Wappinger

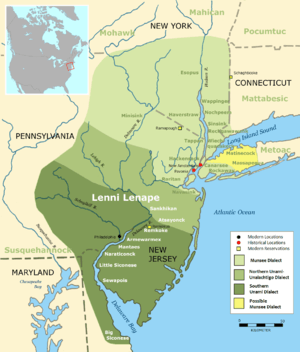

The Wappinger (/ˈwɒpɪndʒər/)[2] were an Eastern Algonquian-speaking tribe from New York and Connecticut. They lived on the east bank of the Hudson River eastward to the Connecticut River valley.[1]

.jpg) Wappinger territory (in center, "Wappinges"), from a 1685 reprint of a 1656 map | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (Extinct as a tribe)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Eastern Algonquian languages, probably Munsee[1] | |

| Religion | |

| traditional tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Algonquian peoples |

In the 17th century, they were primarily based in what is now Dutchess County, New York, and their territory included the east bank of the Hudson in what became both Putnam and Westchester counties south to Manhattan Island.[3] To the north, the Roeliff-Jansen Kill marked the beginning of Mahican territory.[4] The totem (or emblem) of the Wappinger was the “enchanted wolf”, with the right paw raised defiantly. They shared this totem with the Mahicans – their closest allies, located to the north.[5]

Name

The origin of the name Wappinger is unknown. While the present-day spelling was used as early as 1643,[6] countless alternate phonetic spellings were also used by early European settlers well into the late 19th century. Each linguistic group tended to transliterate Native American names according to their own languages. Among these spellings and terms are:

- Wappink, Wappings, Wappingers, Wappingoes, Wawpings, Pomptons, Wapings, Opings, Opines,[7] Massaco,[8] Menunkatuck,[9] Naugatuck,[10] Nochpeem,[11] Wangunk[1] Wappans, Wappings, Wappinghs,[12] Wapanoos, Wappanoos, Wappinoo, Wappenos, Wappinoes, Wappinex, Wappinx, Wapingeis, Wabinga, Wabingies, Wapingoes, Wapings, Wappinges, Wapinger and Wappenger.[6]

Anthropologist Ives Goddard suggests the Munsee language-word wápinkw, used by the Lenape and meaning "opossum", might be related to the name Wappinger.[13][14] No evidence supports the folk etymology of the name coming from a word meaning "easterner," as suggested by Edward Manning Ruttenber in 1906[4] and John Reed Swanton in 1952.[15]

Others suggest that Wappinger is anglicized from the Dutch word wapendragers, meaning "weapon-bearers", alluding to the warring relationship between the Dutch and the Wappinger.[4][16] Such reference would correspond to a first appearance in 1643. This was thirty-four years after the Dutch aboard Hudson's Half Moon may have learned the name the people called themselves. The 1643 date reflects a period of great conflict with the natives, including the preemptive Pavonia massacre by the Dutch, which precipitated Keift's War.

Language

The Wappinger were most closely related to the Lenape,[lower-alpha 1] as both were among the Eastern Algonquian-speaking subgroup of the Algonquian peoples. The Lenape and Wappinger spoke using very similar Delawarean languages.

Their nearest allies were the Mahican to the north, the Montaukett to the southeast on Long Island, and the remaining New England tribes to the east. Like the Lenape, the Wappinger were highly decentralized as a people. They formed approximately 18 loosely associated bands that had established geographic territories.[17]

History

The Wappinger were hunter-gatherers, living in seasonal camps. They hunted game, fished the rivers and streams, collected shellfish, and gathered fruits, flowers, seeds, roots, nuts and honey.[18] They grew corn, beans, and various species of squash. By the time of contact first with Europeans in 1609, their settlements included camps along the major rivers, with larger villages located at the river mouths.[19] Settlements near fresh water and arable land could remain in one location for about twenty years, until the people moved to another place some miles away. Despite references to villages and other site types by early European explorers and settlers, few contact-period sites have been identified in southeastern New York (Funk 1976).[20]

European relations

The first contact with Europeans came in 1609, when Henry Hudson's expedition reached this area on the Half Moon.[21] The total population of the Wappinger people at that time has been estimated at between 3,000[17] and 13,200[22][20] individuals.

Robert Juet, an officer on the Half Moon, provides an account in his journal of some of the lower Hudson Valley Native Americans. In his entries for September 4 and 5, 1609, he says:

"This day the people of the country came aboord of us, seeming very glad of our comming, and brought greene tobacco, and gave us of it for knives and beads. They goe in deere skins loose, well dressed. They have yellow copper. They desire cloathes, and are very civill...They have great store of maize or Indian wheate whereof they make good bread. The country is full of great and tall oakes. This day [September 5, 1609] many of the people came aboord, some in mantles of feathers, and some in skinnes of divers sorts of good furres. Some women also came to us with hempe. They had red copper tabacco pipes and other things of copper they did wear about their neckes. At night they went on land againe, so wee rode very quite, but durst not trust them" (Juet 1959:28).[20]

Dutch navigator and colonist David Pieterz De Vries recorded another description of the Wappinger who resided around Fort Amsterdam:

"The Indians about here are tolerably stout, have black hair with a long, lock which they let hang on one side of the head. Their hair is shorn on the top of the head like a cock's comb. Their clothing is a coat of beaver skins over the body, with the fur inside in winter and outside in summer; they have, also, sometimes a bear's hide, or a coat of the skins of wild cats, or hefspanen [probably raccoon], which is an animal most as hairy as a wild cat, and is also very good to eat. They also wear coats of turkey feathers, which they know how to put together. Their pride is to paint their faces strangely with red or black lead, so that they look like fiends. Some of the women are very well featured, having long countenances. Their hair hangs loose from their head; they are very foul and dirty; they sometimes paint their faces, and draw a black ring around their eyes."[23]

As the Dutch began to settle in the area, they pressured the Connecticut Wappinger to sell their lands and seek refuge with other Algonquian-speaking tribes. The western bands, however, stood their ground amidst rising tensions.[24]

Following the Pavonia massacre by colonists, during Kieft's War in 1643, the remaining Wappinger bands united against the Dutch, attacking settlements throughout New Netherland. The Dutch responded with the March 1644 slaughter of between 500-700 members of Wappinger bands in the Pound Ridge Massacre, most burned alive in a surprise attack upon their sacred wintering ground. It was a severe blow to the tribe.

Allied with their trading partners, the powerful Mohawk of the Iroquois nations in central and western New York, the Dutch defeated the Wappinger by 1645.[25] The Mohawk and Dutch killed more than 1500 Wappinger in the two years of the war. This was a devastating toll for the Wappinger.[17]

The Wappinger faced the Dutch again in the 1655 Peach Tree War, a three-day engagement which left an estimated 100 settlers and 60 Wappinger dead, and strained relations further between the two groups.[26] After the war, the confederation broke apart, and many of the surviving Wappinger left their native lands for the protection of neighboring tribes, settling in particular in the "prayer town"[27] Stockbridge, Massachusetts in the western part of the colony, where Natives had settled who had converted to Christianity.

In 1765, the remaining Wappinger in Dutchess County sued the Philipse family for control of the Philipse Patent land[lower-alpha 2] but lost. In the aftermath the Philipses raised rents on the European-American tenant farmers, sparking colonist riots across the region.[28][29]

%2C_border_cropped.jpg)

In 1766 Daniel Nimham, last sachem of the Wappinger, was part of a delegation that traveled to London to petition the British Crown for land rights and better treatment by the American colonists. Britain had controlled former "Dutch" lands in New York since 1664. Nimham was then living in Stockbridge, but he was originally from the Wappinger settlement of Wiccopee, New York,[30] near what the Dutch had developed as Fishkill on the Hudson.[31] He argued before the royal Lords of Trade, who were generally sympathetic to his claims, but did not arrange for the Wappinger to regain any land after he returned to North America.

The Lords of Trade reported that there was sufficient cause to investigate

"frauds and abuses of Indian lands...complained of in the American colonies, and in this colony in particular." And that, "the conduct of the lieutenant-governor and the council...does carry with it the colour of great prejudice and partiality, and of an intention to intimidate these Indians from prosecuting their claims."

Upon a second hearing before New York Provincial Governor Sir Henry Moore and the Council, John Morin Scott argued that legal title to the land was only a secondary concern. He said that returning the land to the Indians would set an adverse precedent regarding other similar disputes.[32] Nimham did not give up the cause. When the opportunity to serve with the Continental Army in the American Revolution arose, he chose it over the British in the hopes of receiving fairer treatment by the American government in its aftermath. It was not to be.

In the American Revolution

Many Wappinger served in the Stockbridge Militia during the American Revolution. Nimham, his son and heir Abraham, and some forty warriors were killed or mortally wounded in the Battle of Kingsbridge in the Bronx on August 30, 1778. It proved an irrevocable blow to the tribe, which had also been decimated by European diseases.[33]

Decline

Following the war, most of the surviving Wappinger moved west to join the Algonquian Stockbridge-Munsee tribe in Ohio. From that time the Wappinger ceased to have an independent name in history, and their people intermarried with others. A few scattered remnants still remained. As late as 1811, a small band was recorded as having a settlement on a low tract of land by the side of a brook, under a high hill in the northern part of the Town of Kent in Putnam County.[33] Later in the early 19th century, the Stockbridge-Munsee in Ohio were forced to remove to Wisconsin. Today, members of the federally recognized Stockbridge-Munsee Nation reside mostly there on a reservation.

Bands

While Edward Manning Ruttenber suggested in 1872 that there had been a Wappinger Confederacy, as did anthropologist James Mooney in 1910, Ives Goddard contests their view. He writes that no evidence supports this idea.[7]

The suggested bands of the Wappinger, headed by sachems, have been described as including:

Wappinger (proper)

- Wappinger who lived on the east side of the Hudson River in present-day Dutchess County, New York

Hammonasset

- Hammonasset, an eastern group at the mouth of the Connecticut River, in present-day Middlesex County, Connecticut

Kitchawank

- Kitchawank, lived in northern Westchester County, New York in the area of Croton-on-Hudson, New York, site of the oldest oyster-shell middens found on the North Atlantic Coast. There they built a large, fortified village, called Navish, at the neck of Croton Point.[34]

Massaco

- Massaco, along the Farmington River in Connecticut

Nochpeem

- Nochpeem, in southern portions of present-day Dutchess County, New York

Paugusset

- Paugusset, along the Housatonic River, present-day eastern Fairfield and western New Haven counties of Connecticut

Podunk

- Podunk, east of the Connecticut River in eastern Hartford County, Connecticut

Poquonock

- Poquonock, western present-day Hartford County, Connecticut

Quinnipiac

- Quinnipiac, in central New Haven County, Connecticut

Sicaog

- Sicaog, in present-day Hartford County, Connecticut

Sintsink

Siwanoy

- Siwanoy, southeast coastal Westchester County, New York, into southwestern Fairfield County, Connecticut

Tankiteke

- Tankiteke, also "Pachami" and "Pachani",[36] central coastal and extreme western Fairfield County, Connecticut north into eastern Putnam County and Dutchess County, New York[37]

Tunxis

- Tunxis, southwestern Hartford County, Connecticut

Wangunk

Sometimes called the "Mattabesset", the Wangunk lived in the Mattabesset area in central Connecticut. Originally located around Hartford and Wethersfield but they were displaced by settlers there, and relocated to land around the oxbow bend in the Connecticut River.[38]

Wecquaesgeek

- Wecquaesgeek (Wiechquaeskeck, Wickquasgeck, Weckquaesgeek), southwestern Westchester County, New York,[39] centered around the area of present-day Dobbs Ferry.[34]

{{stack|float=right|

.jpg)

Legacy

The Wappinger are the namesake of several areas in New York, including:

- Town of Wappinger

- Village of Wappingers Falls

- Wappinger Creek

- Wappinger Trail, Briarcliff Manor, New York

Broadway in New York City also follows their ancient trail.[40]

Notes

- They are referred to as Munsee, one of the Lenape dialect groups, by author Hauptman (2017)

- Then part of Dutchess County, but subsequently all of Putnam County, New York

References

- Sebeok 1977, p. 380.

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Wappinger

- Boesch, Eugene, J., Native Americans of Putnam County

- Ruttenber, E.M. (1906). "Footprints of the Red Men: Indian Geographical Names in the Valley of Hudson's River, the Valley of the Mohawk, and on the Delaware: Their location and the probable meaning of some of them". Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association - the Annual Meeting, with Constitution, By-Laws and List of Members. New York State Historical Association. 7th Annual: 40 (RA1–PA38). Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- Ruttenber, E. M. (1872). History of the Indian Tribes of Hudson's River. Albany, N.Y.: J. Munsell. p. 50.

- Hodge, Frederick Webb, ed. (October 1912). Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Part 2 (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. pp. 913, 1167, 1169. ISBN 978-1-4286-4558-5. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- Goddard 1978, p. 238.

- Sebeok 1977, p. 307.

- Sebeok 1977, p. 310.

- Sebeok 1977, p. 309.

- Sebeok 1977, p. 325.

- Brodhead, John Romeyn, Agent (1986) [First Pub. 1855]. O'Callaghan, E.B. (ed.). London Documents: XVII-XXIV. 1707-1733. Documents relative to the colonial history of the State of New York procured in Holland, England and France. Vol. 5. Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons & Co. ISBN 0-665-53988-6. OL7024110M. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- Pritchard, Evan T. (April 12, 2002). Native New Yorkers, the legacy of the Algonquin people of New York. Council Oaks Distribution. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-57178-107-9. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- Bright, William (November 30, 2007). Native American placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 548. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- Swanton 1952, p. 48.

- Vasiliev, Ren (2004). From Abbotts to Zurich: New York State Placenames. Syracuse University Press. p. 233. ISBN 0-8156-0798-9.

- Trelease, Allen (1997). Indian Affairs in Colonial New York. ISBN 0-8032-9431-X.

- "The Wappinger Indians", Mount Gulian Historic Site

- MacCracken 1956:266

- Eugene J. Boesch, Native Americans of Putnam County

- Swanton 1952, p. 47.

- Cook 1976:74

- Boyle, David (1896). "Short Historical and Journale Notes by David Pietersz, De Vries, 1665". Annual Archæological Report. Toronto: Warwick Bros. & Rutter. 1894–95: 75.

- Pauls, Elizabeth Prine (2010). "Wappinger". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- Axelrod, Alan (2008). Profiles in Folly. Sterling Publishing Company. pp. 229–236. ISBN 1-4027-4768-3.

- Reitano, Joanne R. (2006). The Restless City: A Short History of New York from Colonial Times to the Present. CRC Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-415-97849-1.

- Hauptman (2017)

- Kammen, Michael (1996). Colonial New York: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 302. ISBN 0-19-510779-9.

- Steele, Ian K. (2000). The Human Tradition in the American Revolution. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 85–91. ISBN 0-8420-2748-3.

- Grumet, Robert S. "The Nimhams of the Colonial Hudson Valley 1667-1783", The Hudson River Valley Review, The Hudson River Valley Institute

- Vaughan, Alden (2006). Transatlantic Encounters: American Indians in Britain, 1500-1776. Cambridge University Press. p. 177. ISBN 0-521-86594-8.

- Smolenski, John. and Humphrey, Thomas J., New World Orders: Violence, Sanction, and Authority in the Colonial Americas, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013 ISBN 9780812290004

- Historical and Genealogical Record Dutchess and Putnam Counties, New York, Press of the A. V. Haight Co., Poughkeepsie, New York, 1912; pp. 62-79 "In this fray the power of the tribe was forever broken. More than forty of the Indians were killed or desperately wounded."

- Levine, David. "Discover the Hudson Valley's Tribal History", Hudson Valley Magazine, June 24, 2016

- "1638- Colonists from Massachusetts Met the Quinnipiac Indians", The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut

- Wappinger History, Lee Saltzman

- Swanton 1952:Tankitele mainly in Fairfield County, Connecticut, between Five Mile River and Fairfield, extending inland to Danbury and even into Putnam and Dutchess Counties

- Grant-Costa, Paul (2015). "The Wangunk Reservation". Yale Indian Papers Project. Yale University. Retrieved Dec 15, 2015.

- Cohen, Doris Darlington. "The Weckquaesgeek" (PDF). Ardsley Historical Society.

- Dunlap, David W. (1983-06-15). "Oldest Streets Are Protected as Landmark". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

Bibliography

- Goddard, Ives (1978). "Delaware". In Trigger, Bruce G. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast, Vol. 15. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0-1600-4575-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hauptman, Laurence M (2017). "The Road to Kingsbridge: Daniel Nimham and the Stockbridge Indian Company in the American Revolution". American Indian. Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian. 18 (3): 34–39.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sebeok, Thomas, ed. (1977). Native Languages of the Americas, Volume 2. Springer. p. 380. ISBN 978-1-4757-1562-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swanton, John Reed (1952). The Indian Tribes of North America. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Books. ISBN 978-0-8063-1730-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)