Early works of Vincent van Gogh

The early works of Vincent van Gogh comprise a group of paintings and drawings that Vincent van Gogh made when he was 27 and 28, in 1881 and 1882, his first two years of serious artistic exploration. Over the course of the two-year period Van Gogh lived in several places. He left Brussels, where he had studied for about a year in 1881, to return to his parents’ home in Etten (North Brabant), where he made studies of some of the residents of the town. In January 1882 Van Gogh went to The Hague where he studied with his cousin-in-law Anton Mauve and set up a studio, funded by Mauve. During the ten years of Van Gogh's artistic career from 1881 to 1890 Vincent's brother Theo would be a continuing source of inspiration and financial support; his first financial support began in 1880 funding Vincent while he lived in Brussels.

| The Sower (after Millet) | |

|---|---|

_F_830_JH_1.jpg) | |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | 1881 |

| Type | Pen and watercolor on paper |

| Dimensions | 48.1 cm × 36.7 cm (18.9 in × 14.4 in) |

| Location | Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands |

In 1882 Van Gogh had an offer for a commission of paintings of The Hague however the paintings, now considered masterpieces, were not acceptable. Van Gogh started out primarily drawing and painting with watercolor. Under Mauve's tutelage Van Gogh began painting with oils in 1882. A subject that fascinated Van Gogh was the working class or peasant, inspired by the works of Jean-François Millet and others.

Background

Early adulthood

In July 1869, Van Gogh's uncle, “Cent” Van Gogh, helped him obtain a position with the art dealer Goupil & Cie in The Hague. After his training, in June 1873, Goupil transferred him to London, where he lodged at 87 Hackford Road, Brixton,[1] and worked at Messrs. Goupil & Co., 17 Southampton Street.[2] This was a happy time for him; he was successful at work and was, at 20, earning more than his father. He fell in love with his landlady's daughter, Eugénie Loyer, who rejected him. He was increasingly isolated and fervent about religion. His father and uncle sent him to Paris to work in a dealership. However, he became resentful at how art was treated as a commodity, a fact apparent to customers. On 1 April 1876, his employment was terminated.[3]

Van Gogh explored his interest in ministry to serve working people.[4][5] He studied for a time in the Netherlands but his zeal and self-imposed asceticism cost him a short-term position in lay ministry. He became somewhat embittered and rejected the church establishment, yet found a personal spirituality that was comforting and important to him.[5] By 1879, he made a shift in the direction of his life and found he could express his "love of God and man" through painting.[4]

In 1880 Van Gogh writes of his desire to be useful as an artist, "To try to understand the real significance of what the great artists, the serious masters, tell us in their masterpieces, that leads to God; one man wrote or told it in a book; another, in a picture." After having moved to Brussels Van Gogh decided to study on his own, rather than at the art academy, often in the company of Dutch artist Anthon van Rappard. It is at this point his brother Theo, working as an art dealer at the Paris Goupil & Cie branch, began sending him money for support, a practice that continued throughout the brother's lives.[6]

Etten, Drenthe and The Hague

In April 1881, Van Gogh moved to the Etten (Noord-Brabant) countryside in the Netherlands with his parents where he continued drawing, often using neighbors as subjects. Through the summer he spent much time walking and talking with his recently widowed cousin, Kee Vos-Stricker. She was the daughter of his mother's older sister and Johannes Stricker, who had shown warmth towards the artist.[7] Although Van Gogh would have liked to marry Stricker, given her decisive refusal: "No, never, never" (niet, nooit, nimmer)[8] and his inability to support himself financially, marriage was out of the question.[9] Van Gogh was hurt deeply. That Christmas he quarreled violently with his father, to the point of refusing a gift of money, and left for The Hague.[10]

In January 1882, he settled in The Hague where he called on his cousin-in-law, the painter Anton Mauve (1838–88). Mauve introduced him to painting in both oil and watercolor and lent him money to set up a studio;[11] however the two soon fell out, possibly over the issue of drawing from plaster casts.[12] Mauve appears to have suddenly gone cold towards Van Gogh and did not return a number of his letters,[13] Van Gogh supposed that Mauve did not approve of his domestic arrangement with an alcoholic prostitute, Clasina Maria "Sien" Hoornik (1850–1904)[14] and her young daughter.[15][16] He had met Sien towards the end of January,[17] when she had a five-year-old daughter and was pregnant.[18] On 2 July, Sien gave birth to a baby boy, Willem.[19] Van Gogh's father put considerable pressure on his son to abandon Sien and her children.[20] Vincent was at first defiant in the face of opposition.[21]

Van Gogh's art dealer uncle, Cornelis, commissioned 20 ink drawings of the city, which the artist completed by the end of May.[22] That June, he spent three weeks in a hospital suffering from gonorrhea.[23] That summer he began to paint in oil.[24] In autumn 1883, after a year together, he left Sien and the two children.[25] Van Gogh moved to the Dutch province of Drenthe, in the northern Netherlands. That December, driven by loneliness, he went to stay with his parents who were by then living in Nuenen, North Brabant.[26]

Development as an artist

Van Gogh drew and painted with watercolors while at school; few of these works survive and authorship is challenged on some of those that do.[27] When he committed to art as an adult, he began at an elementary level by copying the Cours de dessin, edited by Charles Bargue and published by Goupil & Cie. Within two years he had begun to seek commissioned. In Spring 1882, his uncle, Cornelis Marinus - owner of a renowned gallery of contemporary art in Amsterdam - asked him for drawings of the Hague. Van Gogh's work did not prove equal to his uncle's expectations. Marinus offered a second commission, this time specifying the subject matter in detail, but was once again disappointed with the result. Nevertheless, Van Gogh persevered. He improved the lighting of his studio by installing variable shutters and experimented with a variety of drawing materials. For more than a year he worked on single figures —highly elaborated studies in "Black and White",[28] which at the time gained him only criticism. Today, they are recognized as his first masterpieces.[29]

Peasant genre

The "peasant genre" related to the Realism movement that greatly influenced Van Gogh began in the 1840s with the works of Jean-François Millet, Jules Breton, and others. He described the works of Millet and Breton of religious significance, "something on high," and described them as the "voices of the wheat."[30]

Throughout Van Gogh's adulthood he had an interest in serving others, especially manual workers. As a young man he served and ministered to coal miners in Borinage, Belgium which seemed to bring him close to his calling of being a missionary or minister to workers.[31]

A common denominator in his favored authors and artists was sentimental treatment of the destitute and downtrodden. Referring to painting of peasants Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: "How shall I ever manage to paint what I love so much?" He held laborers up to a high standard of how dedicatedly he should approach painting, "One must undertake with confidence, with a certain assurance that one is doing a reasonable thing, like the farmer who drives his plow... (one who) drags the harrow behind himself. If one hasn't a horse, one is one's own horse."[31]

In 1885 Van Gogh described the painting of peasants as the most essential contribution to modern art.[30] See also Peasant Character Studies (Van Gogh series).

The works

1881

Crouching Boy with Sickle, Black chalk and watercolor

Crouching Boy with Sickle, Black chalk and watercolor

1881

Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F851)

1882

On a blustery day, Van Gogh set up his easel and painted "plein-air" (in the open air) at a beach resort, Scheveningen, near The Hague to paint View of the Sea at Scheveningen (F4). While Impressionists are often given credit for painting outdoors, they were not the first to do so. Most, however, made sketches on the spot and worked on the painting in a studio. In this case, Van Gogh struggled with the strong wind which sent grains of sand into his thickly applied paint. Although most of the sand was scraped off, there are still a few grains of sand enmeshed in the layers of paint.[32] The tumultuous weather is well depicted with white-capped seas, threatening sky and wind-blown flags. This painting was stolen from the Van Gogh Museum in December 2002 and discovered in Naples, Italy in September 2016.[33][34]

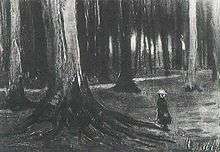

Of a study that Van Gogh made for Girl in a Wood or Girl in White in the Woods, (F8)[35] he remarked at how much he enjoyed the work and explains how he wishes to trigger the audience's senses and how they may experience the painting: "The other study in the wood is of some large green beech trunks on a stretch of ground covered with dry sticks, and the little figure of a girl in white. There was the great difficulty of keeping it clear, and of getting space between the trunks standing at different distances - and the place and relative bulk of those trunks change with the perspective - to make it so that one can breathe and walk around in it, and to make you smell the fragrance of the wood."[36]

In The Girl in the Woods (F8a) the girl is overshadowed by the immense oak trees. The painting may be reminiscent for Van Gogh of the times in his youth he fled to the Zundert Woods to escape from his family.[37]

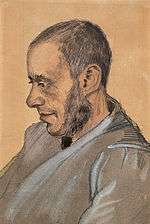

In November 1882 Van Gogh began drawings of individuals to depict a range of character types from the working class, Worn Out was one of the series. The works were drawn in a black in an angular style.[38] On November 24, 1882 Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo of Adrianus Zuyderland, the man who posed for Worn Out (F997), "What a fine sight an old working man makes, in his patched bombazine suit with his bald head". Zuyderland was resident of the Dutch Protestant Almshouse for Old Men and Women. Van Gogh would offer a small payment for residents who would pose for him. On his pencil drawings, Van Gogh used milk as a fixative to counteract the graphite pencil shine and left the image "velvety black". While it was recommended to use an atomizer to control the amount of milk placed on the work, Van Gogh would pour an entire glass of milk on the work. In this drawing there is a noticeable stain around the drawing where the puddle of milk dried. Worn Out is not displayed on this page, but can be found on the Van Gogh Museum website.[39]

Unlike the character studies Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo in November 1882 that he had drawn a portrait of Jozef Blok (F993), a street bookseller who was sometimes called "Binnenhof's outdoor librarian". The work was detailed in pencil with watercolor and chalk. At this time it was rare for Van Gogh to use color, as he found it difficult to work with.[38]

Beach at Scheveningen in Calm Weather, oil on paper on wood

Beach at Scheveningen in Calm Weather, oil on paper on wood

1882

Private collection (F2), displayed in the Minnesota Maritime Art Museum Dunes

Dunes

1882

Private collection (F2a) Dunes with Figures

Dunes with Figures

1882

Private Collection (F3)

Cluster of Old Houses with the New Church in The Hague

Cluster of Old Houses with the New Church in The Hague

1882

Private collection (F204) The Iron Mill in The Hague, watercolor

The Iron Mill in The Hague, watercolor

1882

Private collection (F926) Meadows near Rijswijk, watercolor

Meadows near Rijswijk, watercolor

1882

Private collection (F927) Rooftops, View from the Atelier, watercolor with white

Rooftops, View from the Atelier, watercolor with white

1882

Private collection (F943) Bleaching Ground at Scheveningen also Bleaching Ground, watercolor

Bleaching Ground at Scheveningen also Bleaching Ground, watercolor

1882

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (F946r).jpg) Pollard Willow, watercolor

Pollard Willow, watercolor

1882

Private collection (F947).jpg)

The Potato Market, watercolor

The Potato Market, watercolor

1882

Private collection (F1091)_12_1-4_x_9_7-16in._(31_x_24cm).jpg) Two Women in the Woods

Two Women in the Woods

1882

Private Collection (F1665).jpg) Annotated by the artist in ink at lower left: "At Eternity's gate" (lithograph, 1882, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art)[40] (F1662)

Annotated by the artist in ink at lower left: "At Eternity's gate" (lithograph, 1882, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art)[40] (F1662)

See also

Resources

References

- Hackford Road, UK: Vauxhall Society, archived from the original on 2007-09-27, retrieved 27 June 2009.

- Letter 7 Vincent to Theo, 5 May 1873.

- Tralbaut (1981), 35–47

- Leeuw, R (1997) [1996]. van Crimpen, H; Berends-Albert, M (eds.). The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. London and other locations: Penguin Books.

- Wallace (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books. pp. 12–15.

- "Art and Faith". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- Erickson (1998), 5

- Letter 153 Vincent to Theo, 3 November 1881

- Gayford (2006), 130–1.

- Letter 166 Vincent to Theo, 29 December 1881

- "Letter 196". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- "Letter 219". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- Tralbaut (1981), 96–103

- Callow (1990), 116; cites the work of Hulsker.

- Callow (1990), 123–124

- "Letter 224". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- Callow (1990), 117

- Callow (1990), 116; citing the research of Jan Hulsker; the two dead children were born in 1874 and 1879.

- Tralbaut (1981), 107

- Callow (1990), 132

- Tralbaut (1981),102–104,112

- Letter 203 Vincent to Theo, 30 May 1882 (postcard written in English)

- Letter 206, Vincent to Theo, 8 June or 9, June 1882

- Tralbaut (1981),110

- Arnold, 38

- Tralbaut (1981), 111–122

- Van Heugten (1996), 246–251: Appendix 2—Rejected works

- Artists working in Black & White, i. e. for illustrated papers like The Graphic or Illustrated London News were among Van Gogh's favorites. See Pickvance (1974/75)

- See Dorn, Keyes & alt. (2000)

- van Gogh, V; van Heugten, S; Pissarro, J; Stolwijk, C (2008). Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night. Brusells: Mercatorfonds with Van Gogh Museum and Museum of Modern Art. pp. 12, 25. ISBN 978-0-87070-736-0.

- Wallace, R (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books. pp. 10, 14, 21, 30.

- "Plein-air Painting". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- "View of the Sea at Scheveningen, 1882". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- "Twee gestolen schilderijen Van Gogh na veertien jaar teruggevonden" (in Dutch), de Volkskrant, 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- "Girl in a wood". Collection. Kröller-Müller Museum. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- van Gogh, V (2011). Harrison, R (ed.). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, The Hague, 20 August 1882". Letters of Vincent van Gogh. Translated by van Gogh, J. WebExhibits. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- Lubin, A (1996) [1972]. Stranger on the Earth: A Psychological Biography of Vincent van Gogh. Da Capo Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 0-306-80726-2.

- "Portrait of Jozef Blok, 1882". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-10' See also "More information", "Exceptional Portrait" on the same page

- "Worn Out, 1882". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-10' See more information

- "At Eternity's Gate", vggallery.com. Last Retrieved 19 October 2011.

Bibliography

- Callow, Philip. Vincent van Gogh: A Life, Ivan R. Dee, 1990. ISBN 1-56663-134-3.

- Dorn, Roland, Keyes, George S. & alt. Van Gogh Face to Face — The Portraits (exh. cat). Detroit, Boston & Philadelphia, 2000–01, Thames & Hudson, London & New York, 2000. ISBN 0-89558-153-1

- Erickson, Kathleen Powers. At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision of Vincent van Gogh, 1998. ISBN 0-8028-4978-4.

- Gayford, Martin. "The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles". Penguin, 2006. ISBN 0-670-91497-5.

- Pomerans, Arnold. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. Penguin Classics, 2003. ISBN 0-14-044674-5

- Tralbaut, Marc Edo. Vincent van Gogh, le mal aimé. Edita, Lausanne (French) & Macmillan, London 1969 (English); reissued by Macmillan, 1974 and by Alpine Fine Art Collections, 1981. ISBN 0-933516-31-2.

- van Heugten, Sjraar. Van Gogh The Master Draughtsman. Thames and Hudson, 2005. ISBN 978-0-500-23825-7.

Literature

- Vincent van Gogh: Drawings, ed. Johannes van der Wolk, Ronald Pickvance & E. B. F. Pey, Arnoldo Mondadori Arte & De Luca Edizione d'Arte 1990 (editions in various languages: ISBN 88-242-0024-9 (Dutch))

- Vincent van Gogh: The Drawings, ed. Colta Ives, Susan Alyson Stein etc., The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York & Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2005 ISBN 1-58839-164-7

External links

- Van Gogh Museum, Van Gogh Early Works - to 1886

- Van Gogh, paintings and drawings: a special loan exhibition, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, which contains material on these early works (see index)