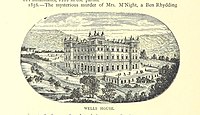

Wells House, Ilkley

Wells House is a large former hydropathic establishment and hotel in Ilkley, West Yorkshire, England, now used as private apartments. It was built in 1854–56 to a design by the architect Cuthbert Brodrick and is a Grade II listed building. It is located above the town on Wells Road at the edge of Ilkley Moor, giving it an unobstructed view across Wharfedale from its north front. It was originally set in grounds by the landscaper Joshua Major though these gardens have mostly been built on since.

| Wells House | |

|---|---|

Wells House from the south west | |

| |

| Former names | Wells Hydro Ilkley College of Education |

| General information | |

| Type | Hydropathic establishment / hotel |

| Architectural style | Italianate |

| Town or city | Ilkley, West Yorkshire |

| Coordinates | 53.9200°N 1.8262°W |

| Opened | 28 May 1856 |

| Renovated | 2001–03 |

| Cost | £30,000[1] |

| Renovation cost | £7.5 million[2] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Cuthbert Brodrick |

| Designations | |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Designated | 20 May 1976 |

| Reference no. | 1133469 |

Wells House possesses a monumental and sombre character, constructed in dark local stone using an Italianate style influenced by the work of John Vanbrugh and Charles Barry. Brodrick's biographer Derek Linstrum described it as a "miniature Blenheim Palace".[3] Its original health purpose was to offer cold baths and water treatments, which were popular in the 19th century when Ilkley was a fashionable and affluent spa resort. After closure of the hydropathic establishment in the 1880s, it was used as a hotel, as a further education college from 1952, and was converted into 24 luxury apartments in 2003.[4]

History

Ilkley's first hydropathic establishment was built at Ben Rhydding in 1843-4 in a Scottish baronial style to exploit the supposed health-giving properties of the town's waters. Well-off people with rheumatic and arthritic aches and pains paid to be immersed in hot and cold baths in an alternative medicine known as hydrotherapy, resulting in the construction of hydros in the mid-century and "spa-tourism".

A group of Bradford businessmen, led by Benjamin Briggs Popplewell, formed the Wells House Hydropathic Company and acquired land,[5] and in February 1854, commissioned the Hull-born and Leeds-based Cuthbert Brodrick to design their building. He was occupied with the construction of Leeds Town Hall but took on the Ilkley commission concurrently. It came at a cost of more than £30,000 (equivalent to £2,824,000 in 2019) and was completed by 1856, opening on 28 May.[1] Because of its isolated, moorside location, Wells House is the only building by Brodrick known to have been surrounded by a designed landscape, the work of Joshua Major (1787–1856), a Yorkshire landscape gardener.[6]

The most famous visitor to the Wells House Hydro was the naturalist Charles Darwin, who stayed with his family in October 1859. He undertook the "water cure" as well as walks on the Moor. Due to the unusually early winter, his daughter Henrietta described their stay as "a time of frozen misery". The family left Ilkley on 24 November, the day of publication of his work On the Origin of Species. Darwin finally left for London on 7 December, a stay of almost nine weeks.[7]

By the 1880s, hydrotherapy began to decline as the benefits of the treatment were discredited. The building subsequently found a new use as a hotel for the next seventy years; this featured a Winter Gardens with sprung dance-floor, raised bandstand, and a 3-span roof supported by decorative arched cast-iron trusses built on top of the terrace.[8] The impact of two world wars saw the hotel's closure.[4]

The local authority took over the building and opened the Ilkley College of Housecraft in 1952, with parts of the grounds being developed to provide additional accommodation for the college over following years. Known as the "pud school", the institution became Ilkley College of Education and then merged with Bradford College to form Bradford and Ilkley College.[4] The site (including ancillary buildings) which contained around 100 staff and 400 students, was considered too expensive to run and it was closed and sold in 1999.[9] Later building additions were removed and the building and the surrounding site were scheduled for residential development.[4]

Wells House is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a Grade II listed building, having been designated on 20 May 1976.[10] Grade II is the lowest of the three grades of listing, and is applied to "buildings that are nationally important and of special interest".[11] It also sits within the Ilkley Conservation Area.[8]

The building was refurbished and converted into apartments between 2001–03 by the developer Magellan Residential, retaining some gardens to the north and west while residential properties occupy the rest of its grounds.[4] The £7.5 million refurbishment, which centered the flats around a new glazed atrium in place of the courtyard, won Bradford District Design Award 2004 for Best Residential Conversion, RICS Pro-Yorkshire for Best Residential Scheme 2003 and the Ilkley Civic Society Award for Conservation 2003.[2]

Description

Wells House has a generally symmetrical square design around an inner courtyard, with the building's main entrance to the south. It has three 9-bay storeys, and projecting 2-bay towers on each corner which add an attic storey, and which are each topped with four small cupolas and spires. The style of window varies by floor; segmental arches on the ground, round-headed with Gibbs surrounds on the first, and a surround of grooved pilaster strips on the second floor. The attic windows come in groups of three round-headed windows flanked by composite pilasters and separated by composite columns.[10] Unusually, all windows retain their original timber sashes, with different pane sizes and patterns to each floor.[8]

The masonry of the facade is richly textured and detailed; the ground storey and tower corners are faced with the "astrakhan"-type vermiculation used on parts of the Louvre,[1] and smooth-faced ashlar walls to the upper storeys. An arched central doorway has a deeply recessed surround and carved keystone head.

Internally, the accommodation was spacious, featuring a hall with a cantilevered stair at each end with cast-iron balusters of unusual design using geometric shapes.[8] The interior was described as:

A noble dining room, calculated to dine comfortably from 80 to 100 guests, a large general public drawing room, a private drawing room for ladies only, a coffee room for general visitors, or those not wishing to join the company at the table d'hôte, a billiard room, thirteen private sitting rooms, and six bath rooms.

— John Mayhall, The Annals of Yorkshire, 1878[12]

Plaster cornices and archways decorate the main corridors, with light entering through large lunettes which probably contained coloured glass. There are Greek ornaments over the doors and many marbled pilasters. In each spandrel of the arches which cross the corridors over each bay, is one of Brodrick's characteristic stylised rosettes. The building predominantly houses large numbers of single bedrooms, with double-suites in the corner towers. They were designed as plain and dignified with little decorative plasterwork and austere fireplaces.[6] The original bathhouse had extensive facilities set in the basement under the adjacent terrace; marbled walls and encaustic tiled floors in the stair area are indicators of the original opulence.[8]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wells House, Ilkley. |

- Linstrum 1999, p. 117.

- "Traditional patent glazing – Wells House, Ilkley". Building Design Index. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Linstrum 1978, p. 119.

- Overton Architects (June 2016). Design, Access & Heritage Statement: Wells House (Report). City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council.

- "The origins of Ilkley". Northern Life Magazine. 11 August 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Linstrum 1999, p. 118.

- "On the trail of Darwin in Ilkley". BBC News. 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Ilkley Conservation Area Assessment" (PDF). City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council. March 2002. p. 21. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Sale of college campus is agreed". Telegraph & Argus. 17 October 1998. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Historic England. "Ilkley College Wells House (Grade II) (1133469)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Listed Buildings". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- Mayhall, John (1878). The Annals of Yorkshire (2nd ed.). London. p. 679.

Bibliography

- Linstrum, Derek (1978). West Yorkshire Architects and Architecture. Lund Humphries. ISBN 978-0-85331-410-3.

- Linstrum, Derek (1999). Towers and Colonnades: The Architecture of Cuthbert Brodrick. Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. ISBN 978-1-870737-11-1.