Kurmaed Province

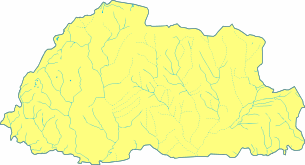

Kurmaed Province (Dzongkha: ཀུར་སྨད་; Wylie: kur-smad; "Lower Kur") was one of the nine historical Provinces of Bhutan.[1]

Kurmaed Province occupied lands in southeastern Bhutan. It was administered jointly with Kurtoed Province. By the 19th century, the ruling governor had become subordinate to the Penlop of Trongsa, who wielded effective power throughout eastern Bhutan.[1][2]

History

Under Bhutan's early theocratic dual system of government, decreasingly effective central government control resulted in the de facto disintegration of the office of Zhabdrung after the death of Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal in 1651. Under this system, the Zhabdrung reigned over the temporal Druk Desi and religious Je Khenpo. Two successor Zhabdrungs – the son (1651) and stepbrother (1680) of Ngawang Namgyal – were effectively controlled by the Druk Desi and Je Khenpo until power was further splintered through the innovation of multiple Zhabdrung incarnations, reflecting speech, mind, and body. Increasingly secular regional lords (penlops and dzongpons) competed for power amid a backdrop of civil war over the Zhabdrung and invasions from Tibet, and the Mongol Empire.[3] The penlops of Trongsa and Paro, and the dzongpons of Punakha, Thimphu, and Wangdue Phodrang were particularly notable figures in the competition for regional dominance.[3][4] During this period, there were a total of nine provinces and eight penlops vying for power.[5]

Traditionally, Bhutan comprised nine provinces: Trongsa, Paro, Punakha, Wangdue Phodrang, Daga (also Taka, Tarka, or Taga), Bumthang, Thimphu, Kurtoed (also Kurtoi, Kuru-tod), and Kurmaed (or Kurme, Kuru-mad). The Provinces of Kurtoed and Kurmaed were combined into one local administration, leaving the traditional number of governors at eight. While some lords were Penlops, others held the title Dzongpen (Dzongkha: རྗོང་དཔོན་; Wylie: rjong-dpon; also "Jongpen," "Dzongpön"); both titles may be translated as "governor."[1]

Chogyal Minjur Tenpa (1613–1680; r. 1667–1680) was the first Penlop of Trongsa (Tongsab), appointed by Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal. He was born Damchho Lhundrub in Min-Chhud, Tibet, and led a monastic life from childhood. Before his appointment as Tongsab, he held the appointed post of Umzey (Chant Master). A trusted follower of the Zhabdrung, Minjur Tenpa was sent to subdue kings of Bumthang, Lhuntse, Trashigang, Zhemgang, and other lords from Trongsa Dzong. After doing so, the Tongsab divided his control in the east among eight regions (Shachho Khorlo Tsegay), overseen by Dungpas and Kutshabs (civil servants). He went on to build Jakar, Lhuentse, Trashigang, and Zhemgang Dzongs.[6]:106

The 10th Penlop of Trongsa Jigme Namgyel (r. 1853–1870) began consolidating power, paving the way for his son the 12th Penlop of Trongsa (and 21st Penlop of Paro) Ugyen Wangchuck to prevail in battle against all rival penlops and establish the monarchy in 1907. With the establishment of the monarchy and consolidation of power, the traditional roles of provinces, their rulers, and the dual system of government came to an end.[7][8]

References

- Madan, P. L. (2004). Tibet, Saga of Indian Explorers (1864–1894). Manohar Publishers & Distributors. pp. 77 et seq. ISBN 81-7304-567-4. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- White, J. Claude (1909). Sikhim & Bhutan: Twenty-One Years on the North-East Frontier, 1887–1908. New York: Longmans, Green & Co. pp. 11, 272–3, 301–10. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

-

-

- Lawrence John Lumley Dundas Zetland (Marquis of); Ronaldsha E., Asian Educational Services (2000). Lands of the Thunderbolt: Sikhim, Chumbi & Bhutan. Asian Educational Services. p. 204. ISBN 81-206-1504-2. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Dorji, C. T. (1994). "Appendix III". History of Bhutan based on Buddhism. Sangay Xam, Prominent Publishers. p. 200. ISBN 81-86239-01-4. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- Padma-gliṅ-pa (Gter-ston); Harding, Sarah (2003). Harding, Sarah (ed.). The life and revelations of Pema Lingpa. Snow Lion Publications. p. 24. ISBN 1-55939-194-4. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Brown, Lindsay; Mayhew, Bradley; Armington, Stan; Whitecross, Richard W. (2007). Bhutan. Lonely Planet Country Guides (3 ed.). Lonely Planet. pp. 38–43. ISBN 1-74059-529-7. Retrieved 2011-08-09.