Weight loss

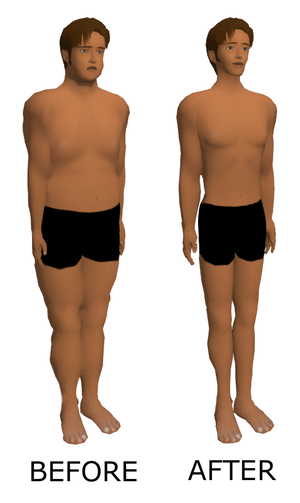

Weight loss, in the context of medicine, health, or physical fitness, refers to a reduction of the total body mass, by a mean loss of fluid, body fat (adipose tissue), or lean mass (namely bone mineral deposits, muscle, tendon, and other connective tissue). Weight loss can either occur unintentionally because of malnourishment or an underlying disease, or from a conscious effort to improve an actual or perceived overweight or obese state. "Unexplained" weight loss that is not caused by reduction in calorific intake or exercise is called cachexia and may be a symptom of a serious medical condition. Intentional weight loss is commonly referred to as slimming.

| Weight loss | |

|---|---|

|

Intentional

Intentional weight loss is the loss of total body mass as a result of efforts to improve fitness and health, or to change appearance through slimming. Weight loss is the main treatment for obesity,[1][2][3] and there is substantial evidence this can prevent progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes with a 7-10% weight loss and manage cardiometabolic health for diabetic people with a 5-15% weight loss.[4]

Weight loss in individuals who are overweight or obese can reduce health risks,[5] increase fitness,[6] and may delay the onset of diabetes.[5] It could reduce pain and increase movement in people with osteoarthritis of the knee.[6] Weight loss can lead to a reduction in hypertension (high blood pressure), however whether this reduces hypertension-related harm is unclear.[5] Weight loss is achieved by adopting a lifestyle in which fewer calories are consumed than are expended.[7] Depression, stress or boredom may contribute to weight increase,[8] and in these cases, individuals are advised to seek medical help. A 2010 study found that dieters who got a full night's sleep lost more than twice as much fat as sleep-deprived dieters.[9][10] Though hypothesized that supplementation of vitamin D may help, studies do not support this.[11] The majority of dieters regain weight over the long term.[12] According to the UK National Health Service and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, those who achieve and manage a healthy weight do so most successfully by being careful to consume just enough calories to meet their needs, and being physically active.[13][7]

In order for weight loss to be permanent, changes in diet and lifestyle must be permanent as well.[14][15][16] There is evidence that counseling or exercise alone do not result in weight loss, whereas dieting alone results in meaningful long-term weight loss, and a combination of dieting and exercise provides the best results.[17] Meal replacements, orlistat and very-low-calorie diet interventions also produce meaningful weight loss.[18]

Techniques

The least intrusive weight loss methods, and those most often recommended, are adjustments to eating patterns and increased physical activity, generally in the form of exercise. The World Health Organization recommends that people combine a reduction of processed foods high in saturated fats, sugar and salt[19] and caloric content of the diet with an increase in physical activity.[20] Self-monitoring of diet, exercise, and weight are beneficial strategies for weight loss,[21][22] particularly early in weight loss programs.[23] Research indicates that those who log their foods about three times per day and about 20 times per month are more likely to achieve clinically significant weight loss.[24]

An increase in fiber intake is recommended for regulating bowel movements. Other methods of weight loss include use of drugs and supplements that decrease appetite, block fat absorption, or reduce stomach volume. Bariatric surgery may be indicated in cases of severe obesity. Two common bariatric surgical procedures are gastric bypass and gastric banding.[25] Both can be effective at limiting the intake of food energy by reducing the size of the stomach, but as with any surgical procedure both come with their own risks[26] that should be considered in consultation with a physician. Dietary supplements, though widely used, are not considered a healthy option for weight loss.[27] Many are available, but very few are effective in the long term.[28]

Virtual gastric band uses hypnosis to make the brain think the stomach is smaller than it really is and hence lower the amount of food ingested. This brings as a consequence weight reduction. This method is complemented with psychological treatment for anxiety management and with hypnopedia. Research has been conducted into the use of hypnosis as a weight management alternative.[29][30][31][32] In 1996, a study found that cognitive-behavioral therapy was more effective for weight reduction if reinforced with hypnosis.[30] Acceptance and commitment therapy, a mindfulness approach to weight loss, has been demonstrated as useful.[33] Herbal medications have also been suggested; however, there is no strong evidence that herbal medicines are effective.[34]

Weight loss industry

There is a substantial market for products which claim to make weight loss easier, quicker, cheaper, more reliable, or less painful. These include books, DVDs, CDs, cremes, lotions, pills, rings and earrings, body wraps, body belts and other materials, fitness centers, clinics, personal coaches, weight loss groups, and food products and supplements.[35]

In 2008, between US$33 billion and $55 billion was spent annually in the US on weight-loss products and services, including medical procedures and pharmaceuticals, with weight-loss centers taking between 6 and 12 percent of total annual expenditure. Over $1.6 billion per year was spent on weight-loss supplements. About 70 percent of Americans' dieting attempts are of a self-help nature.[36][37]

In Western Europe, sales of weight-loss products, excluding prescription medications, topped €1,25 billion (£900 million/$1.4 billion) in 2009.[37]

The scientific soundness of commercial diets by commercial weight management organizations varies widely, being previously non-evidence-based, so there is only limited evidence supporting their use, because of high attrition rates.[38][39][40][41][42][43] Commercial diets result in modest weight loss in the long term, with similar results regardless of the brand,[40][42][44][45] and similarly to non-commercial diets and standard care.[38][3] Comprehensive diet programs, providing counseling and targets for calorie intake, are more efficient than dieting without guidance ("self-help"),[38][46][45] although the evidence is very limited.[43] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence devised a set of essential criteria to be met by commercial weight management organizations to be approved.[41]

Unintentional

Characteristics

Unintentional weight loss may result from loss of body fats, loss of body fluids, muscle atrophy, or a combination of these.[47][48] It is generally regarded as a medical problem when at least 10% of a person's body weight has been lost in six months[47][49] or 5% in the last month.[50] Another criterion used for assessing weight that is too low is the body mass index (BMI).[51] However, even lesser amounts of weight loss can be a cause for serious concern in a frail elderly person.[52]

Unintentional weight loss can occur because of an inadequately nutritious diet relative to a person's energy needs (generally called malnutrition). Disease processes, changes in metabolism, hormonal changes, medications or other treatments, disease- or treatment-related dietary changes, or reduced appetite associated with a disease or treatment can also cause unintentional weight loss.[47][48][53][54][55] Poor nutrient utilization can lead to weight loss, and can be caused by fistulae in the gastrointestinal tract, diarrhea, drug-nutrient interaction, enzyme depletion and muscle atrophy.[49]

Continuing weight loss may deteriorate into wasting, a vaguely defined condition called cachexia.[52] Cachexia differs from starvation in part because it involves a systemic inflammatory response.[52] It is associated with poorer outcomes.[47][52][53] In the advanced stages of progressive disease, metabolism can change so that they lose weight even when they are getting what is normally regarded as adequate nutrition and the body cannot compensate. This leads to a condition called anorexia cachexia syndrome (ACS) and additional nutrition or supplementation is unlikely to help.[49] Symptoms of weight loss from ACS include severe weight loss from muscle rather than body fat, loss of appetite and feeling full after eating small amounts, nausea, anemia, weakness and fatigue.[49]

Serious weight loss may reduce quality of life, impair treatment effectiveness or recovery, worsen disease processes and be a risk factor for high mortality rates.[47][52] Malnutrition can affect every function of the human body, from the cells to the most complex body functions, including:[51]

- immune response;

- wound healing;

- muscle strength (including respiratory muscles);

- renal capacity and depletion leading to water and electrolyte disturbances;

- thermoregulation; and

- menstruation.

Malnutrition can lead to vitamin and other deficiencies and to inactivity, which in turn may pre-dispose to other problems, such as pressure sores.[51] Unintentional weight loss can be the characteristic leading to diagnosis of diseases such as cancer[47] and type 1 diabetes.[56] In the UK, up to 5% of the general population is underweight, but more than 10% of those with lung or gastrointestinal diseases and who have recently had surgery.[51] According to data in the UK using the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool ('MUST'), which incorporates unintentional weight loss, more than 10% of the population over the age of 65 is at risk of malnutrition.[51] A high proportion (10–60%) of hospital patients are also at risk, along with a similar proportion in care homes.[51]

Causes

Disease-related

Disease-related malnutrition can be considered in four categories:[51]

| Problem | Cause |

|---|---|

| Impaired intake | Poor appetite can be a direct symptom of an illness, or an illness could make eating painful or induce nausea. Illness can also cause food aversion.

Inability to eat can result from: diminished consciousness or confusion, or physical problems affecting the arm or hands, swallowing or chewing. Eating restrictions may also be imposed as part of treatment or investigations. Lack of food can result from: poverty, difficulty in shopping or cooking, and poor quality meals. |

| Impaired digestion &/or absorption | This can result from conditions that affect the digestive system. |

| Altered requirements | Changes to metabolic demands can be caused by illness, surgery and organ dysfunction. |

| Excess nutrient losses | Losses from the gastrointestinal can occur because of symptoms such as vomiting or diarrhea, as well as fistulae and stomas. There can also be losses from drains, including nasogastric tubes.

Other losses: Conditions such as burns can be associated with losses such as skin exudates. |

Weight loss issues related to specific diseases include:

- As chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) advances, about 35% of patients experience severe weight loss called pulmonary cachexia, including diminished muscle mass.[53] Around 25% experience moderate to severe weight loss, and most others have some weight loss.[53] Greater weight loss is associated with poorer prognosis.[53] Theories about contributing factors include appetite loss related to reduced activity, additional energy required for breathing, and the difficulty of eating with dyspnea (labored breathing).[53]

- Cancer, a very common and sometimes fatal cause of unexplained (idiopathic) weight loss. About one-third of unintentional weight loss cases are secondary to malignancy. Cancers to suspect in patients with unexplained weight loss include gastrointestinal, prostate, hepatobiliary (hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer), ovarian, hematologic or lung malignancies.

- People with HIV often experience weight loss, and it is associated with poorer outcomes.[57] Wasting syndrome is an AIDS-defining condition.[57]

- Gastrointestinal disorders are another common cause of unexplained weight loss – in fact they are the most common non-cancerous cause of idiopathic weight loss. Possible gastrointestinal etiologies of unexplained weight loss include: celiac disease, peptic ulcer disease, inflammatory bowel disease (crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis), pancreatitis, gastritis, diarrhea and many other GI conditions.

- Infection. Some infectious diseases can cause weight loss. Fungal illnesses, endocarditis, many parasitic diseases, AIDS, and some other subacute or occult infections may cause weight loss.

- Renal disease. Patients who have uremia often have poor or absent appetite, vomiting and nausea. This can cause weight loss.

- Cardiac disease. Cardiovascular disease, especially congestive heart failure, may cause unexplained weight loss.

- Connective tissue disease

- Oral, taste or dental problems (including infections) can reduce nutrient intake leading to weight loss.[49]

Therapy-related

Medical treatment can directly or indirectly cause weight loss, impairing treatment effectiveness and recovery that can lead to further weight loss in a vicious cycle.[47] Many patients will be in pain and have a loss of appetite after surgery.[47] Part of the body's response to surgery is to direct energy to wound healing, which increases the body's overall energy requirements.[47] Surgery affects nutritional status indirectly, particularly during the recovery period, as it can interfere with wound healing and other aspects of recovery.[47][51] Surgery directly affects nutritional status if a procedure permanently alters the digestive system.[47] Enteral nutrition (tube feeding) is often needed.[47] However a policy of 'nil by mouth' for all gastrointestinal surgery has not been shown to benefit, with some weak evidence suggesting it might hinder recovery.[58] Early post-operative nutrition is a part of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocols.[59] These protocols also include carbohydrate loading in the 24 hours before surgery, but earlier nutritional interventions have not been shown to have a significant impact.[59]

Social conditions

Social conditions such as poverty, social isolation and inability to get or prepare preferred foods can cause unintentional weight loss, and this may be particularly common in older people.[60] Nutrient intake can also be affected by culture, family and belief systems.[49] Ill-fitting dentures and other dental or oral health problems can also affect adequacy of nutrition.[49]

Loss of hope, status or social contact and spiritual distress can cause depression, which may be associated with reduced nutrition, as can fatigue.[49]

Myths

Some popular beliefs attached to weight loss have been shown to either have less effect on weight loss than commonly believed or are actively unhealthy. According to Harvard Health, the idea of metabolism being the "key to weight" is "part truth and part myth" as while metabolism does affect weight loss, external forces such as diet and exercise have an equal effect.[61] They also commented that the idea of changing one's rate of metabolism is under debate.[61] Diet plans in fitness magazines are also often believed to be effective but may actually be harmful by limiting the daily intake of important calories and nutrients which can be detrimental depending on the person and are even capable of driving individuals away from weight loss.[62]

Health effects

Obesity increases health risks, including diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, to name a few. Reduction of obesity lowers those risks. A 1-kg loss of body weight has been associated with an approximate 1-mm Hg drop in blood pressure.[63] Intentional weight loss is associated with cognitive performance improvements in overweight and obese individuals.[64]

See also

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). "2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans - health.gov". health.gov. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Arnett, Donna K.; Blumenthal, Roger S.; Albert, Michelle A.; Buroker, Andrew B.; Goldberger, Zachary D.; Hahn, Ellen J.; Himmelfarb, Cheryl D.; Khera, Amit; Lloyd-Jones, Donald; McEvoy, J. William; Michos, Erin D.; Miedema, Michael D.; Muñoz, Daniel; Smith, Sidney C.; Virani, Salim S.; Williams, Kim A.; Yeboah, Joseph; Ziaeian, Boback (17 March 2019). "2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease". Circulation. 140 (11): e596–e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678. PMID 30879355.

- Jensen, MD; Ryan, DH; Apovian, CM; Ard, JD; Comuzzie, AG; Donato, KA; Hu, FB; Hubbard, VS; Jakicic, JM; Kushner, RF; Loria, CM; Millen, BE; Nonas, CA; Pi-Sunyer, FX; Stevens, J; Stevens, VJ; Wadden, TA; Wolfe, BM; Yanovski, SZ; Jordan, HS; Kendall, KA; Lux, LJ; Mentor-Marcel, R; Morgan, LC; Trisolini, MG; Wnek, J; Anderson, JL; Halperin, JL; Albert, NM; Bozkurt, B; Brindis, RG; Curtis, LH; DeMets, D; Hochman, JS; Kovacs, RJ; Ohman, EM; Pressler, SJ; Sellke, FW; Shen, WK; Smith SC, Jr; Tomaselli, GF; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice, Guidelines.; Obesity, Society. (24 June 2014). "2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society". Circulation (Professional society guideline). 129 (25 Suppl 2): S102-38. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. PMC 5819889. PMID 24222017.

- Evert, Alison B.; Dennison, Michelle; Gardner, Christopher D.; Garvey, W. Timothy; Lau, Ka Hei Karen; MacLeod, Janice; Mitri, Joanna; Pereira, Raquel F.; Rawlings, Kelly; Robinson, Shamera; Saslow, Laura; Uelmen, Sacha; Urbanski, Patricia B.; Yancy, William S. (May 2019). "Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report". Diabetes Care (Professional society guidelines). 42 (5): 731–754. doi:10.2337/dci19-0014. PMC 7011201. PMID 31000505.

- LeBlanc, E; O'Connor, E; Whitlock, EP (October 2011). "Screening for and management of obesity and overweight in adults". Evidence Syntheses, No. 89. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. "Health benefits of losing weight". Fact sheet, Informed Health Online. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- "Health Weight – Understanding Calories". National Health Service. 19 August 2016.

- "Moods for Overeating: Good, Bad, and Bored". Psychology Today. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- Nedeltcheva, AV; Kilkus, JM; Imperial, J; Schoeller, DA; Penev, PD (2010). "Insufficient sleep undermines dietary efforts to reduce adiposity". Annals of Internal Medicine. 153 (7): 435–41. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-153-7-201010050-00006. PMC 2951287. PMID 20921542.

- Harmon, Katherine (4 October 2010). "Sleep might help dieters shed more fat". Scientific American. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- Pathak, K.; Soares, M. J.; Calton, E. K.; Zhao, Y.; Hallett, J. (1 June 2014). "Vitamin D supplementation and body weight status: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Obesity Reviews. 15 (6): 528–37. doi:10.1111/obr.12162. ISSN 1467-789X. PMID 24528624.

- Sumithran, Priya; Proietto, Joseph (2013). "The defence of body weight: A physiological basis for weight regain after weight loss". Clinical Science. 124 (4): 231–41. doi:10.1042/CS20120223. PMID 23126426.

- "Executive Summary". Dietary Guidelines 2015–2020. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Hart, Katherine (2018). "4.6 Fad diets and fasting for weight loss in obesity.". In Hankey, Catherine (ed.). Advanced nutrition and dietetics in obesity. Wiley. pp. 177–182. ISBN 9780470670767.

- Hankey, Catherine (23 November 2017). Advanced Nutrition and Dietetics in Obesity. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 179–181. ISBN 9781118857977.

- "Fact Sheet—Fad diets" (PDF). British Dietetic Association. 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

Fad-diets can be tempting as they offer a quick-fix to a long-term problem.

- The Look AHEAD Research Group (2014). "Eight-year weight losses with an intensive lifestyle intervention: The look AHEAD study: 8-Year Weight Losses in Look AHEAD". Obesity. 22 (1): 5–13. doi:10.1002/oby.20662. PMC 3904491. PMID 24307184.

- Thom, G; Lean, M (May 2017). "Is There an Optimal Diet for Weight Management and Metabolic Health?" (PDF). Gastroenterology. 152 (7): 1739–1751. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.056. PMID 28214525.

- "World Health Organization recommends eating less processed food". BBC News. 3 March 2003.

- "Choosing a safe and successful weight loss program". Weight-control Information Network. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Burke, Lora E.; Wang, Jing; Sevick, Mary Ann (2011). "Self-Monitoring in Weight Loss: A Systematic Review of the Literature". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 111 (1): 92–102. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.008. PMC 3268700. PMID 21185970.

- Steinberg, Dori M.; Tate, Deborah F.; Bennett, Gary G.; Ennett, Susan; Samuel-Hodge, Carmen; Ward, Dianne S. (2013). "The efficacy of a daily self-weighing weight loss intervention using smart scales and e-mail: Daily Self-Weighing Weight Loss Intervention". Obesity. 21 (9): 1789–97. doi:10.1002/oby.20396. PMC 3788086. PMID 23512320.

- Krukowski, Rebecca A.; Harvey-Berino, Jean; Bursac, Zoran; Ashikaga, Taka; West, Delia Smith (2013). "Patterns of success: Online self-monitoring in a web-based behavioral weight control program". Health Psychology. 32 (2): 164–170. doi:10.1037/a0028135. ISSN 1930-7810. PMC 4993110. PMID 22545978.

- Harvey, Jean; Krukowski, Rebecca; Priest, Jeff; West, Delia (2019). "Log Often, Lose More: Electronic Dietary Self-Monitoring for Weight Loss: Log Often, Lose More". Obesity. 27 (3): 380–384. doi:10.1002/oby.22382. PMC 6647027. PMID 30801989.

- Albgomi. "Bariatric Surgery Highlights and Facts". Bariatric Surgery Information Guide. bariatricguide.org. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- "Gastric bypass risks". Mayo Clinic. 9 February 2009.

- Neumark-Sztainer, Dianne; Sherwood, Nancy E.; French, Simone A.; Jeffery, Robert W. (March 1999). "Weight control behaviors among adult men and women: Cause for concern?". Obesity Research. 7 (2): 179–88. doi:10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00700.x. PMID 10102255.

- Thomas, Paul R. (January–February 2005). "Dietary Supplements For Weight Loss?". Nutrition Today. 40 (1): 6–12.

- Barabasz, Marianne; Spiegel, David (1989). "Hypnotizability and weight loss in obese subjects". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 8 (3): 335–41. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198905)8:3<335::AID-EAT2260080309>3.0.CO;2-O.

- Kirsch, I. (June 1996). "Hypnotic enhancement of cognitive-behavioral weight loss treatments–another meta-reanalysis". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 64 (3): 517–19. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.64.3.517. PMID 8698945. INIST:3143031.

- Andersen, M. S. (1985). "Hypnotizability as a factor in the hypnotic treatment of obesity". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 33 (2): 150–59. doi:10.1080/00207148508406645. PMID 4018924.

- Allison, David B.; Faith, Myles S. (June 1996). "Hypnosis as an adjunct to cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for obesity: A meta-analytic reappraisal". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 64 (3): 513–16. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.64.3.513. PMID 8698944.

- Ruiz, F. J. (2010). "A review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) empirical evidence: Correlational, experimental psychopathology, component and outcome studies". International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 10 (1): 125–62.

- Maunder, Alison; Bessell, Erica; Lauche, Romy; Adams, Jon; Sainsbury, Amanda; Fuller, Nicholas R. (27 January 2020). "Effectiveness of herbal medicines for weight loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 22 (6): 891–903. doi:10.1111/dom.13973. ISSN 1463-1326. PMID 31984610.

- "The facts about weight loss products and programs". DHHS Publication No (FDA) 92-1189. US Food and Drug Administration. 1992. Archived from the original on 26 September 2006. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- "Profiting From America's Portly Population". PRNewswire (Press release). Reuters. 21 April 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- "No evidence that popular slimming supplements facilitate weight loss, new research finds". 14 July 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- Thom, G; Lean, M (May 2017). "Is There an Optimal Diet for Weight Management and Metabolic Health?" (PDF). Gastroenterology (Review). 152 (7): 1739–1751. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.056. PMID 28214525.

- Wadden, Thomas A.; Webb, Victoria L.; Moran, Caroline H.; Bailer, Brooke A. (6 March 2012). "Lifestyle Modification for Obesity". Circulation (Narrative review). 125 (9): 1157–1170. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039453. PMC 3313649. PMID 22392863.

- Atallah, R.; Filion, K. B.; Wakil, S. M.; Genest, J.; Joseph, L.; Poirier, P.; Rinfret, S.; Schiffrin, E. L.; Eisenberg, M. J. (11 November 2014). "Long-Term Effects of 4 Popular Diets on Weight Loss and Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials". Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes (Systematic review of RCTs). 7 (6): 815–827. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000723. PMID 25387778.

- Avery, Amanda (2018). "4.7 Commercial weight management organisations for weight loss in obesity.". In Hankey, Catherine (ed.). Advanced nutrition and dietetics in obesity. Wiley. pp. 177–182. ISBN 9780470670767.

- Tsai, AG; Wadden, TA (4 January 2005). "Systematic review: an evaluation of major commercial weight loss programs in the United States". Annals of Internal Medicine (Systematic review). 142 (1): 56–66. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-1-200501040-00012. PMID 15630109.

- Allan, Karen (2018). "4.4 Group‐based interventions for weight loss in obesity.". In Hankey, Catherine (ed.). Advanced nutrition and dietetics in obesity. Wiley. pp. 164–168. ISBN 9780470670767.

- Vakil, RM; Doshi, RS; Mehta, AK; Chaudhry, ZW; Jacobs, DK; Lee, CJ; Bleich, SN; Clark, JM; Gudzune, KA (1 June 2016). "Direct comparisons of commercial weight-loss programs on weight, waist circumference, and blood pressure: a systematic review". BMC Public Health (Systematic review). 16: 460. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3112-z. PMC 4888663. PMID 27246464.

- Gudzune, KA; Doshi, RS; Mehta, AK; Chaudhry, ZW; Jacobs, DK; Vakil, RM; Lee, CJ; Bleich, SN; Clark, JM (7 April 2015). "Efficacy of commercial weight-loss programs: an updated systematic review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (7): 501–512. doi:10.7326/M14-2238. PMC 4446719. PMID 25844997.

- Kernan, Walter N.; Inzucchi, Silvio E.; Sawan, Carla; Macko, Richard F.; Furie, Karen L. (January 2013). "Obesity - A Stubbornly Obvious Target for Stroke Prevention". Stroke (Review). 44 (1): 278–286. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.639922. PMID 23111440.

- National Cancer Institute (November 2011). "Nutrition in cancer care (PDQ)". Physician Data Query. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- Huffman, GB (15 February 2002). "Evaluating and treating unintentional weight loss in the elderly". American Family Physician. 65 (4): 640–50. PMID 11871682.

- Payne, C; Wiffen, PJ; Martin, S (18 January 2012). Payne, Cathy (ed.). "Interventions for fatigue and weight loss in adults with advanced progressive illness". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD008427. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008427.pub2. PMID 22258985. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008427.pub3. If this is an intentional citation to a retracted paper, please replace

{{Retracted}}with{{Retracted|intentional=yes}}.) - Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Nutrition Services for Medicare Beneficiaries (9 June 2000). The role of nutrition in maintaining health in the nation's elderly: evaluating coverage of nutrition services for the Medicare population. National Academies Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-309-06846-8.

- National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care (UK) (February 2006). "Nutrition Support for Adults: Oral Nutrition Support, Enteral Tube Feeding and Parenteral Nutrition". NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 32. National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care (UK).

- Yaxley, A; Miller, MD; Fraser, RJ; Cobiac, L (February 2012). "Pharmacological interventions for geriatric cachexia: a narrative review of the literature". The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 16 (2): 148–54. doi:10.1007/s12603-011-0083-8. PMID 22323350.

- Itoh, M; Tsuji, T; Nemoto, K; Nakamura, H; Aoshiba, K (18 April 2013). "Undernutrition in patients with COPD and its treatment". Nutrients. 5 (4): 1316–35. doi:10.3390/nu5041316. PMC 3705350. PMID 23598440.

- Mangili A, Murman DH, Zampini AM, Wanke CA; Murman; Zampini; Wanke (2006). "Nutrition and HIV infection: review of weight loss and wasting in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy from the nutrition for healthy living cohort". Clin. Infect. Dis. 42 (6): 836–42. doi:10.1086/500398. PMID 16477562.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Nygaard, B (19 July 2010). "Hyperthyroidism (primary)". Clinical Evidence. 2010: 0611. PMC 3275323. PMID 21418670.

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions (UK) (2004). Type 1 diabetes in adults: National clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 15.1. Royal College of Physicians UK. ISBN 978-1860162282. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- Mangili, A; Murman, DH; Zampini, AM; Wanke, CA (15 March 2006). "Nutrition and HIV infection: review of weight loss and wasting in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy from the nutrition for healthy living cohort". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 42 (6): 836–42. doi:10.1086/500398. PMID 16477562.

- Herbert, Georgia; Perry, Rachel; Andersen, Henning Keinke; Atkinson, Charlotte; Penfold, Christopher; Lewis, Stephen J.; Ness, Andrew R.; Thomas, Steven (2018). "Early enteral nutrition within 24 hours of lower gastrointestinal surgery versus later commencement for length of hospital stay and postoperative complications". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD004080. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004080.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6517065. PMID 30353940.

- Burden, S; Todd, C; Hill, J; Lal, S (2012). Burden, Sorrel (ed.). "Pre‐operative Nutrition Support in Patients Undergoing Gastrointestinal Surgery" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (11): CD008879. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008879.pub2. PMID 23152265. Lay summary.

- Alibhai, SM; Greenwood, C; Payette, H (15 March 2005). "An approach to the management of unintentional weight loss in elderly people". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 172 (6): 773–80. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1031527. PMC 552892. PMID 15767612.

- "Does Metabolism Matter in Weight Loss?". Harvard Health. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- Long, Jacqueline (2015). The Gale Encyclopedia of Senior Health. Detroit, MI: Gale. ISBN 978-1573027526.

- Harsha, D. W.; Bray, G. A. (2008). "Weight Loss and Blood Pressure Control (Pro)". Hypertension. 51 (6): 1420–25. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.547.1622. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.094011. ISSN 0194-911X. PMID 18474829.

- Veronese, N; Facchini, S; Stubbs, B; Luchini, C; Solmi, M; Manzato, E; Sergi, G; Maggi, S; Cosco, T; Fontana, L (January 2017). "Weight loss is associated with improvements in cognitive function among overweight and obese people: A systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 72: 87–94. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.11.017. PMID 27890688.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Lentis/The Weight Loss Industry in the United States |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Fundamentals of Human Nutrition/Weight management |

| Classification |

|---|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Weight loss. |

- Weight loss at Curlie

- Health benefits of losing weight By IQWiG at PubMed Health

- Weight-control Information Network U.S. National Institutes of Health

- Nutrition in cancer care By NCI at PubMed Health

- Unintentional weight loss