Wheat Fields

The Wheat Fields is a series of dozens of paintings by Vincent van Gogh, borne out of his religious studies and sermons, connection to nature, appreciation of manual laborers and desire to provide a means of offering comfort to others. The wheat field works demonstrate his progression as an artist from the drab Wheat Sheaves made in 1885 in the Netherlands to the colorful, dramatic paintings from Arles, Saint-Rémy and Auvers-sur-Oise of rural France.

| Landscape with Wheat Sheaves and Rising Moon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | early June, 1889 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 72.0 cm × 92.0 cm (28.3 in × 36.2 in) |

| Location | Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands |

Wheat as a subject

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Failing to find a vocation in ministry, Van Gogh turned to art as a means to express and communicate his deepest sense of the meaning of life. Cliff Edwards, author of Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest wrote: "Vincent's life was a quest for unification, a search for how to integrate the ideas of religion, art, literature, and nature that motivated him."[1]

Van Gogh came to view painting as a calling, "I feel a certain indebtedness [to the world] and ... out of gratitude, want to leave some souvenir in the shape of drawings or pictures – not made to please a certain taste in art, but to express a sincere feeling."[2] When Van Gogh left Paris for Arles, he sought an antidote to the ills of city life and work among laborers in the field "giving his art and life the value he recognized in rural toil."[3]

In the series of paintings about wheat fields, Van Gogh expresses through symbolism and use of color his deeply felt spiritual beliefs, appreciation of manual laborers and connection to nature.

Spiritual significance

As a young man Van Gogh pursued what he saw as a religious calling, wanting to minister to working people. In 1876 he was assigned a post in Isleworth, England to teach Bible classes and occasionally preach in the Methodist church.[4][5]

When he returned to the Netherlands he studied for the ministry and also for lay ministry or missionary work without finishing either field of study. With support from his father, Van Gogh went to Borinage in southern Belgium where he nursed and ministered to coal miners. There he obtained a six-month trial position for a small salary where he preached in an old dance hall and established and taught Bible school. His self-imposed zeal and asceticism cost him the position.[5]

After a nine-month period of withdrawal from society and family; he rejected the church establishment, yet found his personal vision of spirituality, "The best way to know God is to love many things. Love a friend, a wife, something - whatever you like - (and) you will be on the way to knowing more about Him; this is what I say to myself. But one must love with a lofty and serious intimate sympathy, with strength, with intelligence."[5] By 1879, he made a shift in the direction of his life and found he could express his "love of God and man" through painting.[4]

Drawn to Biblical parables, Van Gogh found wheat fields metaphors for humanity's cycles of life, as both celebration of growth and realization of the susceptibility of nature's powerful forces.[6]

- Of the Biblical symbolism of sowing and reaping Van Gogh taught in his Bible lessons: "One does not expect to get from life what one has already learned it cannot give; rather, one begins to see more clearly that life is a kind of sowing time, and the harvest is not here."[7]

- The image of the sower came to Van Gogh in Biblical teachings from his childhood, such as:

The Sower, June 1888, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo. Inspired by Jean-François Millet Van Gogh made several paintings after The Sower by Millet

The Sower, June 1888, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo. Inspired by Jean-François Millet Van Gogh made several paintings after The Sower by Millet

- "A sower went out to sow. As he sowed, some seed fell along the path, and the birds came and devoured it. Other seed fell on rocky ground, where it had not much soil, and immediately it sprang up, since it had no depth of soil; and when the sun rose it was scorched, and since it had no root it withered away. Other seed fell among thorns and the thorns grew up and choked it, and it yielded no grain. And other seeds fell into good soil and brought forth grain, growing up and increasing and yielding thirty fold, and sixty fold and a hundredfold.(Mark 4:3-8)[7]

- Van Gogh used the digger and ploughman as symbols of struggle to reach the kingdom of God.[8]

- He was particularly enamored with "the good God sun" and called anyone who didn't believe in the sun infidels. The painting of the haloed sun was a characteristic style seen in many of his paintings,[9] representing the divine, in reference to the nimbus in Delacroix's Christ Asleep During the Tempest.[10]

- Van Gogh found storms important for their restorative nature, symbolizing "the better times of pure air and the rejuvenation of all society." Van Gogh also found storms to reveal the divine.[11]

Field workers

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

The "peasant genre" that greatly influenced Van Gogh began in the 1840s with the works of Jean-François Millet, Jules Breton, and others. In 1885 Van Gogh described the painting of peasants as the most essential contribution to modern art. He described the works of Millet and Breton of religious significance, "something on high," and described them as the "voices of the wheat."[12]

Throughout Van Gogh's adulthood he had an interest in serving others, especially manual workers. As a young man he served and ministered to coal miners in Borinage, Belgium which seemed to bring him close to his calling of being a missionary or minister to workers.[13]

A common denominator in his favored authors and artists was sentimental treatment of the destitute and downtrodden. Referring to painting of peasants Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: "How shall I ever manage to paint what I love so much?" He held laborers up to a high standard of how dedicatedly he should approach painting, "One must undertake with confidence, with a certain assurance that one is doing a reasonable thing, like the farmer who drives his plow... (one who) drags the harrow behind himself. If one hasn't a horse, one is one's own horse."[13]

Connection to nature

Van Gogh used nature for inspiration, preferring that to abstract studies from imagination. He wrote that rather than making abstract studies: "I am getting well acquainted with nature. I exaggerate, sometime I make change in motif; but for all that, I do not invent the whole picture; on the contrary, I find it already in nature, only it must be disentangled."[14]

The close association of peasants and the cycles of nature particularly interested Van Gogh, such as the sowing of seeds, harvest and sheaves of wheat in the fields.[12] Van Gogh saw plowing, sowing and harvesting symbolic to man's efforts to overwhelm the cycles of nature: "the sower and the wheat sheaf stood for eternity, and the reaper and his scythe for irrevocable death." The dark hours conducive to germination and regeneration are depicted in The Sower and wheat fields at sunset.[12]

In 1889 Van Gogh wrote of the way in which wheat was symbolic to him: "What can a person do when he thinks of all the things he cannot understand, but look at the fields of wheat... We, who live by bread, are we not ourselves very much like wheat... to be reaped when we are ripe."[15]

Van Gogh saw in his paintings of wheat fields an opportunity for people to find a sense of calm and meaning, offering more to suffering people than guessing at what they may learn "on the other side of life."[16][17]

Van Gogh writes Theo that he hopes that his family brings to him "what nature, clods of earth, the grass, yellow wheat, the peasant, are for me, in other words, that you find in your love for people something not only to work for, but to comfort and restore you when there is a need."[18] Further exploring the connection between man and nature, Van Gogh wrote his sister Wil, "What the germinating force is in a grain of wheat, love is in us."[19]

At times Van Gogh was so enamored with nature that his sense of self seemed lost in the intensity of his work: "I have a terrible lucidity at moments, these days when nature is so beautiful, I am not conscious of myself any more, and the picture comes to me as in a dream."[20]

Color

Wheat fields provided a subject in which Van Gogh could experiment with color.[21] Tired of his work in the Netherlands made with dull, gray colors, van Gogh sought to create work that was more creative and colorful.[22] In Paris Van Gogh met leading French artists Edgar Degas, Georges Seurat and others who provided illuminating influences on the use of color and technique. His work, previously somber and dark, now "blazed with color." His use of color was so dramatic that Van Gogh was sometimes called an Expressionist.[23]

While Van Gogh learned much about color and technique in Paris, southern France provided an opportunity to express his "surging emotions."[23] Enlightened by the effects of the sun drenched countryside in southern France, Van Gogh reported that above all, his work "promises color."[24] This is where he began development of his masterpieces.[23]

Van Gogh used complementary, contrasting colors to bring an intensity to his work, which evolved over the periods of his work. Two complementary colors of the same degree of vividness and contrast."[25] Van Gogh mentioned the liveliness and interplay of "a wedding of two complementary colors, their mingling and opposition, the mysterious vibrations of two kindred souls."[26] An example of use of complementary colors is The Sower where gold is contrasted to purple and blue with orange to intensify the impact of the work.[10]

The four seasons were reflected in lime green and silver of spring, yellow when the wheat matured, beige and then burnished gold.[21]

Periods

Nuenen and Paris

Prior to Van Gogh's exploration of southern France, there were just a few of his paintings where wheat was the subject.

The first, Sheaves of Wheat in a Field was painted July–August 1885 in Nuenen, Netherlands.[27] Here the emphasis is on the land and labor is suggested by the "bulging wheat stacks."[28] This work was made several months after The Potato Eaters at a time when he was looking to free himself physically, emotionally and artistically from the gray colors of his art and life, moving away from Nuenen to develop, as author Albert Lubin describes, a more "imaginative, colorful art that suited him much better."[22]

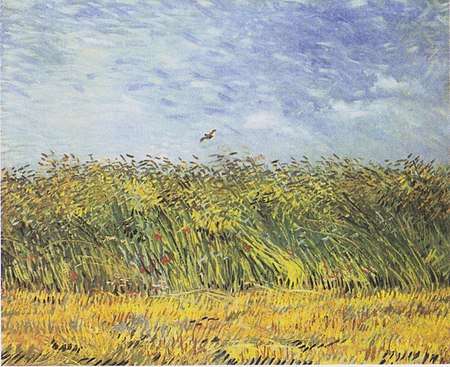

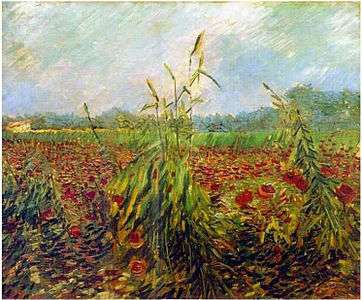

Van Gogh, who "particularly admired a poem written by Walt Whitman about the beauty in a blade of grass", began painting waving stalks of wheat in Paris.[29] In 1887, he made Wheat Field with a Lark where Impressionist influences are reflected in his use of color and management of light and shadow. Brush strokes are made to reflect the objects, like the stalks of wheat.[30][31] The work reflects the motion of the wheat blowing in the wind, the lark flying and the clouds streaking from the currents in the sky. The cycles of life are reflected in the land left by harvested wheat and the growing wheat subject to the forces of the wind, as we are subject to the pressures in our lives. The cycle of life depicted here is both tragic and comforting. The stubble of the harvested wheat reflect the inevitable cycle of death, while the stalks of wheat, flying bird and windswept clouds reflect continual change.[6] Edge of a Wheat Field with Poppies, shown below in black and white, was also painted in 1887.[32]

Edge of a Wheatfield with Poppies, 1887, Private collection (drawing of painting) (F310a)

Edge of a Wheatfield with Poppies, 1887, Private collection (drawing of painting) (F310a)

Arles

Van Gogh was about 35 years of age when he moved to Arles in southern France. There he was at the height of his career, producing some of his best work. His paintings represented different aspects of ordinary life, such as Harvest at La Crau. The sunflower paintings, some of the most recognizable of Van Gogh's paintings, were created in this time. He worked continuously to keep up with his ideas for paintings. This is likely one of Van Gogh's happier periods of life. He is confident, clear-minded and seemingly content.[24]

In a letter to his brother, Theo, he wrote, "Painting as it is now, promises to become more subtle - more like music and less like sculpture - and above all, it promises color." As a means of explanation, Van Gogh explains that being like music means being comforting.[24]

A prolific time, in less than 444 days van Gogh made about 100 drawings and produced more than 200 paintings. Yet, he still found time and energy to write more than 200 letters. While he painted quickly, mindful of the pace farmers would need to work in the hot sun, he spent time thinking about his paintings long before he put brush to canvas.[33]

His work during this period represents a culmination of influences, such as Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism and Japanese art (see Japonism). His style evolved into one with vivid colors and energetic, impasto brush strokes.[34]

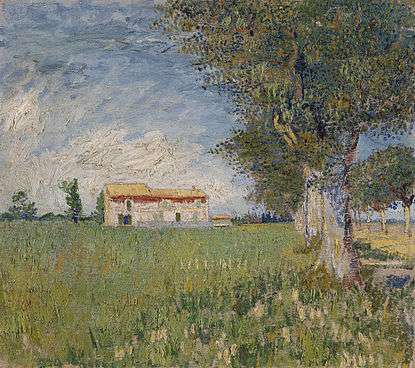

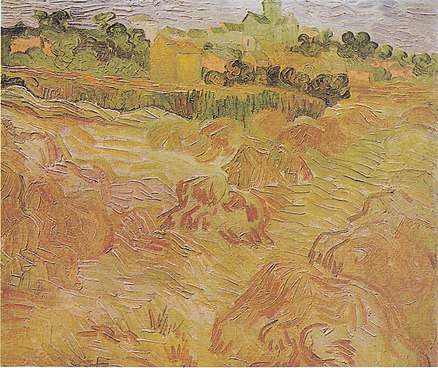

May farmhouses

Both Farmhouse in a Wheat Field[35] and Farmhouses in Wheat Field Near Arles were made in May, 1888[36] which Van Gogh described at the time: "A little town surrounded by fields completely blooming with yellow and purple flowers; you know, it is a beautiful Japanese dream."[37]

Farmhouse in a Wheat Field, May 1888, reportedly at Van Gogh Museum (F408 )

Farmhouse in a Wheat Field, May 1888, reportedly at Van Gogh Museum (F408 ) Farmhouses in Wheat Field Near Arles, 1888, likely at P. and N. de Boer Foundation or Van Gogh Museum, both of which are in Amsterdam, Netherlands (F576 )

Farmhouses in Wheat Field Near Arles, 1888, likely at P. and N. de Boer Foundation or Van Gogh Museum, both of which are in Amsterdam, Netherlands (F576 )

June - The Sower

The audience is drawn into the painting by the glowing disk of the rising Sun in citron-yellow which Van Gogh intended to represent the divine, replicating the nimbus from Eugène Delacroix's Christ Asleep during the Tempest. Van Gogh depicts the cycle of life in the sowing of wheat against the field of mature wheat,[10] there is death, like the setting Sun, but also rebirth. The Sun will rise again. Wheat has been cut, but the sower plants seeds for a new crop. Leaves have fallen from the tree in the distance, but leaves will grow again.[38]

In The Sower, Van Gogh uses complementary colors to bring intensity to the picture. Blue and orange flecks in the plowed field and violet and gold in the spring wheat behind the sower.[10] Van Gogh used colors symbolically and for effect, when speaking of the colors in this work he said: I couldn't care less what the colours are in reality.[39]

Inspired by Jean-François Millet van Gogh made several paintings after The Sower by Millet. Van Gogh made seven other "Sower" paintings, one in 1883 and the other six after this work.[40]

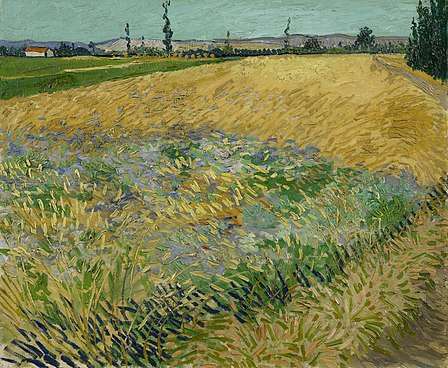

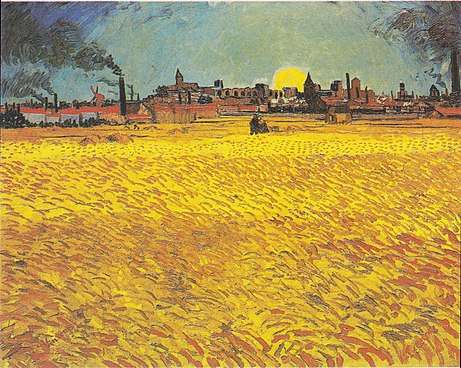

June - Harvest

During the last half of June he worked on a group of ten "Harvest" paintings,[34] which allowed him to experiment with color and technique. "I have now spent a week working hard in the wheatfields, under the blazing sun," Van Gogh wrote on 21 June 1888 to his brother Theo.[41] He described the series of wheat fields as "…landscapes, yellow—old gold—done quickly, quickly, quickly, and in a hurry just like the harvester who is silent under the blazing sun, intent only on the reaping."[33]

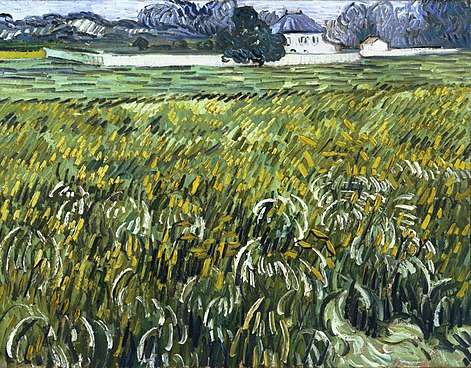

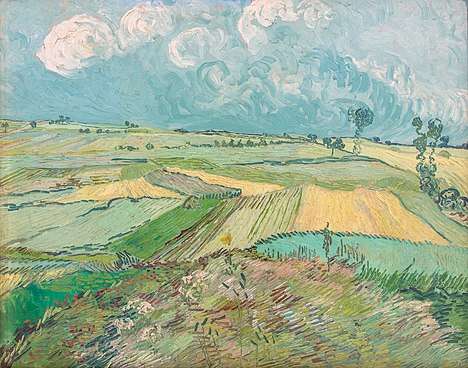

Wheat Fields also Wheat Fields with the Alpilles Foothills in the Background[41] is a view of the vast, spreading plain against a low horizon.[42] Nearly the entire canvas is filled with the wheat field. In the foreground is green wheat of yellow, green, red, brown and black colors, which sets off the more mature, golden yellow wheat. The Alpilles range is just visible in the distance.[41]

Van Gogh wrote about Sunset: Wheat Fields Near Arles: "A summer sun... town purple, celestial body yellow, sky green-blue. The wheat has all the hues of old gold, copper, green-gold or red-gold, yellow gold, yellow bronze, red-green." He made this work during the height of the mistral winds. To prevent his canvas from flying away, van Gogh drove the easel into the ground and secured the canvas to the easel with rope.[43][44]

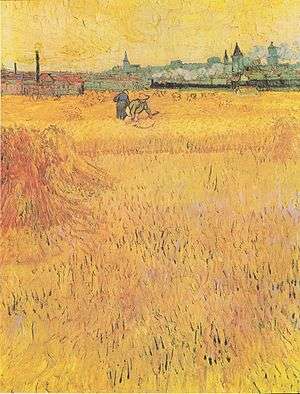

Arles: View from the Wheat Fields (Wheat Field with Sheaves and Arles in the Background), another painting of this series,[45] represents the harvest. In the foreground are sheaves of harvested wheat leaning against one another. The center of the painting depicts the harvesting process.[46]

Wheat Field also Wheat Field with Alpilles Foothills in the Background, June 1888, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F411)

Wheat Field also Wheat Field with Alpilles Foothills in the Background, June 1888, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F411) Sunset: Wheat Fields Near Arles, June 1888, Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Switzerland (F465)

Sunset: Wheat Fields Near Arles, June 1888, Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Switzerland (F465) Arles: View from the Wheat Fields (Wheat Field with Sheaves and Arles in the Background), June 1888, Musée Rodin, Paris, France (F545)

Arles: View from the Wheat Fields (Wheat Field with Sheaves and Arles in the Background), June 1888, Musée Rodin, Paris, France (F545)

Wheat Stacks with Reaper was made in June, 1888 (as indicated by the F number sequence) or[47] June 1890 in Auvers as noted by the Toledo Museum of Art, where it resides. Of the figure "the reaper" Van Gogh expressed his symbolic, spiritual view of those who worked close to nature in a letter to his sister in 1889: "aren’t we, who live on bread, to a considerable extent like wheat, at least aren't we forced to submit to growing like a plant without the power to move, by which I mean in whatever way our imagination impels us, and to being reaped when we are ripe, like the same wheat?"[48]

Harvest in Provence[49] is a particularly relaxed version of the harvest paintings.[50] The painting, made just outside Arles, is an example of how Van Gogh used color in full brilliance[51] to depict "the burning brightness of the heat wave."[52] The painting is also called the Grain Harvest of Provence or Corn Harvest of Provence.

In the foreground of Honolulu Museum of Art's Wheat Field are sheaves of harvested wheat. Horizontal bands mark the wheat fields, behind which are trees and houses on the horizon. His work, like that of his friend Paul Gauguin, that emphasized personal expression over literal composition led to the expressionist movement and towards twentieth-century Modernism.[34]

Wheat Fields or Wheat Fields with Sheaves, June 1888, Honolulu, Honolulu Museum of Art (F561)

Wheat Fields or Wheat Fields with Sheaves, June 1888, Honolulu, Honolulu Museum of Art (F561)

Green Ears of Wheat 1888, Israel Museum, Jerusalem,

Green Ears of Wheat 1888, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Wheat Fields with Stacks 1888 Private collection (no catalog F number, JH 1478)

Wheat Fields with Stacks 1888 Private collection (no catalog F number, JH 1478) Wheat Fields, June 1888, P. and N. de Boer Foundation or Van Gogh Museum(F564)[53]

Wheat Fields, June 1888, P. and N. de Boer Foundation or Van Gogh Museum(F564)[53]

June - complementary harvest paintings

Harvest, named by Van Gogh himself, or Harvest at La Crau, with Montmajour in the Background is made in horizontal planes. The harvested wheat lies in the foreground. In the center the activities for harvest are represented by the haystack, ladders, carts and a man with a pitchfork. The background is purple-blue mountains against a turquoise sky. He was interested in depicting "the essence of country life."[54] In June Van Gogh wrote of the landscape at La Crau that it was "beautiful and endless as the sea." One of his most important works, the landscape reminded him of paintings by 17th century Dutch masters, Ruysdael and Philips Koninck.[43] He also compared this work favorably with his painting The White Orchard.[55]

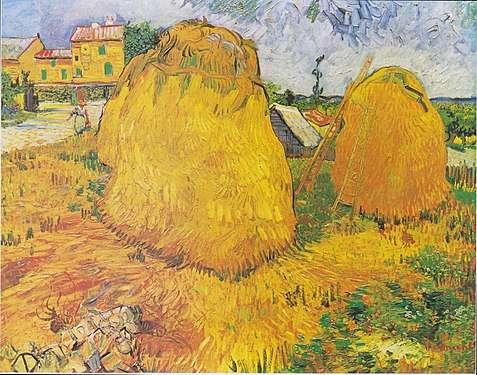

Wheat Stacks in Provence, made about the 12th or 13 June,[56] was intended by Van Gogh to be a complementary work to the Harvest painting.[57] Ladders appear in both paintings which help to create a pastoral feeling.[58]

Harvest or Harvest at La Crau, with Montmajour in the Background, June 1888, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F412)

Harvest or Harvest at La Crau, with Montmajour in the Background, June 1888, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F412) Haystacks near a Farm in Provence, June 1888, Oil on canvas, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F425)

Haystacks near a Farm in Provence, June 1888, Oil on canvas, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F425)

Saint-Rémy

In May 1889, Van Gogh voluntarily entered the asylum[59] of St. Paul[60] near Saint-Rémy in Provence.[61] There Van Gogh had access to an adjacent cell he used as his studio. He was initially confined to the immediate asylum grounds and painted (without the bars) the world he saw from his room, such as ivy covered trees, lilacs, and irises of the garden.[59][62] Through the open bars Van Gogh could also see an enclosed wheat field, subject of many paintings at Saint-Rémy.[63] As he ventured outside of the asylum walls, he painted the wheat fields, olive groves, and cypress trees of the surrounding countryside,[62] which he saw as "characteristic of Provence." Over the course of the year, he painted about 150 canvases.[59]

The Wheat Field

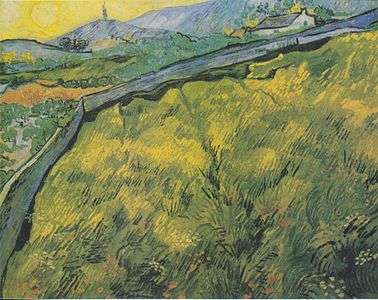

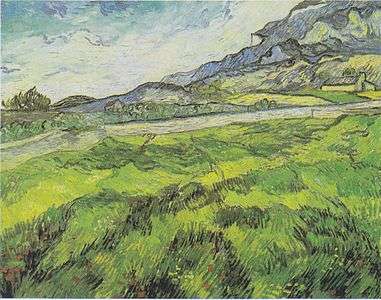

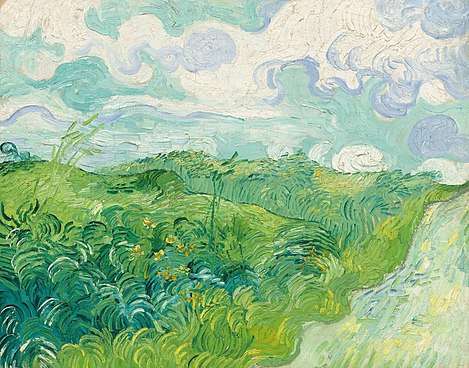

Van Gogh worked on a group of paintings of the wheat field that he could see from his cell at Saint-Paul Hospital. From the studio room he could see a field of wheat, enclosed by a wall. Beyond that were the mountains from Arles. During his stay at the asylum he made about twelve paintings of the view of the enclosed wheat field and distant mountains.[64] In May Van Gogh wrote to Theo, "Through the iron-barred window I see a square field of wheat in an enclosure, a perspective like Van Goyen, above which I see the morning sun rising in all its glory."[65] The stone wall, like a picture frame, helped to display the changing colors of the wheat field.[29]

Green Wheat Field, June 1889, owner unclear, possibly on loan to Kunsthaus Zurich, Zurich (F718)

Green Wheat Field, June 1889, owner unclear, possibly on loan to Kunsthaus Zurich, Zurich (F718) Wheat Field with Reaper and Sun, Late June 1889, Oil on canvas, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F617)

Wheat Field with Reaper and Sun, Late June 1889, Oil on canvas, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F617)

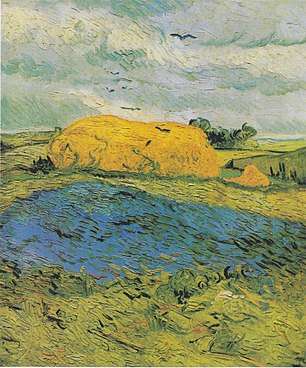

Landscape with Wheat Sheaves and Rising Moon, July 1889, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F735)

Landscape with Wheat Sheaves and Rising Moon, July 1889, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F735) Wheat Field with Reaper, September 1889, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F618)

Wheat Field with Reaper, September 1889, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F618) Rain or Enclosed Wheat Field in the Rain, November 1889, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia (F650)

Rain or Enclosed Wheat Field in the Rain, November 1889, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia (F650)

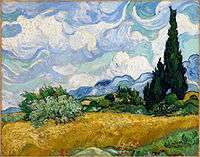

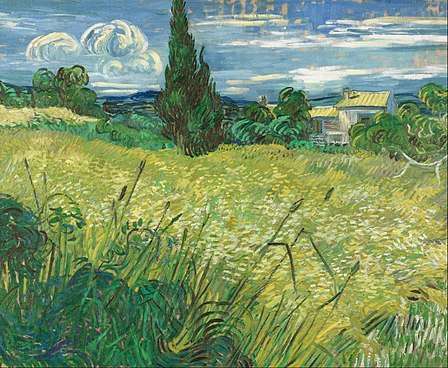

Wheat field with cypresses

The wheat field with cypresses paintings were made when van Gogh was able to leave the asylum. Van Gogh had a fondness for cypresses and wheat fields of which he wrote: "Only I have no news to tell you, for the days are all the same, I have no ideas, except to think that a field of wheat or a cypress well worth the trouble of looking at closeup."[20]

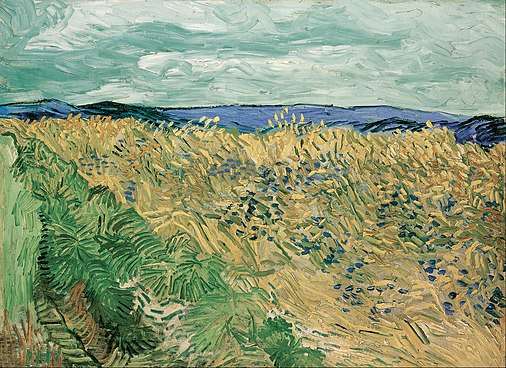

In early July, Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo of a work he began in June, Wheat Field with Cypresses: "I have a canvas of cypresses with some ears of wheat, some poppies, a blue sky like a piece of Scotch plaid; the former painted with a thick impasto . . . and the wheat field in the sun, which represents the extreme heat, very thick too." Van Gogh who regarded this landscape as one of his "best" summer paintings made two additional oil paintings very similar in composition that fall. One of the two is in a private collection.[66]

London's National Gallery A Wheat Field, with Cypresses painting was made in September[67] which author H.W. Janson describes: "the field is like a stormy sea; the trees spring flamelike from the ground; and the hills and clouds heave with the same surge of motion. Every stroke stands out boldly in a long ribbon of strong, unmixed color."[23]

There is also another version of Wheat Fields with Cypresses made in September with a blue-green sky, reportedly held at the Tate Gallery in London (F743).[68]

Other wheat field paintings

Van Gogh describes the ripening Green Wheat Field with Cypress painted in June: "a field of wheat turning yellow, surrounded by blackberry bushes and green shrubs. At the end of the field there is a little house with a tall somber cypress which stands out against the far-off hills with their violet-like and bluish tones, and against a sky the colour of forget-me-nots with pink streaks, whose pure hues form a contrast with the scorched ears, which are already heavy, and have the warm tones of a bread crust."[69]

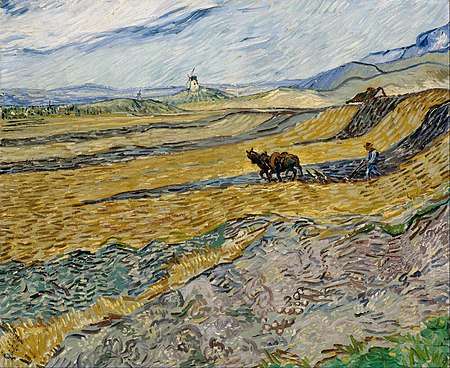

In October Van Gogh made Enclosed Wheat Field with Ploughman.[70]

Green Wheat Field with Cypress, 1889, Narodni Gallery, Prague (F719)

Green Wheat Field with Cypress, 1889, Narodni Gallery, Prague (F719)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Enclosed Field with Peasant, October 1889, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, Indiana

Enclosed Field with Peasant, October 1889, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, Indiana Enclosed Wheat Field with Ploughman, October 1889, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (F706)

Enclosed Wheat Field with Ploughman, October 1889, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (F706)

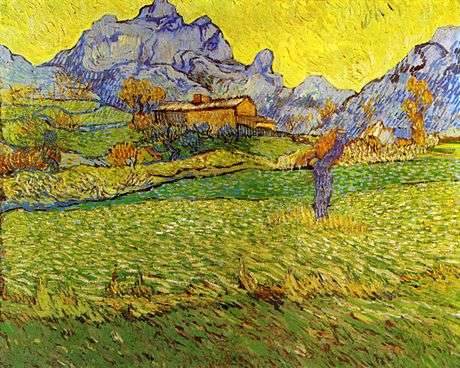

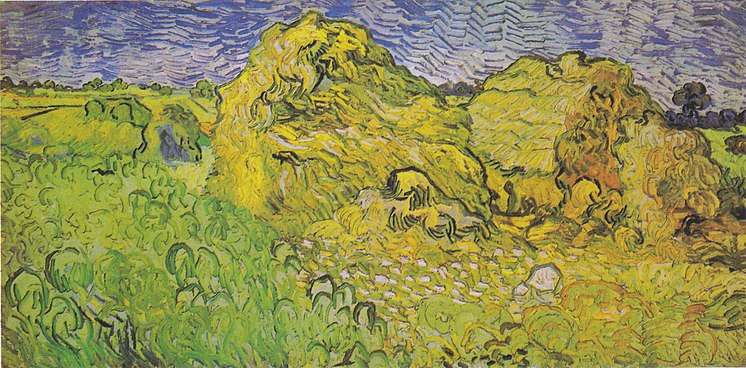

Wheat Fields in a Mountainous Landscape, also titled Meadow in the Mountains was painted in late November - early December 1889.[71]

In November, Wheat Field Behind Saint-Paul was painted by Van Gogh, now owned by Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.[72]

Wheat Fields in a Mountainous Landscape, Late November-Early December 1889, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F721)

Wheat Fields in a Mountainous Landscape, Late November-Early December 1889, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F721) Wheat Field Behind Saint-Paul, November 1889, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia (F722)

Wheat Field Behind Saint-Paul, November 1889, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia (F722)

Auvers-sur-Oise

In May 1890, Van Gogh traveled from Saint-Rémy to Paris,[73] where he had a three-day stay with his brother, Theo, Theo's wife Johanna and their new baby Vincent. Van Gogh found that unlike his past experiences in Paris, he was no longer used to the commotion of the city[43] and was too agitated to paint. His brother, Theo and artist Camille Pissarro developed a plan for Van Gogh to go to Auvers-sur-Oise with a letter of introduction for Dr. Paul Gachet,[73] a homeopathic physician and art patron who lived in Auvers.[74] Van Gogh had a room at the inn Auberge Ravoux in Auvers[43] and was under the care and supervision of Dr. Gachet with whom he grew to have a close relationship, "something like another brother."[43]

For a time, Van Gogh seemed to improve. He began to paint at such a steady pace, there was barely space in his room for all the finished paintings.[73] From May until his death on July 29, Van Gogh made about 70 paintings, more than one a day, and many drawings.."[75] Van Gogh painted buildings around the town of Auvers, such as The Church at Auvers, portraits, and the nearby fields.[43]

Van Gogh arrived in Auvers in late spring as pea plants and wheat fields on gently sloping hills ripened for harvest. The area bustled as migrant workers from France and Brussels descended on the area for the harvest. Partial to rural life, Van Gogh strongly portrayed the beauty of the Auvers country side. He wrote his brother, "I have one study of old thatched roofs with a field of peas in flower in the foreground and some wheat, the background of hills, a study which I think you will like."[76]

Wheat harvest series

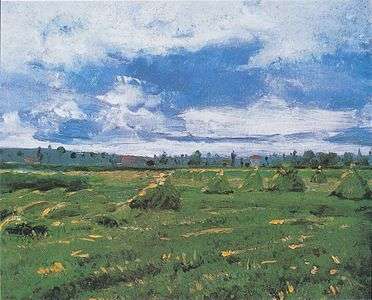

Van Gogh painted thirteen large canvases of horizontal landscapes of the wheat harvest that occurs in the region from the middle to late July. The series began with Wheat Field under Cloudy Sky then Wheatfield with Crows was painted when the crop was on the verge of harvest. Sheaves of Wheat painted after the harvest and concluding with Field with Haystacks (private collection).[77]

Green Wheat Fields or Field with Green Wheat was made in May.[78]

Wheat Field at Auvers with White House[79] was made in June. The painting is mainly a large green field of wheat. In the background is a white house behind a wall and a tree.[80]

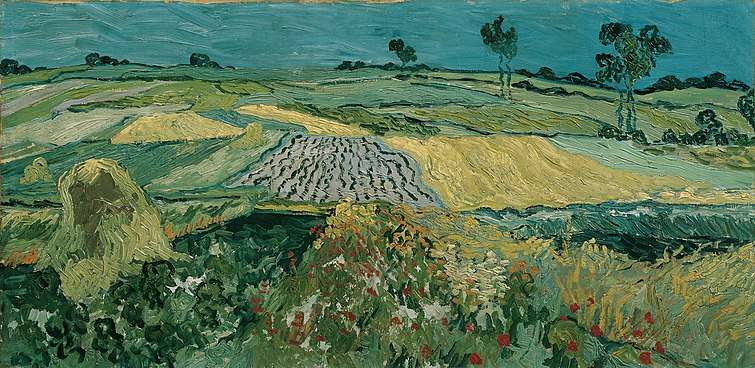

The outlying fields of Auvers, setting for Wheat Fields after the Rain (The Plain of Auvers), form a "zig-zag, patchwork pattern," of yellows, blues, and greens.[81] In the last letter that Van Gogh wrote to his mother he described being very calm, something needed for this work, an "immense plain with wheat fields up as far as the hills, boundless as the ocean, delicate yellow, delicate soft green, the delicate purple of a tilled and weeded piece of ground, with the regular speckle of the green of flowering potato plants, everything under a sky of delicate tones of blue, white, pink and violet."[82] This painting was also called Wheat Fields at Auvers Under Clouded Sky.[83]

Field with Green Wheat, 1890, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (F807)

Field with Green Wheat, 1890, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (F807) Wheat Field at Auvers with White House, June 1890, The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C. (F804)

Wheat Field at Auvers with White House, June 1890, The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C. (F804) Wheat Fields after the Rain (The Plain of Auvers), July 1890, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA (F781)

Wheat Fields after the Rain (The Plain of Auvers), July 1890, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA (F781)

Van Gogh described Ears of Wheat to painter and friend Paul Gauguin as "nothing more than ears of wheat, green-blue stalks long, ribbon-like leaves, under a sheen of green & pink; ears of wheat, yellowing slightly, with an edge made pale pink by the dusty manner of flowering; at the bottom, a pink bindweed winding round a stalk. I would like to paint portraits against a background that is so lively and yet so still." The painting depicts "the soft rustle of the ears of grain swaying back and forth in the wind." He used the motif as the background to a portrait.[84]

The Fields was painted in July and held in a private collection.[85]

An animated Wheatfield with Cornflowers shows the effect of a gust of wind that ripples through the yellow stalks, seeming to "overflow" into the blue background. The heads of a few stalks of wheat seem to have detached themselves, diving into the blue of the hills in the background.[86]

Ears of Wheat, June 1890, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F767)

Ears of Wheat, June 1890, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F767).jpg) The Fields, July 1890, Private Collection (F761)

The Fields, July 1890, Private Collection (F761) Wheat Field with Cornflowers, July 1890, Oil on canvas, 60 x 81 cm, Beyeler Foundation, Riehen, Switzerland (F808)

Wheat Field with Cornflowers, July 1890, Oil on canvas, 60 x 81 cm, Beyeler Foundation, Riehen, Switzerland (F808)

Wheat Fields near Auvers, 1890, owned by Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna[87] was also described by van Gogh as a landscape of the vast wheat fields after a rain.[88]

Van Gogh brings the spectator directly into Sheaves of Wheat by filling the picture plane with eight sheaves of wheat, as if seeing it from a worker's perspective. The sheaves, bathed in yellow light, appear to be recently cut. For contrast, Van Gogh uses the complementary, vivid lavender for shadows and earth in the nearby field.[77]

Wheat Fields near Auvers, 1890, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna (F775)

Wheat Fields near Auvers, 1890, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna (F775) Sheaves of Wheat, 1890, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas. (F771)

Sheaves of Wheat, 1890, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas. (F771)

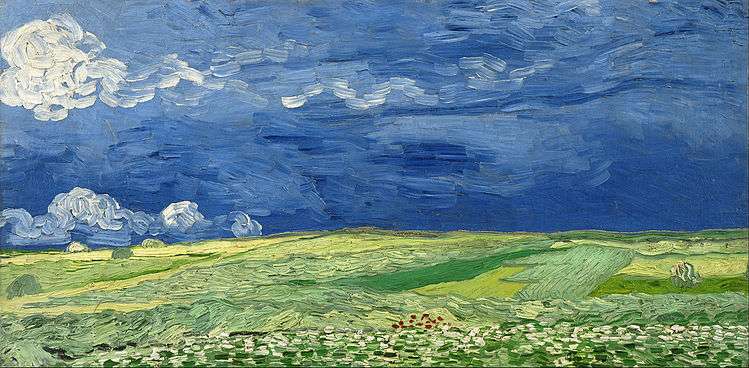

In van Gogh's Wheatfields Under Thunderclouds, also called Wheat Fields Under Clouded Sky, landscape he depicts the loneliness of the countryside and the degree to which it was "healthy and heartening."[89]

The Van Gogh Museum's Wheatfield with Crows was made in July 1890, in the last weeks of Van Gogh's life, many have claimed it was his last work. Others have claimed Tree Roots was his last painting. Wheatfield with Crows, made on an elongated canvas, depicts a dramatic cloudy sky filled with crows over a wheat field.[90] The wind-swept wheat field fills two thirds of the canvas. An empty path pulls the audience into the painting. Jules Michelet, one of Van Gogh's favorite authors, wrote of the crow: "They interest themselves in everything, and observe everything. The ancients, who lived far more completely than ourselves in and with nature, found it no small profit to follow, in a hundred obscure things where human experience as yet affords no light, the directions so prudent and sage a bird." Of making the painting Van Gogh wrote that he did not have a hard time depicting the sadness and emptiness of the painting, which was powerfully offset by the restorative nature of the countryside.[91] Erickson, author of Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision of Vincent van Gogh, cautious of attributing stylistic changes in his work to mental illness, finds the painting expresses both the sorrow and the sense of his life coming to an end.[92] The crows, used by Van Gogh as symbol of death and rebirth or resurrection, visually draw the spectator into the painting. The road, in contrasting colors of red and green, is thought to be a metaphor for a sermon he gave based on Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress where the pilgrim is sorrowful that the road is so long, yet rejoicing because the Eternal City waits at the journey's end.[93]

Wheat Stack Under Clouded Sky also called Haystack under a Rainy Sky, was made July 1890, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F563).[94][95]

Wheatfield Under Thunderclouds, 1890, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F778)

Wheatfield Under Thunderclouds, 1890, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F778) Wheatfield with Crows, July 1890, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F779)

Wheatfield with Crows, July 1890, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F779)

Field with Stacks of Grain, at Beyeler Foundation, Riehen, Switzerland (F809) is one of van Gogh's very last paintings, is both more rigid and at the same time more abstract than other paintings of this series, such as Wheatfield with Cornflowers. Two large stacks of wheat fill the painting like "abandoned buildings," seeming to cut off the sky.[86][96]

Wheat Fields with Auvers in the Background also painted in July is part of the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire collection in Geneva (F801).[97]

Field with Stacks of Grain, July 1890, Beyeler Foundation, Riehen, Switzerland (F809)

Field with Stacks of Grain, July 1890, Beyeler Foundation, Riehen, Switzerland (F809) Wheat Fields with Auvers in the Background, July 1890, Musée d'Art et d'Histoire, Geneva (F801).

Wheat Fields with Auvers in the Background, July 1890, Musée d'Art et d'Histoire, Geneva (F801).

Emotional turmoil

From Wallace,[73] "But for all his appearance of a renewed well-being his life was very near its end." Illness struck Theo's baby, Vincent. Theo had both health and employment issues; he considered leaving his employer and starting his own business. Gachet, said to have his own eccentricities and neurosis, caused van Gogh concern to which he questioned: "Now when one blind man leads another blind man, don't they both end up in the ditch?"[43][73]

After visiting Paris for a family conference, Van Gogh returned to Auvers feeling more bleak. In a letter he wrote, "And the prospect grows darker, I see no future at all."[73]

He later had a period where he said that "the trouble I had in my head has considerably calmed...I am completely absorbed in that immense plain covered with fields of wheat against the hills boundless as the sea in delicate colors of yellow and green, the pale violet of the plowed and weeded earth checkered at regular intervals with the green of the flowering potato plants, everything under a sky of delicate blue, white, pink, and violet. I am almost too calm, a state that is necessary to paint all that."

Four days after completing Wheat Fields after the Rain he shot himself in the Auvers wheat fields. Van Gogh died on July 29, 1890.[81]

References

- Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-8294-0621-2.

- Wallace, R (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books. p. 37.

- Mancoff, D (1999). Van Gogh's Flowers. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-7112-2908-2.

- Van Gogh, V & Leeuw, R (1997) [1996]. van Crimpen, H & Berends-Albert, M. (eds.). The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London and other locations: Penguin Books.

- Wallace (1969). of Time-Life Books (ed.). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA: Time=Life Books. pp. 12–15.

- Maurer, N; van Gogh, V; Gauguin, P (1999) [1998]. The Pursuit of Spiritual Wisdom: The Thought and Art of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Canbury and other locations: Associated University Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-8386-3749-3.

- Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent Van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. p. 33,96. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent Van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. p. 97. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- Lubin, A (1996) [1972]. Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh. United States: De Capo Press. p. 221. ISBN 0-306-80726-2.

- Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent Van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. p. 99. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola Press. p. 147. ISBN 0-8294-0621-2.

- van Gogh, V, van Heugten, S, Pissarro, J, Stolwijk, C (2008). Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night. Brusells: Mercatorfonds with Van Gogh Museum and Museum of Modern Art. pp. 12, 25. ISBN 978-0-87070-736-0.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Wallace, R (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books. pp. 10, 14, 21, 30.

- Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 0-8294-0621-2.

- "Landscape at Saint-Rémy (Enclosed Field with Peasant)". Collection. 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola Press. p. 111. ISBN 0-8294-0621-2.

- Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh Saint-Rémy, 2 July 1889". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits (funded in part by U.S. Department of Education, Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education). Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- Van Gogh, V & Leeuw, R (1997) [1996]. van Crimpen, H & Berends-Albert, M. (eds.). The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London and other locations: Penguin Books. p. F605.

- Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-8294-0621-2.

- Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola Press. p. 102. ISBN 0-8294-0621-2.

- Fell, D (2001). Van Gogh's Gardens. United Kingdom: Simon & Schuster. p. 43. ISBN 0-7432-0233-3.

- Lubin, A (1996) [1972]. Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh. United States: De Capo Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 0-306-80726-2.

- H. W. Janson (1971). "The Modern World". A Basic History of Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 308. ISBN 0-13-389296-4.

- Morton, M; Schmunk, P (2000). The Arts Entwined: Music and Painting in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 177–178. ISBN 0-8153-3156-8.

- Fell, D (2005) [2004]. Van Gogh's Women: Vincent's Love Affairs and Journey Into Madness. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 64. ISBN 0-7867-1655-X.

- Silverman, D (2000). Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Search for Sacred Art. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 326. ISBN 0-374-28243-9.

- "Sheaves of Wheat in a Field". Collection. Kröller-Müller Museum. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-520-08849-8.

- Fell, D (2001). Van Gogh's Gardens. United Kingdom: Simon & Schuster. p. 40. ISBN 0-7432-0233-3.

- "Wheat Field with a Lark". Van Gogh Gallery. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Wallace, R (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books. p. 49.

- "Edge of a Wheat Field with Poppies". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- "Effects of the Sun in Provence" (PDF). National Gallery of Art Picturing France (1830-1900). Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art: 18.

- "Wheat Field". Collection. Honolulu Academy of Art. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Farmhouse in a Wheat Field". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ":Farmhouses in Wheat Field Near Arles". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Arles, 12 May 1888". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits (funded in part by U.S. Department of Education, Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education). Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- Lubin, A (1996) [1972]. Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh. United States: De Capo Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-306-80726-2.

- Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Emile Bernard Arles, c. 18 June 1888". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits (funded in part by U.S. Department of Education, Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education). Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- "Van Gogh Catalog". Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 10, 2011enter "sower" in the name field and "p" in the type field.

- "Wheat Fields". Collection. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- Mancoff, D (1999). Van Gogh's Flowers. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7112-2908-2.

- Van Gogh, V & Leeuw, R (1997) [1996]. van Crimpen, H & Berends-Albert, M. (eds.). The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London and other locations: Penguin Books. p. F497.

- "Sunset: Wheat Fields near Arles". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- "Arles: View from the Wheat Fields". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ten-Doesschate Chu, P (2006) [2002]. Nineteenth-Century European Art. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 436. ISBN 0-13-188643-6.

- "Wheat Stacks with Reaper". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- "Wheat Field with Reapers, Auvers" (PDF). Collection. Toledo Museum of Art. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- "Harvest in Provence". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- Hansen, Nichols, Sund, Knudsen, Bremen (2003). Van Gogh: Fields. Hatje Cantz Publishers for Toledo Museum of Art Exhibition. p. 32. ISBN 3-7757-1131-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Israel Museum (1971). The Israel Museum: A Brief Guide. Jerusalem. p. 34.

- Barrielle, J-F (1984). La vie et l'œuvre de Vincent van Gogh. p. 120. ISBN 978-2-86770-003-3.

- "Wheat Fields". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- "The Harvest, 1888". Collection. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh Arles, 12 or 13 June 1888". Webexhibits. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- "Wheat Stacks in Provence". Collection. Kröller-Müller Museum. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Silverman, D (2000). Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Search for Sacred Art. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 444. ISBN 978-0-374-52932-1.

- Fell, D (2001). Van Gogh's Gardens. United Kingdom: Simon & Schuster. p. 96. ISBN 0-7432-0233-3.

- "Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". Thematic Essay, Vincent van Gogh. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- "Olive Trees, 1889, van Gogh". Collection. Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- "Olive Trees, 1889, Van Gogh". Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- "The Therapy of Painting". Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- Van Gogh, V & Leeuw, R (1997) [1996]. van Crimpen, H & Berends-Albert, M. (eds.). The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London and other locations: Penguin Books. p. F604.

- "Rain". Collections. Philadelphia Museum of Art. 2011. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-8294-0621-2.

- "Wheat Field with Cypresses". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2011. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "A Wheat Field, with Cypresses". Collection, Vincent van Gogh. National Gallery, London. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Wheat Field with Cypresses". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. 2011. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Wilhelmina van Gogh, Saint-Rémy, 16 June 1889". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits (funded in part by U.S. Department of Education, Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education). Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- "Enclosed Wheat Field with Ploughman". Collections. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Wheat Fields in a Mountainous Landscape". Collection. Kröller-Müller Museum. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Wheat Field Behind Saint-Paul". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- Wallace, R (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books. pp. 162–163.

- Strieter, T (1999). Nineteenth-Century European Art: A Topical Dictionary. Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-313-29898-X.

- "Girl in White, 1890". The Collection. National Gallery of Art. 2011. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- Leaf, A; Lebain, F (2001). Van Gogh's Table: At the Auberge Ravoux. New York: Artisan. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-57965-315-6.

- "Sheaves of Wheat". Collections. Dallas Museum of Art. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- "Green Wheat Fields". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- "Wheat Field at Auvers with White House". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Wilhelmina van Gogh, Auvers-sur-Oise, c. 12 June 1890". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits (funded in part by U.S. Department of Education, Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education). Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- "Wheat Fields after the Rain (The Plain of Auvers)". Explore the Collection. Carnegie Museum of Art. 2007. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to His Parents, Auvers-sur-Oise, c. 10-14 July 1890". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits (funded in part by U.S. Department of Education, Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education). Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- "Wheat Fields at Auvers Under Clouded Sky". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- "Ears of Wheat". Collection. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- "The Fields". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- "Vincent van Gogh". Collection. Fondation Beyeler. 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Wheat Fields near Auvers". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Auvers-sur-Oise, 23 July 1890". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits (funded in part by U.S. Department of Education, Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education). Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- "Wheatfields under Thunderclouds". Collection. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- "Wheatfield with Crows". Collection. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola Press. pp. 78, 186. ISBN 0-8294-0621-2.

- Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent Van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. pp. 103, 148. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent Van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. pp. 162–163. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- "Haystacks Under a Rainy Sky". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- "Wheat Stack Under a Cloudy Sky". Kröller-Müller Museum. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- "Field with Stacks of Grain". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- "Wheat Fields with Auvers in the Background". Van Gogh Paintings. Van Gogh Gallery. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

External links

- Van Gogh, paintings and drawings: a special loan exhibition, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, which contains material on these paintings (see index)