Wanggongchang Explosion

The Wanggongchang Explosion (Chinese: 王恭廠大爆炸), also known as the Great Tianqi Explosion (天啟大爆炸), Wanggongchang Calamity (王恭廠之變) or Beijing Explosive Incident in Late Ming (晚明北京爆炸事件), was an unexplained catastrophic explosion that occurred on May 30, 1626 AD during the late reign of Tianqi Emperor, at the heavily populated Ming China capital Beijing,[1] and had reportedly killed around 20,000 people. The nature of the explosion is still unclear to this day, as it is estimated to have released energy equivalent to about 10-20 kiloton of TNT, similar to that of the Hiroshima bombing.

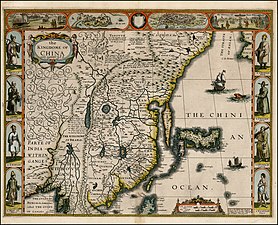

Map of China in 1626 | |

| Date | May 30, 1626 |

|---|---|

| Location | Beijing, China |

| Casualties | |

| Possibly as many as 20,000 | |

History

Background

The Wanggongchang Armory was located about 3 kilometres (1.9 miles) southwest of the Forbidden City, in modern-day central Xicheng District. It was one of the six gunpowder factories administered by the Ministry of Works in the Beijing area, and also one of the main storage facilities of armors, firearms, bows, ammunitions and gunpowders for the Shenjiying defending the capital. It was normally staffed by 70 to 80 personnel.

Explosion

The most detailed account of the explosion was from a contemporary official gazette named Official Notice of Heavenly Calamity (Chinese: 天變邸抄; pinyin: Tiānbiàn Dĭchāo). The explosion reportedly took place at Sì shi (between 9 and 11 o'clock) on the late morning of May 30, 1626. The sky was clear, but suddenly a loud "roaring" rumble was heard coming from northeast, gradually reached southwest of the city, and was followed by dust clouds and shaking of houses. Then a bright streak of flash containing a "great light" followed and a huge bang that "shattered the sky and crumbled the earth" occurred, the sky turned dark, and everything within the 3-4 li (about 2 km or 1.2 miles) vicinity and a 13 square li (about 4 km2 or 1.5 mi2) area was utterly obliterated. The streets were unrecognizable, littered with fragmented bodies and showered with falling roof tiles. The force of the explosion was so great that large trees were uprooted and found to be thrown as far as the rural Miyun on the opposite side of the city, and a 5,000-catty (about 3 metric tons) stone lion was thrown over the city wall.[2] The noise of the blast was heard as far as Tongzhou to the east, Hexiwu to the south, and Miyun and Changping to the north, and tremblings were felt over 150 km away in Zunhua, Xuanhua, Tianjin, Datong and Guangling. The ground around the immediate vicinity of Wanggongchang Armory, the epicenter of the explosion, had sunken for over 2 zhangs (about 6.5 m or 21 feet), but there was a notable lack of fire damage. The clouds over the epicenter were also reported to be strange: some looked like messy strands of silk, some were multi-coloured, while some "looked like a black lingzhi", rising into the sky and did not disperse until hours later.

Several government officials in the city had been killed, injured or gone missing during the explosion, and some were reportedly buried alive at their own home. The Minister of Works Dong Kewei (董可威) broke both arms and later had to retire from politics completely. The palaces in the Forbidden City were under renovation at the time, and over 2,000 workers were shaken off the roof, falling to their deaths. Tianqi Emperor himself was having breakfast in Qianqing Palace when the explosion happened, and after the initial quake all the palace servants panicked with fear, so the emperor started running to the Hall of Union followed only by a single guard who remained calm, but the guard was later killed by a falling tile. Tianqi Emperor's only remaining heir, the 7-month-old Crown Prince Zhu Cijiong (朱慈炅), died from the shock.[2]

Thousands of houses were destroyed, and more than 20,000 people perished. Survivors later reported broken rocks, timber, body parts of men and animals raining down from the sky for hours, especially near Desheng Gate, but the bodies of victims however were later found to be all naked with their clothes mysteriously stripped off. Rice grain-sized metal drosses were reported to have fallen near Xi'an Gate, and clothes were sent flying and falling on treetops to the countrysides. Hundreds of houses in as far as Jizhou had also collapsed from the quake of the explosion.

Aftermath

The late Ming Dynasty was already suffering domestic crisis from political corruption, factional conflicts, and repeated natural disasters (proposed to be due to the Little Ice Age by some historians) leading to peasant riots and rebellions. However, the horror of the Wanggongchang Explosion dwarfed all of those, and the imperial courts criticized the Tianqi Emperor and believed that the incident was a punishment from Heaven as a warning to correct the sins of the emperor's personal incompetence. Tianqi Emperor was forced to publicly announce a repending edict, and issued 20,000 taels of gold for the rescue and relief effort.

Sociopolitical impact

The Wanggongchang Explosion can be considered a pivotal event in the early modern Chinese history, for multiple reasons. The destruction of the Wanggongchang Armory, one of the largest stockpiles and manufacturing facilities of firearm and ammunition, resulted in a hardware loss that the Ming military never recovered from. The gold issued for the relief effort put further strain on the Ming government budget, which was already suffering from ever increasing military expenditures in Manchuria against the Jurchen rebellion by Nurhaci, as well as rampant tax resistance by the upper middle class in the more affluent South. The superstitious belief that the incident was a heavenly punishment for the personal failing of the Tianqi Emperor (who was more motivated in carpentry than ruling the country) also further eroded the authority and public respect towards the Ming monarchy.

Furthermore, the Wanggongchang Explosion resulted in the death of the Tianqi Emperor's only surviving son, Crown Prince Zhu Cijiong, leaving him heirless. Tianqi himself would die the following year, and his overambitious younger brother Prince Zhu Youjian inherited the throne as the Chongzhen Emperor. Chongzhen, who hated the powerful chief eunuch Wei Zhongxian intensely, soon purged Wei,[3] which ironically removed a stabilizing factor within the Ming court. The factional infighting between the resurgent Donglin faction (who were previously persecuted brutally by Wei) and their various political opponents would then intensify during Chongzhen's reign, coupling with Chongzhen's own impatience and rash decisions, would further accelerate the decline and eventual fall of the Ming dynasty 18 years later.

Possible causes

The cause of the explosion has never been conclusively determined. Although there are multiple sources of detailed historical records, the incident happened well before the proliferation of modern science in China, and contemporary interpretations are compounded with superstitious speculations. There were also suspicions that the official account might have been exaggerated with tints of yellow journalism. Throughout the ages, various theories have been put forth, including gunpowder explosion, meteorite air burst, natural gas explosion and volcanic eruption,[2] as well as outlandish theories like nuclear explosion and even alien attack, etc. Despite some hypotheses being regarded as scientifically plausible, no academic consensus has been reached.

Gunpowder

Due to the epicenter of the disaster, the Wanggongchang Armory, being a military storage facility that "dispatches 3000 catties of gunpowder every five days", an accidental gunpowder ignition was blamed as the culprit from the very beginning. The cause has been suspected to be poor handling during manufacturing and transport, electrostatic discharges or even sabotage by Later Jin spies, and sometimes cited as proof of the decline in the Ming government's administrative quality.

While seemingly an obvious and convenient explanation, the lack of burning damage at ground zero and the unexplained stripping of victims' clothing (which were then found mostly unburnt and blown miles away), noted by multiple historical records, both indicated more likely an overpressure rather than combustive nature of the explosion. The gunpowder hypothesis also fails to explain the alleged sound and rumbling that came from the northeast prior to the actual explosion, and is insufficient in justifying the destructive power of the explosion. Although in large quantities gunpowder can produce enough energy to create a mushroom cloud, black powders deflagrates rather than detonates, and might have difficulty producing sufficient energy intensity to cave in the ground by 6 meters, uproot and throw large trees to miles away and launch a 3-ton stone lion over a city wall. From the historical description of the damage, the explosion would need the TNT equivalent on par with the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Bolide

The bolide hypothesis argues that the description and magnitude of the explosion is more consistent with a meteor exploding mid-air at low/medium altitude while entering the Earth's atmosphere, and the Wanggongchang Armory, even if its stored gunpowder had exploded, was merely an innocent victim of the much more powerful air burst.

Many historians dismissed the talk of a meteorite strike on the basis that no evidence of the classic impact crater was found, and the description of an alleged mushroom cloud seems to suggest another cause for the explosion. However, the descriptions of a preceding flash, roaring sound and rumbling, and showering of rocks and grains of metal, bear resemblance to modern records of exploding bolides (such as the well witnessed 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor). Description of the blast aftermath can also find some resemblance to Leonid Kulik's finding of the air burst obliteration of Siberian forests by the Tunguska event three centuries later. Coincidentally, the Tunguska event, which was a 10-30 megaton airburst (more than 1,000 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb) in the upper middle troposphere (at 5–10 km above the surface) that also didn't leave any impact craters, was also subjected to various outlandish theories (such as nuclear tests, alien weaponry or even superexperiments by Nikola Tesla) until scientific consensus favored the explanation of a bolide explosion and dismissed most other hypotheses.

Another notable issue is the "mushroom cloud" witnessed after the explosion was actually specifically described in historical records as resembling a Chinese lingzhi (Ganoderma lucidum), which is usually more fan-shaped like an upward-facing shower head rather than the more umbrella-like shape of a typical mushroom, suggesting an explosion likely occurring mid-flight rather than arising from the ground. The description of other multi-colored, "messy silk" type clouds also have resemblance to the smoke trails of exploding mid-air bolides witnessed in modern times.

If the bolide hypothesis is proven to be true, the Wanggongchang Explosion would be the most lethal impact event in recorded history (surpassing the 1490 Ch'ing-yang event).

Earthquake

The area around Beijing is not impervious to earthquakes, with more than a hundred confirmed earthquakes during the Ming dynasty in historical records. The description of the rumbling vibration before, and during the explosion did resemble earthquake in some way. However, many structures not too far away (such as the Cheng'en Temple) suffered little to no damage, which was very unlikely considering the extent of damage suffered at the epicenter. The earthquake hypothesis also fails to explain the presence of mushroom cloud and the clothes-stripping of victims, nor does it explain objects being sent flying miles away.

Tornado

A powerful tornado can be sudden and highly destructive, and tends to occur in late spring and early summer, and can certainly send objects flying to miles away, though it might be questionable to suggest a tornado threw a 3-ton stone lion over a city wall. It would also be very unlikely for a tornado to suddenly appear out of nowhere without some type of buildup, and the tornado hypothesis failed to adequately explain the loud bang and quake felt up to a hundred miles away.

References

- Feng, Naixi (2020-06-09). "Mushroom Cloud Over the Northern Capital: Writing the Tianqi Explosion in the Seventeenth Century". Late Imperial China. 41 (1): 71–112. doi:10.1353/late.2020.0001. ISSN 1086-3257.

- Guojian Liang, Lang Deng (29 April 2013). "Solving a Mystery of 400 Years-An Explanation to the "explosion" in Downtown Beijing in the Year of 1626". allbestessays.com. Retrieved 20 December 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- John W. Dardess, Blood and History in China: The Donglin Faction and its Repression (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2002), 154.