Water in Africa

Overall, Africa has about 9% of the world's fresh water resources and 16% of the world's population.[1][2] However, there is very significant inter-and intra-annual variability of all climate and water resources characteristics, so while some regions have sufficient water,[2] Sub-Saharan Africa faces numerous water-related challenges that constrain economic growth and threaten the livelihoods of its people.[2] African agriculture is mostly based on rain-fed farming, and less than 10% of cultivated land in the continent is irrigated.[1][2] The impact of climate change and variability is thus very pronounced.[2] The main source of electricity is hydropower, which contributes significantly to the current installed capacity for energy.[2] Continuing investment in the last decade has increased the amount of power generated.[2]

Solutions to the challenges of water for energy and food security are hindered by shortcomings in water infrastructure, development, and management capacity to meet the demands of a rapidly growing population.[2] This is compounded by the fact the Africa has the fastest urbanization rates in the world.[2][3] Water development and management are much more complex due to the multiplicity of trans-boundary water resources (rivers, lakes and aquifers).[2] Around 75% of sub-Saharan Africa falls within 53 international river basin catchments that traverse multiple borders.[1][2] This particular constraint can also be converted into an opportunity if the potential for trans-boundary cooperation is harnessed in the development of the area’s water resources.[2] A multi-sectoral analysis of the Zambezi River, for example, shows that riparian cooperation could lead to a 23% increase in firm energy production without any additional investments.[1][2] A number of institutional and legal frameworks for transboundary cooperation exist, such as the Zambezi River Authority, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Protocol, Volta River Authority and the Nile Basin Commission.[2] However, additional efforts are required to further develop political will, as well as the financial capacities and institutional frameworks needed for win-win multilateral cooperative actions and optimal solutions for all riparians.[2]

Water, jobs and the economy

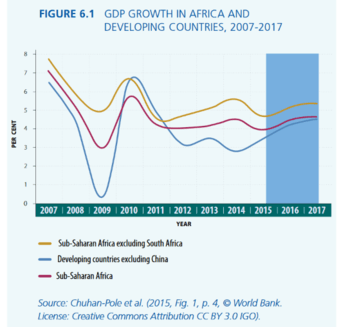

Africa has recently undergone its best decade (2005-2015) for economic growth since the post-independence period. The growth, however, has neither been inclusive or equitable.[2] According to the World Bank, GDP growth in sub-Saharan Africa averaged 4.5% in 2014, up from 4.2% in 2013, supported by continuing infrastructure investment, increased agricultural production and buoyant services.[2]

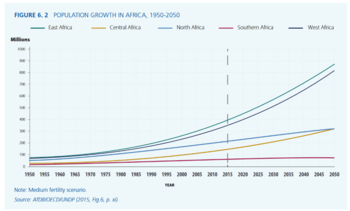

Africa’s population surpassed the 1 billion mark in 2010 and is projected to double by 2050.[2][4] Demographically, it is expected to be the fastest growing region in the world with the growth varying depending on sub region.[2] Furthermore, the growth is skewed to the young and that component of the population that will need jobs is expected to increase rapidly and comprise 910 million out of the projected two billion total population by 2050.[2] Most of the growth in workforce will be in Sub-Saharan Africa (about 90%).[2] Hence, the demand for jobs will be a major policy issue across the continent, which is already experiencing high unemployment and underemployment; moreover, the latter is driving both migration within the region and emigration towards Europe and other regions.[2]

Job creation for this anticipated growth in population is set to be the major challenge for Africa’s structural economic and social transformation.[2] It is estimated that in 2015, 19 million young people will be joining the sluggish job market in Sub-Saharan Africa and four million in North Africa.[2] The demand for jobs is expected to increase to 24.6 million annually in Sub-Saharan Africa and 4.3 million in North Africa by 2030, representing two thirds of global growth in demand for jobs.[2][4] Youth unemployment has been the trigger for uprisings, notably in North Africa, and has led to social and security instability.[2]

The key water-dependent or related sectors with the potential for meeting part of the current and projected demand for jobs in Africa are social services, agriculture, fisheries and aquaculture, retail and hospitality, manufacturing, construction, natural resources exploitation (including mining) and energy production (including hydro, geothermal and expected fracking for oil and natural gas).[2] All these sectors depend to a varying extent on the availability of, access to, and reliability of water resources.[2] Irresponsible water use by some sectors can create short-term employment, but result in negative impacts on the availability of water resources and jeopardize future jobs in other water-dependent sectors.[2] Climate change, water scarcity and variability have direct impact on the major sector outputs and thus ultimately on the overall economy of most African countries.[2]

Jobs in water-dependent sectors

Currently, the most important water-dependent sector in Africa is agriculture, which forms the bedrock of most economies of African states.[2] Both rain-fed and irrigated agriculture are important job-providing sectors in all African countries.[2]

Agriculture

The role of agriculture as the main source of employment is decreasing in many African countries as a sustained growth in many economies is leading to increasing standards of living, improved education and the occurrence of rapid rural-urban migration of educated youth in search of white collar jobs.[2] However, for the foreseeable future agriculture will still be a major source of employment, especially in non-oil producing African states.[2] There is a rising paradox of increasing unemployment in the rapidly urbanizing cities and towns of Africa: labour shortages in rural areas are leading to significant reduction in food production and increased dependence of many African countries on food imports.[2]

Based on Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations statistics, agriculture was the source of employment for 49% of Africans by 2010 and is a reflection of a gradual decline from 2002 to 2010,which coincides with the period of sustained GDP growth in most African countries.[2][5] In spite of this decline, agriculture is expected to create eight million stable jobs by 2020 based on the trends from the McKinsey Global Institute analysis.[2] If the continent accelerates agricultural development by expanding large scale commercial farming on uncultivated land and shifts production from low-value grain production to more labour-intensive and higher value-added horticultural and bio fuel crops (a good example is Ethiopia), as many as six million additional jobs could be created continent-wide by 2020.[2][6] However, such estimates do not take account of the potential displacement or disappearance of existing jobs.[2] These would need to be carefully assessed in terms of social, economic and environmental impacts in the overall context of responsible agricultural investment.[2]

Fisheries

The African fisheries and aquaculture sector employed12.3 million people in 2014 and contributed US $24 billion or 1.26% of the GDP of all African countries, which improved food security and nutrition.[2] About half of the workers in the sector were fishers and the rest were processors (mainly women) or aquaculturists.[2][7]

Fisheries and aquaculture contribution to GDP in Africa by sub-sector

| [2] | Gross value added

(US$ millions) |

Contribution

to GDP (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total GDPs African countries | 1,909,514 | |

| Total fisheries and aquaculture | 24,030 | 1.26 |

| Total inland fisheries | 4,676 | 0.24 |

| Post-harvest | 1,590 | 0.08 |

| Local licenses | 8 | 0 |

| Total marine artisanal fisheries | 8,130 | 0.43 |

| Marine artisanal fisheries | 5,246 | 0.27 |

| Post-harvest | 2,870 | 0.15 |

| Local licenses | 13 | 0 |

| Total marine industrial fisheries | 6,849 | 0.36 |

| Marine industrial fishing | 4,670 | 0.24 |

| Post-harvest | 1,878 | 0.10 |

| Local licenses | 302 | 0.02 |

| Total aquaculture | 2,776 | 0.15 |

Employment by subsector

| [2] | Number of employees (thousands) | Share subsector (%) | Share with sector (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total employment | 12,269 | ||

| Total Inland fisheries | 4,958 | 40.4 | |

| Fishers | 3,370 | 68.0 | |

| Producers | 1,588 | 32.0 | |

| Total Marine Artisanal Fisheries | 4,041 | 32.9 | |

| Fishers | 1,876 | 46.4 | |

| Producers | 2,166 | 53.6 | |

| Total Marine Industrial Fisheries | 2,350 | 19.2 | |

| Fishers | 901 | 38.4 | |

| Producers | 61.6 | ||

| Aquaculture workers | 920 | 7.5 |

Manufacturing and industry

Many manufacturing industries in Africa are water-dependent.[2] The share of jobs is lower than in agriculture, even though the industries cited are considered as water intensive.[2] In 2011, Ghana’s economy grew at 14% with the onset of its first production of oil.[2][8] However, in 2015 the growth rate was expected to be only 3.9%.[2][9] This can be attributed to a great extent to the failure to provide the basic water and energy infrastructure to meet the needs of a rapidly growing economy.[2] Ghana is mainly dependent on the Akosombo hydroelectric dam on the Volta River for electricity.[2] Due to reduced inflows from low rainfall, the hydroelectric dam was operating merely at half of its capacity in 2015.[2][10] This was exacerbated by disruptions mainly in geothermal plants.[2] In June 2015, all electricity was being rationed at 12 hours on, and 24 hours off.[2] Though this is extreme, it reinforces the need for water infrastructure to sustain production and jobs in the nascent African economies.[2] Anecdotal evidence from trade unions and employers in Ghana indicate that tens of thousands of stable jobs were lost in 2015 and the investment climate has turned sour, forcing Ghana to seek International Monetary Fund macro-economic support again.[2][11] These policy instruments are underpinned by strategies and programmes, including the New Partnership for African Development Program (NEPAD), Program for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) and many others, which include the integrated development of Africa’s water resources for socio-economic development and poverty alleviation and eradication.[2] The AU Agenda 2063, for example, aspires to a prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development.[2] It specifically aims for an Africa that shall have equitable and sustainable use and management of water resources for socio-economic development, regional cooperation and the environment, and calls for the following action among others.[2] ‘Support Young people as drivers of Africa’s renaissance, through investment in their health,education and access to technology, opportunities and capital, and concerted strategies to combat youth unemployment and underemployment.[2] Encourage exchange and Pan-Africanism among young people through the formation of African Union Clubs in all schools, colleges and universities.[2] Ensure faster movement on the harmonization of continental admissions, curricula, standards, programmes and qualifications and raising the standards of higher education to enhance the mobility of African youth and talent across the continent by 2025’.[11]

Expected future developments

For Africa to be able to meet the Sustainable Development Goals and maintain the impressive growth rates of the last 10 years, the basic infrastructures of water, electricity and transportation are prerequisites.[2] Without these basics, the African economies will lose the momentum of the last decade, which will lead to not only loss of direct water jobs, but also jobs in all the other sectors dependent on water.[2] An illustrative example is the case of Ghana which is often cited as one of the best examples of economic recovery in Africa.[2]

African Water Policy Framework and impact on jobs

The African Policy Framework for the water sector comprise a series of high-level declarations,resolutions and programmes of action on the development and use of the continent’s water resources for socio-economic development, regional integration and the environment.[2] These include the African Water Vision 2025 and its Framework of Action, the African Union (AU) Extraordinary Summit on Water and Agriculture, the AU Sharm El Sheikh Declaration on Water and Sanitation, and most importantly, the Agenda 2063 –The Africa We Want.[12][12][13]

These policy instruments are underpinned by strategies and programmes, including the New Partnership for African Development Program (NEPAD), Program for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) and many others, which include the integrated development of Africa’s water resources for socio-economic development and poverty alleviation and eradication.[2]

The AU Agenda 2063, for example, aspires to a prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development.[2] It specifically aims for an Africa that shall have equitable and sustainable use and management of water resources for socio-economic development, regional cooperation and the environment, and calls for the following action among others.[2] ‘Support Young people as drivers of Africa’s renaissance, through investment in their health,education and access to technology, opportunities and capital, and concerted strategies to combat youth unemployment and underemployment.[2] Encourage exchange and Pan-Africanism among young people through the formation of African Union Clubs in all schools, colleges and universities.[2] Ensure faster movement on the harmonization of continental admissions, curricula, standards, programmes and qualifications and raising the standards of higher education to enhance the mobility of African youth and talent across the continent by 2025’.[2][12]

Sources

![]()

References

- "Cooperation in International Waters in Africa (CIWA)". www.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- The United Nations World Water Development Report 2016: Water and Jobs. Paris: UNESCO. 2016. ISBN 978-92-3-100146-8.

- Rafei, Leila (2014-10-29). "Africa's urban population growth: trends and projections". The Data Blog. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- AfDB; UNDP; OECD (2015). African Economic Outlook, Books / African Economic Outlook / 2015:Regional Development and Spatial Inclusion. African Economic Outlook. doi:10.1787/aeo-2015-en. ISBN 9789264232822.

- The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Opportunities and Challenges. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3720e.pdf: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2014. ISBN 978-92-5-108276-8.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Africa at work: Job creation and inclusive growth". McKinsey & Company. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- The Value of African Fisheries. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3917e.pdf: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2014.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Ghana's Economic Performance 2011. Ghana Statistical Service. 2012.

- "Ghana | African Economic Outlook". African Economic Outlook. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- Ofori-Atta, Prince. "Electricity: Ghana's power crisis deepens | West Africa". www.theafricareport.com. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- Sirte Declaration on the Challenges of Implementing Integrated and Sustainable Development on Agriculture and Water in Africa. http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/sirte2008/Declaration-Sirte%202004.pdf: African Union. 2004.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Sirte Declaration On The Challenges Of Implementing Integrated And Sustainable Development In Agriculture And Water In Africa. African Union. 2004.

- The Africa Water Vision for 2025: Equitable and Sustainable Use of Water for Socioeconomic Development. http://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Generic-Documents/african%20water%20vision%202025%20to%20be%20sent%20to%20wwf5.pdf: African Development Bank Group.CS1 maint: location (link)