House of Wangchuck

The House of Wangchuck (Tibetan: དབང་ཕྱུག་རྒྱལ་བརྒྱུད་, Wylie: Dbang-phyug Rgyal-brgyud ) has ruled Bhutan since it was reunified in 1907. Prior to reunification, the Wangchuck family had governed the district of Trongsa as descendants of Dungkar Choji. They eventually overpowered other regional lords and earned the favour of the British Empire. After consolidating power, the 12th Penlop of Trongsa Gongsar Ugyen Wangchuck was elected Druk Gyalpo ("Dragon King"), thus founding the royal house. The position of Druk Gyalpo is more commonly known in English as King of Bhutan.

| House of Wangchuck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | Bhutan |

| Founded | 17 December 1907 AD |

| Founder | Ugyen Wangchuck |

| Current head | Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck |

| Titles | |

| Religion | Vajrayana Buddhism |

| Bhutanese royal family |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Family of the Third Druk Gyalpo (deceased) HM The Queen Grandmother

|

|

Family of the Second Druk Gyalpo (deceased)

|

The Wangchuck dynasty ruled government power in Bhutan and established relations with the British Empire and India under its first two monarchs. The third, fourth, and fifth (current) monarchs have put the kingdom on its path toward democratization, decentralization, and development.

History

There have been five Wangchuck kings of Bhutan, namely:

- Ugyen Wangchuck (b.1861–d.1926) "First King"; reigned 17 December 1907 – 21 August 1926.

- Jigme Wangchuck (b.1905–d.1952) "Second King"; r. 21 August 1926 – 24 March 1952.

- Jigme Dorji Wangchuck (b.1929–d.1972) "Third King"; r. 24 March 1952 – 24 July 1972.

- Jigme Singye Wangchuck (b.1955) "Fourth King"; r. 24 July 1972 – 15 December 2006.

- Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck (b.1980) "Fifth King"; r. 14 December 2006 – present.

The ascendency of the House of Wangchuck is deeply rooted in the historical politics of Bhutan. Between 1616 and 1907, varying administrative, religious, and regional powers vied for control within Bhutan. During this period, factions were influenced and supported by Tibet and the British Empire. Ultimately, the hereditary Penlop of Trongsa, Ugyen Wangchuck, was elected the first Druk Gyalpo by an assembly of his subjects in 1907, marking the ascendency of the House of Wangchuck.

Origins

Under Bhutan's early theocratic Tibetan dual system of government, decreasingly effective central government control resulted in the de facto disintegration of the office of Shabdrung after the death of Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal in 1651. Under the dual system of the government, Desi or the temporal rulers took control of civil administration and Je Khenpos took control of religious affairs. Two successor Shabdrungs – the son (1651) and stepbrother (1680) of Ngawang Namgyal – were effectively controlled by the Druk Desi and Je Khenpo until power was further splintered through the innovation of multiple Shabdrung incarnations, reflecting speech, mind, and body. Increasingly secular regional lords (penlops and dzongpons) competed for power amid a backdrop of civil war over the Shabdrung and invasions from Tibet, and the Mongol Empire.[1] The penlops of Trongsa and Paro, and the dzongpons of Punakha, Thimphu, and Wangdue Phodrang were particularly notable figures in the competition for regional dominance.[1][2]

Chogyal Minjur Tenpa (1613–1680; r. 1667–1680) was the first Penlop of Trongsa (Tongsab), appointed by Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal. He was born Damchho Lhundrub in Min-Chhud, Tibet, and led a monastic life from childhood. Before his appointment as Tongsab, he held the appointed post of Umzey (Chant Master). A trusted follower of the Shabdrung, Minjur Tenpa was sent to subdue kings of Bumthang, Lhuntse, Trashigang, Zhemgang, and other lords from Trongsa Dzong. After doing so, the Tongsab divided his control in the east among eight regions (Shachho Khorlo Tsegay), overseen by Dungpas and Kutshabs (civil servants). He went on to build Jakar, Lhuntse, Trashigang, and Zhemgang Dzongs.[3]:106

Within this political landscape, the Wangchuck family originated in the Bumthang region of central Bhutan.[4] The family belongs to the Nyö clan, and is descended from Pema Lingpa, a Bhutanese Nyingmapa saint. The Nyö clan emerged as a local aristocracy, supplanting many older aristocratic families of Tibetan origin that sided with Tibet during invasions of Bhutan. In doing so, the clan came to occupy the hereditary position of Penlop of Trongsa, as well as significant national and local government positions.[5]

The Penlop of Trongsa managed central Bhutan; the rival Penlop of Paro controlled western Bhutan; and dzongpons controlled areas surrounding their respective dzongs. The Penlop of Paro, unlike Trongsa, was an office appointed by the Druk Desi's central government. Because western regions controlled by the Penlop of Paro contained lucrative trade routes, it became the object of competition among aristocratic families.[5]

Although Bhutan generally enjoyed favorable relations with both Tibet and British India through the 19th century, extension of British power at Bhutan's borders as well as Tibetan incursions in British Sikkim defined politically opposed pro-Tibet and pro-Britain forces.[6] This period of intense rivalry between and within western and central Bhutan, coupled with external forces from Tibet and especially the British Empire, provided the conditions for the ascendancy of the Penlop of Trongsa.[5]

After the Duar War with Britain (1864–65) as well as substantial territorial losses (Cooch Behar 1835; Assam Duars 1841), armed conflict turned inward. In 1870, amid the continuing civil wars, the 10th Penlop of Trongsa, Jigme Namgyal ascended to the office of 48th Druk Desi. In 1879, he appointed his 17-year-old son Ugyen Wangchuck as the 23rd Penlop of Paro. Jigme Namgyal reigned through his death 1881, punctuated by periods of retirement during which he retained effective control of the country.[7]

The pro-Britain Penlop Ugyen Wangchuck ultimately prevailed against the pro-Tibet and anti-Britain Penlop of Paro after a series of civil wars and rebellions between 1882 and 1885. After his father's death in 1881, Ugyen Wangchuck entered a feud over the post of Penlop of Trongsa. In 1882, at the age of 20, he marched on Bumthang and Trongsa, winning the post of Penlop of Trongsa in addition to Paro. In 1885, Ugyen Wangchuck intervened in a conflict between the Dzongpens of Punakha and Thimphu, sacking both sides and seizing Simtokha Dzong. From this time forward, the office of Desi became purely ceremonial.[7]

Nationhood under the Wangchucks

The 12th Trongsa Penlop, Ugyen Wangchuck, firmly in power and advised by Kazi Ugyen Dorji, accompanied the British expedition to Tibet as an invaluable intermediary, earning his first British knighthood. Penlop Ugyen Wangchuck further garnered knighthood in the KCIE in 1905. Meanwhile, the last officially recognized Shabdrung and Druk Desi had died in 1903 and 1904, respectively. As a result, a power vacuum formed within the already dysfunctional dual system of government. Civil administration had fallen to the hands of Penlop Ugyen Wangchuck, and in November 1907 he was unanimously elected hereditary monarch by an assembly of the leading members of the clergy, officials, and aristocratic families. His ascendency to the throne ended the traditional dual system of government in place for nearly 300 years.[6][8] The title Penlop of Trongsa – or Penlop of Chötse, another name for Trongsa – continued to be held by crown princes.[9]

As King of Bhutan, Ugyen Wangchuck secured the Treaty of Punakha (1910), under which Britain guaranteed Bhutan's independence, granted Bhutanese Royal Government a stipend, and took control of Bhutanese foreign relations. After his coronation, Uygen further merited the British Delhi Durbar Gold Medal in 1911; the Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India (KCSI) in 1911; and the Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (GCIE) in 1921. King Ugyen Wangchuck died in 1926.

The reign of the Second King Jigme Wangchuck (1926–1952) was characterized by an increasingly powerful central government and the beginnings of infrastructure development. Bhutan also established its first diplomatic relations with India under the bilateral Treaty of Friendship, largely patterned after the prior Treaty of Punakha.[10]

The Third King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck (r. 1952–1972) ascended the throne at the age of 16, having been educated in England and India. During the reign of the Third King, Bhutan began further political and legal reforms and started to open to the outside world.[7] Notably, the Third King was responsible for establishing a unicameral National Assembly in 1953 and establishing relations with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1958. Under Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, Bhutan also modernized its legal codes.[11]

Democratization under the Wangchucks

The Third King died in 1972, and the Raven Crown passed to the 16-year-old Jigme Singye Wangchuck. The Fourth King was, like his father, educated in England and India, and had also attended Ugyen Wangchuck Academy at Satsham Choten in Paro. Reigning until 2006, the Fourth King was responsible for the development of the tourism industry, Gross National Happiness as a concept, and strides in democratization including the draft Constitution of Bhutan. The later years of his reign, however, also marked the departure of Bhutanese refugees in the 1990s amid the government's driglam namzha policy (official behaviour and dress code) and citizenship laws that were overzealously enforced by some district officials. To the surprise of the Bhutanese public, the Fourth King announced his abdication in 2005 and retired in 2006, handing the crown to his son Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck.[7]

Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck assumed the throne as the Fifth King in 2008 as the kingdom adopted its first democratic Constitution.

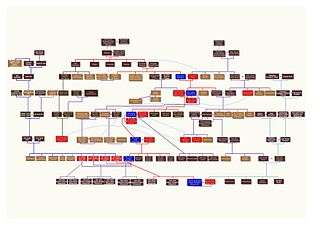

Genealogy

Below is an extended patrilineal genealogy of the House of Wangchuck through the present monarch.

| Name | Birth | Death | Reign start |

Reign end | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romanization | Wylie transliteration | Dzongkha | ||||

| Sumthrang Chorji | Sum-phrang Chos-rje | སུམ་ཕྲང་ཆོས་རྗེ་ | 1179 | 1265 | ||

| Zhigpo Tashi Sengye | Zhig-po bKra-shis Seng-ge | ཞིག་པོ་བཀྲ་ཤིས་སེང་གེ་ | 1237 | 1322 | ||

| Bajra Duepa | Bajra 'Dus-pa | བཇ་ར་འདུས་པ་ | 1262 | 1296 | ||

| Depa Paljor | bDe-pa'i dPal-'byor | བདེ་པའི་དཔལ་འབྱོར་ | 1291 | 1359 | ||

| Palden Sengye | dPal-den Seng-ge | དཔལ་དེན་སེང་གེ་ | 1332 | 1384 | ||

| Tenpa Nyima[nb 1] | bsTan-pa'i Nyi-ma | བསྟན་པའི་ཉི་མ་ | 1382 | |||

| Dongrub Zangpo | Don-grub bZang-po | དོན་གྲུབ་བཟང་པ་ | ||||

| Pema Lingpa | Padma Gling-pa | པདྨ་གླིང་པ་ | 1450 | 1521 | ||

| Khochun Chorji | mKho-chun Chos-rje | མཁོ་ཆུན་ཆོས་རྗེ་ | 1505 | |||

| Ngawang | Ngag-dbang | ངག་དབང་ | 1539 | |||

| Gyalba | rGyal-ba | རྒྱལ་བ་ | 1562 | |||

| Dungkar Choji[nb 2] | Dun-dkar Chos-rje | དུན་དྐར་ཆོས་རྗེ་ | 1578 | |||

| Tenpa Gyalchen | bsTan-pa'i rGyal-mchan | བསྟན་པའི་རྒྱལ་མཆན་ | 1598 | 1694 | ||

| Tenpa Nyima | bsTan-pa'i Nyi-ma | བསྟན་པའི་ཉི་མ་ | 1623 | 1689 | ||

| Dadrag | Zla-grags | ཟླ་གྲགས | 1641 | |||

| Tubzhong | gTub-zhong | གཏུབ་ཞོང་ | 1674 | |||

| Pema Rije | Padma Rig-rgyas (Pemarigyas) | པདྨ་རིག་རྒྱས་ | 1706 | 1763 | ||

| Rabje | Rab-rgyas (Rabgyas) | རབ་རྒྱས་ | 1733 | |||

| Pema | Padma | པདྨ་ | ||||

| Dasho Pila Gonpo Wangyal | Pi-la mGon-po rNam-rgyal | པི་ལ་མགན་པོ་རྣམ་རྒྱལ་ | 1782 | |||

| Dasho Jigme Namgyal | rJigs-med rNam-rgyal | འཇིགས་མེད་རྣམ་རྒྱལ་ | 1825 | 1881 | ||

| King Ugyen Wangchuck | O-rgyan dBang-phyug | ཨོ་རྒྱན་དབང་ཕྱུག་ | 1862 | 1926 | 1907 | 1926 |

| King Jigme Wangchuck | 'Jigs-med dBang-phyug | འཇིགས་མེད་དབང་ཕྱུག་ | 1905 | 1952 | 1926 | 1952 |

| King Jigme Dorji[nb 3]Wangchuck | 'Jigs-med rDo-rje dBang-phyug | འཇིགས་མེད་རྡོ་རྗེ་དབང་ཕྱུག་ | 1928 | 1972 | 1952 | 1972 |

| King Jigme Singye Wangchuck | 'Jigs-med Seng-ge dBang-phyug | འཇིགས་མེད་སེང་གེ་དབང་ཕྱུག་ | 1955 | – | 1972 | 2006 |

| King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck | 'Jigs-med Khe-sar rNam-rGyal dBang-phyug | འཇིགས་མེད་གེ་སར་རྣམ་རྒྱལ་དབང་ཕྱུག་ | 1980 | – | 2006 | – |

See also

Notes

- Brother of Jamjeng Dragpa Oezer (Jam-dbyangs Grags-pa Od-zer) (1382–1442)

- Wangchuck forefathers may be referred to as of the Dungkar Choji family

- A member of the Dorji family through his mother

References

-

-

- Dorji, Chen-Kyo Tshering (1994). "Appendix III". History of Bhutan based on Buddhism. Sangay Xam, Prominent Publishers. p. 200. ISBN 81-86239-01-4. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- Crossette, Barbara (2011). So Close to Heaven: The Vanishing Buddhist Kingdoms of the Himalayas. Vintage Departures. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 0-307-80190-X. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- (Gter-ston), Padma-gliṅ-pa; Harding, Sarah (2003). Harding, Sarah (ed.). The life and revelations of Pema Lingpa. Snow Lion Publications. p. 24. ISBN 1-55939-194-4. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Europa Publications (2002). Far East and Australasia. Regional surveys of the world: Far East & Australasia (34 ed.). Psychology Press. pp. 180–81. ISBN 1-85743-133-2. Retrieved 2011-08-08.

- Brown, Lindsay; Mayhew, Bradley; Armington, Stan; Whitecross, Richard W. (2007). Bhutan. Lonely Planet Country Guides (3 ed.). Lonely Planet. pp. 38–43. ISBN 1-74059-529-7. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

-

- Rennie, Frank; Mason, Robin (2008). Bhutan: Ways of Knowing. IAP. p. 176. ISBN 1-59311-734-5. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Global Investment and Business Center, Inc. (2000). Bhutan Foreign Policy and Government Guide. World Foreign Policy and Government Library. 20. Int'l Business Publications. pp. 59–61. ISBN 0-7397-3719-8. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- United Nations. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (2004). Perspectives from the ESCAP region after the Fifth WTO Ministerial Meeting. ESCAP Studies in Trade and Investment. 53. United Nations Publications. p. 66. ISBN 92-1-120404-6.

External links

- "Bhutan's Royal Family". RAO online. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Official Site

- Official Facebook