with Marchmont, but Kent convinces her to return, and the pair is reunited.

Cast

(Cast list as per AFI database, and The RKO Story)[1][2]

- Mary Astor - Norma Selbee

- Jack Holt - Gordon Kent

- Ricardo Cortez - Lawrence Marchmont

- Sidney Toler - William Sothern

- Kitty Kelly - Maria Fontaine

- Robert Keith - Jim Selbee

- Nicholas Soussanin - Head waiter

Notes

This would be the transition role for Mary Astor, who up until this time had only been cast in "featured" roles, which technically her role in this film was as well. Starting with her next picture, Nancy's Private Affair, she would be moved up to starring status.[6] Lita Chevret had a minor role in the film.[7]

Production

Rex Beach wrote a short story, "The Recoil", which appeared in the November 1922 issue of Cosmopolitan. It was optioned by Goldwyn Pictures, which produced a silent film of the same name in 1924.[8] RKO acquired the rights for the story, along with two other Beach stories, The Slander Girl and Young Donovan's Kid,[9] and in October 1930 it was added to their production schedule. At the same time Melville Brown was picked to direct by producer William LeBaron, and Evelyn Brent was announced as the lead.[10] By February 1931, Brent had been replaced by Mary Astor in the cast, and joined by Jack Holt and Ricardo Cortez.[11] In mid-February Kitty Kelly was added to the performers,[12] with Sidney Toler joining the cast less than a week later.[13]

By the beginning of March, Brown had finalized the main members of his cast. He asked fellow director and screenwriter Howard Estabrook to take the script and clean and tighten it, although he was given no screen credit for his efforts.[14] By the middle of the month, Brown had the cast in rehearsals,[15] and began filming by March 22.[16] After filming had commenced, Brown added the final two cast members, Nicholas Soussanin and Robert Keith.[17][18] The new technology of the "Dunning Process" (to adapt the film into foreign languages) was used in filming, but there is no record of the film ever being produced in a foreign language.[19] Principal photography on the film was completed by the middle of April,[20] and the film was being screened by industry professionals by the end of the month.[21] The film began receiving reviews on May 17, 1931,[22] which has led some modern sources to incorrectly date this as the film's release date.[23] The film premiered in New York City at the Mayfair Theater on June 6, 1931.[2][24]

Reception

The film did not perform well at the box office, and was not one of the few films released by RKO that year which posted a profit.[25] Mordaunt Hall, critic for The New York Times was less than impressed by the film, calling it "unbelievable", and stating that both the script and the acting were "crude". He did, however, give credit to the performance of Sidney Toler, as the one bright spot for the film.[26] Modern Screen only rated the film "fair", making the comment that the actors tried their best with the material given them, but they could only do so much with the improbable plot.[27] Motion Picture Daily also referenced the improbable plot, while giving credit to the attempts by the acting crew to overcome the material. They went on to call Brown's direction, "ineffectual".[28] Screenland called it a "weak melodrama", and gave credit to the cast for attempting to overcome the implausible script.[29][30]

The film did receive several positive reviews. The Film Daily called the film a "... good number for sophisticated audiences ...", giving good marks to the direction and photography, but criticizing the script for creating "artificial" situations.[22] Other publications which had some positive comments about the film included: the Boston Globe, which applauded the acting; the Boston Traveler, which said the plot was novel; the Portland Evening News which thought the film was "Interesting and original"; and the Detroit Daily Mirror which said, "Vivid drama ... good audience stuff".[31] The Motion Picture Herald enjoyed the film, calling it "... better than average screen entertainment," and "... adult and thought-provoking drama." They singled out the acting abilities of Astor, Cortez and Kelly, particularly Astor, of whom they said, "It should do much in establishing the talents of the charming Mary Astor as a stellar personality." They were less kind to Holt's performance, and felt that overall the film did not go far enough in exploring the fall from grace of Astor and Cortez characters when they are forced to live together.[32] While not a stellar review, Silver Screen magazine said White Shoulders was a "good" film, complimenting the novel plot twists, and the performances of Astor, Holt and Cortez.[33]

References

- Jewell, Richard B.; Harbin, Vernon (1982). The RKO Story. New York: Arlington House. p. 36. ISBN 0-517-546566.

- "White Shoulders: Detail View". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 2, 2014. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- "White Shoulders: Technical Details". theiapolis.com. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- The Magnificent Heel: The Life and Films of Ricardo Cortez by Dan Van Neste c.2018 ISBN 978-1-62933-128-7

- The American Film Institute Catalog Films: 1931-40 by The American Film Institute, c. 1993

- "Gallery of Honor". The Modern Screen Magazine. June 1931. p. 80.

- "On The Dotted Line..." Motion Picture Herald. April 11, 1931. p. 60.

- "The Recoil: Detail View". American Film Institute. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- "Delores Del Rio Contract For Year, Says LeBaron". Motion Picture Herald. April 25, 1931. p. 66.

- Wilk, Ralph (October 29, 1930). "A Little from "Lots"". The Film Day. p. 8.

- "Hollywood Activities: Mel Brown on New RKO Special". The Film Daily. February 15, 1931. p. 4.

- "Latest Hollywood Happenings: Kitty Kelly in White Shoulders". The Film Daily. February 19, 1931. p. 9.

- Wilk, Ralph (February 25, 1931). "Hollywood Flashes". The Film Daily. p. 7.

- Wilk, Ralph (March 6, 1931). "A Little from "Lots"". The Film Daily. p. 8.

- "16 Feature Productions Being Prepared at RKO". The Film Daily. March 15, 1931. p. 2.

- "Henry Hobart Assigned Four RKO Productions". The Film Daily. March 22, 1931. p. 2.

- "Latest Hollywood Happenings: Soussanin in RKO Pictures". The Film Daily. April 1, 1931. p. 6.

- "Hollywood Happenings: Robert Keith in "White Shoulders"". The Film Daily. April 10, 1931. p. 47.

- "Dunning Process Corporation". International Photographer. April 1931. p. 35.

- "Two Big Productions Completed by Radio". The Film Daily. April 12, 1931. p. 29.

- "New Methods Constantly Being Evolved, RCA Head Declares". The Film Daily. April 29, 1931. p. 7.

- "White Shoulders". The Film Daily. May 17, 1931. p. 10.

- "White Shoulders". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- "The Release Chart". Motion Picture Herald. May 30, 1931. p. 74.

- Jewell 1982, p. 32.

- Hall, Mordaunt (June 5, 1931). "The Impulsive Millionaire. A Blue-Eyed Siren". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- "The Modern Screen Directory: White Shoulders". Modern Screen. September 1931. p. 9.

- "Dead to Rights". Motion Picture Daily. June 12, 1931. p. 2.

- "Revuettes: White Shoulders". Screenland. September 1931. p. 102.

- "Critical Comment on Current Films". Screenland. September 1931. p. 85.

- "Copy ... Boy! ... and Make the First Edition!". Motion Picture Daily. July 8, 1931. p. 2.

- "White Shoulders". Motion Picture Herald. May 30, 1931. p. 54.

- "Talkies in Tabloid". Silver Screen. September 1931. p. 65.