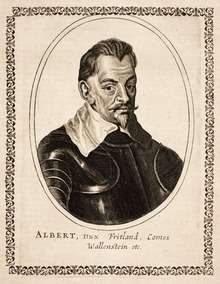

Albrecht von Wallenstein

Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Wallenstein (24 September 1583 – 25 February 1634), also von Waldstein (Czech: Albrecht Václav Eusebius z Valdštejna), was a Bohemian[lower-alpha 1] military leader and statesman who fought on the Catholic side during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). His successful martial career made him one of the richest and most influential men in the Holy Roman Empire by the time of his death. Wallenstein became the supreme commander of the armies of the Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand II and was a major figure of the Thirty Years' War.

Albrecht von Wallenstein | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 24 September 1583 (Old style: 14 September) |

| Died | 25 February 1634 (aged 50) Eger (now Cheb), Bohemia |

| Resting place | Mnichovo Hradiště (German: Münchengrätz) 50°31′17″N 14°58′25″E |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Imperial Army |

| Years of service | 1604–1634 |

| Rank | Generalissimo |

| Conflicts | Long Turkish War Uskok War

|

| Awards | Order of the Golden Fleece |

Wallenstein was born in the Kingdom of Bohemia into a poor Protestant noble family. He acquired a multilingual university education across Europe and converted to Catholicism in 1606. A marriage in 1609 to the wealthy widow of a Bohemian landowner gave him access to considerable estates and wealth after her death at an early age in 1614. Three years later, Wallenstein embarked on a career as a mercenary by raising forces for the Holy Roman Emperor in the War of Gradisca against the Republic of Venice.

Wallenstein fought for the Catholics in the Protestant Bohemian revolt of 1618 and was awarded estates confiscated from the rebels after their defeat at White Mountain in 1620. A series of military victories against the Protestants raised Wallenstein's reputation in the Imperial court and in 1625 he raised a large army of 50,000 men to further the Imperial cause. A year later, he administered a crushing defeat to the Protestants at Dessau Bridge. For his successes, Wallenstein became an Imperial count palatine and made himself ruler of the lands of the Duchy of Friedland in northern Bohemia.[2]

An imperial generalissimo[3] by land, and Admiral of the Baltic Sea from 21 April 1628,[4] Wallenstein found himself released from service in 1630 after Ferdinand grew wary of his ambition.[5] Several Protestant victories over Catholic armies induced Ferdinand to recall Wallenstein (Gollersdorf April 1632), who then defeated the Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus at Alte Veste and fought him to a draw at Fürth, the Swedish king was later killed at the Battle of Lützen. Wallenstein realised the war could last decades and, during the summer of 1633, arranged a series of armistices to negotiate peace. These proved to be his undoing as plotters accused him of treachery and Emperor Ferdinand II ordered his assassination. Dissatisfied with the Emperor's treatment of him, Wallenstein considered allying with the Protestants. However, he was assassinated at Eger in Bohemia by one of the army's officials, with the emperor's approval.

Early life

Wallenstein was born on 24 September 1583 in Heřmanice, Bohemia,[6] which is the easternmost and largest region in what was then the Holy Roman Empire, in the present-day Czech Republic, into a poor Protestant branch of the Waldstein (Wallenstein, Valdštejn) family[lower-alpha 2] who owned Heřmanice castle and seven surrounding villages.[6][7] His mother, Markéta Smiřická of Smiřice, died in 1593; his father, Vilém, died in 1595.[8]

They had raised him bilingually – the father spoke German while his mother preferred Czech – yet Wallenstein in his childhood had a better command of Czech than of German.[9] His parents' religious affiliations were Lutheranism and Utraquist Hussitism.[9] After their deaths, Albrecht for two years lived with his maternal uncle Heinrich (Jindřich) Slavata of Chlum and Košumberk, a member of the Unity of the Brethren (Bohemian Brethren), and adopted his uncle's religious affiliation.[9] His uncle sent him to the brethren's school at Košumberk Castle in Eastern Bohemia.

In 1597, Albrecht was sent to the Protestant Latin school at Goldberg (now Złotoryja) in Silesia, where the then-German environment led him to hone his German language skills.[9] While German became Wallenstein's lingua franca, he is said to have continued to curse in Czech.[10] On 29 August 1599, Wallenstein continued his education at the Protestant University of Altdorf near Nuremberg, Franconia, where he was often engaged in brawls and épée fights, leading to his imprisonment in the town prison.[9] He beat his servant so badly he had to purchase him a new suit of clothes on top of paying compensation.[11]

In February 1600,[9] Albrecht left Altdorf and travelled around the Holy Roman Empire, France and Italy,[12] where he studied at the universities of Bologna and Padua.[13] By this time, Wallenstein was fluent in German, Czech, Latin and Italian, was able to understand Spanish, and spoke some French.[9]

Wallenstein then joined the army of the Emperor Rudolf II in Hungary, where, under the command of Giorgio Basta, he saw two years of armed service (1604–1606) against the Ottoman Turks and Hungarian rebels.[14]

In 1604, his sister, Kateřina Anna, married the leader of the Moravian Protestants, Karel the Older of Zierotin.[15][16] He then studied at the University of Olomouc (matriculating in 1606). His contact with the Olomouc Jesuits is considered to be at least partially responsible for his conversion to Catholicism that same year.[12]

The contributory factor to his conversion may have been the Counter-Reformation policy of the Habsburgs that effectively barred Protestants from being appointed to higher offices at court in Bohemia and in Moravia, and the impressions he gathered in Catholic Italy.[17] However, there are no sources clearly indicating the reasons for Wallenstein's conversion, except for a subjunctive anecdote by his contemporary Franz Christoph von Khevenhüller about the Virgin Mary saving Wallenstein's life when he fell from a window in Innsbruck.[12] Wallenstein was later made a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

In 1607, based on recommendations by his brother-in-law, Zierotin, and another relative, Adam of Waldstein, often mistakenly referred to as his uncle, Wallenstein was made chamberlain at the court of Matthias, and later also chamberlain to archdukes Ferdinand and Maximilian.[18]

In 1609, Wallenstein married the Czech Lucretia of Víckov, née Nekšová, of Landek,[5] the wealthy widow of Arkleb of Víckov[19] who owned the towns of Vsetín, Lukov, Rymice and Všetuly/Holešov (all in eastern Moravia).[20] She was three years older than Wallenstein, and he inherited her estates after her death in 1614.[14]

He used his wealth to win favour, offering and commanding 200 horses for Archduke Ferdinand of Styria for his war with Venice in 1617, thereby relieving the fortress of Gradisca from the Venetian siege.[21] He later endowed a monastery in his late wife's name and had her reburied there.

In 1623, Wallenstein married Isabella Katharina, daughter of Count von Harrach. She bore him two children: a son who died in infancy and a surviving daughter.[14] Examples of the couple's correspondence survive. The two marriages made him one of the wealthiest men in the Bohemian Crown.

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War began in 1618 when the estates of Bohemia rebelled against Ferdinand of Styria and elected Frederick V, Elector Palatine, the leader of the Protestant Union, as their new king. Wallenstein associated himself with the cause of the Catholics and the Habsburg dynasty.

In the summer of 1618 Count Thurn led 10,000 troops into Moravia to secure their loyalty to the rebellion. Nobles who wished for a rapprochement with Ferdinand faced a choice. Senior nobleman Zierotin's son-in-law, Georg von Nachod, commanded the Moravian cavalry and his brother-in-law, Wallenstein, the infantry. Both decided to take their regiment into Austria. Nachod's troops rebelled and he fled for his life. Wallenstein's major demanded authorisation from the Estates upon which Wallenstein drew his sword and ran him through,"A fresh major was immediately appointed and displayed greater tractability".[11] Deserting the Bohemians, he marched his regiment to Vienna taking with him the Moravian treasury. There, however, the authorities told him that the money would go back to the Moravians – but he had shown his loyalty to Ferdinand, the future Emperor.

Wallenstein equipped a regiment of cuirassiers and won great distinction under Charles Bonaventure de Longueval, Count of Bucquoy in the wars against Ernst von Mansfeld and Gabriel Bethlen (both supporters of the Bohemian revolt) in Moravia. Wallenstein recovered his lands (which the rebels had seized in 1619) and after the Battle of White Mountain (8 November 1620) he secured the estates belonging to his mother's family and confiscated tracts of Protestant lands.

He grouped his new possessions into a territory called Friedland (Frýdlant) in northern Bohemia. A series of successes in battle led to Wallenstein becoming in 1622 an imperial count palatine, in 1623 a prince, and in 1625 Duke of Friedland.[22] Wallenstein proved an able administrator of the duchy[23] and sent a large representation to Prague to emphasize his nobility.

.jpg)

In order to aid Ferdinand (elected Holy Roman Emperor in 1619) against the Northern Protestants and to produce a balance in the Army of the Catholic League under Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, Wallenstein offered to raise a whole army for the imperial service following the bellum se ipsum alet principle, and received his final commission on 25 July 1625. Wallenstein's successes as a military commander brought him fiscal credit, which in turn enabled him to receive loans to buy lands, many of them being the former estates of conquered Bohemian nobles. He used his credit to grant loans to Ferdinand II, which were repaid through lands and titles.[24] Wallenstein's popularity soon recruited 30,000 (not long afterwards 50,000) men.[25] The two armies worked together over 1625–27, at first against Mansfeld.

Having beaten Mansfeld at Dessau (25 April 1626), Wallenstein cleared Silesia of the remnants of Mansfeld's army in 1627.[25][26]

At this time he bought from the emperor the Duchy of Sagan (in Silesia). He then joined Tilly in the struggle against Christian IV of Denmark,[27] and afterwards gained as a reward the Duchies of Mecklenburg, whose hereditary dukes suffered expulsion for having helped the Danish king. This awarding of a major territory to someone of the lower nobility shocked the high-born rulers of many other German states.[28]

Wallenstein assumed the title of "Admiral of the North and Baltic Seas". However, in 1628 he failed to capture Stralsund, which resisted the Capitulation of Franzburg and the subsequent siege with assistance of Danish, Scottish and Swedish troops, a blow that denied him access to the Baltic and the chance to challenge the naval power of the Scandinavian kingdoms and of the Netherlands.[26]

Although he succeeded in defeating Christian IV of Denmark in the Battle of Wolgast and neutralizing Denmark in the subsequent Peace of Lübeck,[29] the situation further deteriorated when the presence of Imperial Catholic troops on the Baltic and the Emperor's "Edict of Restitution" brought King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden into the conflict.[26] Wallenstein attempted to aid the forces of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth under Hetman Stanisław Koniecpolski, which were fighting Sweden in 1629. However, Wallenstein failed to engage any major Swedish forces and this significantly affected the outcome of the conflict.[30]

Over the course of the war Wallenstein's ambitions and the abuses of his forces had earned him a host of enemies, both Catholic and Protestant, princes and non-princes alike. Ferdinand suspected Wallenstein of planning a coup to take control of the Holy Roman Empire. The Emperor's advisors advocated dismissing him, and in September 1630 envoys were sent to Wallenstein to announce his dismissal.[22] The decision was taken at Regensburg on 13 August 1630 on the following day Wallenstein's financier De Witte committed suicide (having accrued a mountain of debt financing Wallenstein).[11]

Wallenstein gave over his army to General Tilly and retired to Jičín, the capital of his Duchy of Friedland. There he lived in an atmosphere of "mysterious magnificence".[31]

However, circumstances forced Ferdinand to recall Wallenstein into the field.[22] The successes of Gustavus Adolphus over General Tilly at the Battle of Breitenfeld and the Lech (1632), where Tilly was killed, and his advance to Munich and occupation of Bohemia, required a vigorous response.[31] It was during this time that Wallenstein had taken inspiration from the reforms of Gustavus Adolphus, instituting harsh discipline by providing rewards for bravery and punishment for disorder, thievery, and cowardice[32] and with this in mind Wallenstein raised a fresh army within a few weeks and took to the field. He drove the Saxon army from Bohemia and then advanced against Gustavus Adolphus, whom he opposed near Nuremberg and, after the Battle of the Alte Veste, dislodged. In November the great Battle of Lützen was fought, in which Wallenstein was forced to retreat but, in the confused melee, Gustavus Adolphus was killed. Wallenstein withdrew to winter quarters in Bohemia.[31]

In the campaigning of 1633, Wallenstein's apparent unwillingness to attack the enemy caused much concern in Vienna and in Spain. At this time the dimensions of the war had grown more European, and Wallenstein had begun preparing to desert the Emperor. He expressed anger at Ferdinand's refusal to revoke the Edict of Restitution. Historic records tell little about his secret negotiations but some sources indicated he was preparing to force a "just peace" on the Emperor "in the interests of united Germany". With this apparent "plan" he entered into negotiations with Saxony, Brandenburg, Sweden, and France. Apparently the Habsburgs' enemies tried to draw him to their side. In any case, he gained little support. Anxious to make his power felt, he resumed the offensive against the Swedes and Saxons, winning his last victory at Steinau on the Oder in October. He then resumed negotiations.[33]

Assassination

In December Wallenstein retired with his army to Bohemia, around Pilsen (now Plzeň). Vienna soon definitely convinced itself of his treachery, a secret court found him guilty, and the Emperor looked seriously for a means of getting rid of him (a successor in command, the later emperor Ferdinand III, was already waiting). Wallenstein was aware of the plan to replace him, but felt confident that when the army came to decide between him and the Emperor the decision would be in his favour.[31]

On 24 January 1634 the Emperor signed a secret patent (shown only to certain officers of Wallenstein's army) removing him from his command. Finally an open patent charging Wallenstein with high treason was signed on 18 February and published in Prague.[22]

In the patent, Ferdinand II ordered to have Wallenstein brought under arrest to Vienna, dead or alive.[34] Losing the support of his army, Wallenstein now realized the extent of his peril, and on 23 February with a company of some hundred men, he went from Plzeň to Eger/Cheb, hoping to meet the Swedes under Prince Bernhard.[35]

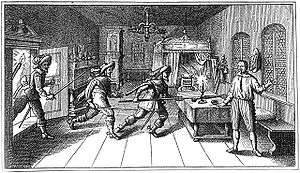

After his arrival at Cheb, however, certain senior Scottish and Irish officers in his force assassinated him on the night of February 25.[31] To carry out the assassination, a regiment of dragoons under the command of an Irish colonel, Walter Butler[36] and the Scots colonels Walter Leslie and John Gordon[37] first fell upon Wallenstein's trusted officers Adam Trczka, Vilém Kinský, Christian Illov and Henry Neumann while the latter attended a feast at Cheb Castle (which had come under the command of Gordon himself), and massacred them. Trczka alone managed to fight his way out into the courtyard, only to be shot down by a group of musketeers.[28]

A few hours later, an Irish captain, Walter Devereux, together with a few companions, broke into the burgomaster's house at the main square where Wallenstein had his lodgings (again courtesy of Gordon), and kicked open the bedroom door. Devereux then ran his halberd through the unarmed Wallenstein, who, roused from sleep, is said to have asked in vain for quarter. The Holy Roman Emperor had given free rein to the parties he knew wished "to bring in Wallenstein, alive or dead". After the assassination, he rewarded them.[38]

Wallenstein was buried at Jičín. In 1785, his remains were moved to Mnichovo Hradiště.

Legacy

The Czech National Museum produced a large exhibition about Wallenstein at the Wallenstein Palace in Prague (current seat of Senate) from 15 November 2007 to 15 February 2008. He is also the subject of Calderón de la Barca's play El prodigio de alemania[39] and Schiller's play trilogy Wallenstein.

Wallenstein is a main figure in Alfred Döblin's eponymous novel.

Composer Bedřich Smetana honored Wallenstein in his 1859 symphonic poem Wallenstein's Camp, which was originally intended as an overture to a play by Schiller.[40]

Josef Rheinberger composed a symphonic tone painting Wallenstein in 1866. The work in four movements is also called a symphony. It was premiered in Munich on 26 November 1866.

Composer Vincent d'Indy honored Wallenstein in his 1871 symphonic triptych Wallenstein.

Wallenstein is examined by economist Arthur Salz in his book Wallenstein als Merkantilist (Wallenstein as Mercantilist).[41]

German folk rock band dArtagnan released the song "Wallenstein" in 2019.[42]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Albrecht von Wallenstein[43][44] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- "In Wallenstein were embodied the fateful forces of his time. He belonged to the men of the Renaissance and the world of the Baroque, but also he stood above these categories as an exceptional individual. He went beyond Czech or German nationality, beyond Catholic or Protestant denominations. [...] He was a Bohemian and a prince of the German Empire."[1]

- Many texts, especially English-language books of the 18th and 19th centuries, name him (incorrectly) as Walstein (no 'd').

References

- Rabb, T. (1964). The Thirty Years' War: Problems of Motive, Extent, and Effect. Boston: Univ. of Am. Press. p. 123.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mortimer, G. (2010). Wallenstein: The Enigma of the Thirty Years War. p. 69. doi:10.1057/9780230282100. ISBN 978-0-230-27212-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Wallenstein, Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von, Herzog (duke) von Friedland, Herzog von Mecklenburg, Fürst (prince) Von Sagen", Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2010

- Coxe, W. (1852). History of the House of Austria vol. II (3rd ed.). London: H.G. Bohn. p. 203.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steinberg 1998.

- Schiller, F. (1911). Max Winkler (ed.). Schiller's Wallenstein. Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rebitsch, R. (2010). Wallenstein: Biografie eines Machtmenschen (in German). Vienna: Böhlau. p. 22. ISBN 978-3-205-78583-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rebitsch 2010, pp. 22–23.

- Rebitsch 2010, p. 23.

- Mann, G.; Bliggenstorfer, Ruedi (1973). Wallenstein. Fischer. p. 128.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallenstein his life narrated by Golo Mann.

- Rebitsch 2010, p. 24.

- Ripley, G.; Dana, C., eds. (1863). New American Cyclopædia. 16. New York: D. Appleton & Company. p. 186. Archived.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ripley & Dana 1863, p. 186.

- Marek, Miroslav. "Genealogy site". euweb.cz.

- Marek, Miroslav. "Waldstein". Genealogy.EU.

- Rebitsch 2010, pp. 24–26.

- Rebitsch 2010, p. 26.

- Maierhofer, Waltraud (2005). Bilder des Weiblichen in Erzähltexten über den Dreissigjährigen Krieg. Köln Weimar: Böhlau. pp. 39, 418. ISBN 3412104051.

- Rebitsch 2010, p. 27.

- Di Bert, Marino Vicende storiche gradiscane, Società Filologica Friulana, Udine, pp. 65–104.

- Schiller, J. Friedrich Von. (1980) Robbers and Wallenstein, Penguin Classics, pp. 12–3. ISBN 0-14-044368-1.

- Mann, Golo, Wallenstein

- JP Cooper, "The New Cambridge Modern History" The Thirty Years’ War 1st ed. (New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. 1970), 323.

- Eggenberger, David. (1985) An Encyclopedia of Battles, Courier Dover Publications. p. 161. ISBN 0-486-24913-1.

- Fuller, J. F. C. (1987) A Military History of the Western World, Da Capo Press. pp. 46–47; ISBN 0-306-80305-4.

- Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2005) Western Civilization, Thomson Wadsworth, p. 414; ISBN 0-534-64604-2.

- Wedgwood, C.V. (1961) The Thirty Years War, Anchor Books, pp. 219–20.

- Lockhart, Paul Douglas (2007). Denmark, 1513–1660: the rise and decline of a Renaissance monarchy. Oxford University Press. pp. 166–71. ISBN 0-19-927121-6. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Dahlquist, Germund Wilhelm & Carl Von Clausewitz. (2003) Principles of War, Courier Dover Publications, p. 81. ISBN 0-486-42799-4.

- Ingrao, Charles W. (2000) The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618–1815, Cambridge University Press, pp. 45–46; ISBN 0-521-78505-7.

- Mears, John A. (June 1988). "The Thirty Years' War, the "General Crisis," and the Origins of a Standing Professional Army in the Habsburg Monarchy". Central European History. 21 (2): 134. JSTOR 4546115.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 281.

- Lunde, Henrik (2014). A Warrior Dynasty. Casemate. p. 169.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 282.

- Projekt Runeberg: Walter Butler, runeberg.org; accessed April 17, 2017.

- Mitchell, James (1887). Life of Wallenstain,Duke of Friendland. London, UK: James Fraser. p. 323.

- The Encyclopedia of World History (6th edition)

- Muratta Bunsen, Eduardo (2017). "El Wallenstein español. Consideraciones sobre el ethos militar, con el ejemplo de El Prodigio de Alemania". In Tietz, Manfred. Figuras del bien y del mal. La construcción cultural de la masculinidad y de la feminidad en el teatro calderoniano. Madrid: Academia del Hispanismo, pp. 451–80; ISBN 978-84-16187-60-7

- Liner notes to Deutsche Grammophon recording 437254-2

- Salz, Arthur (1909). Wallenstein als Merkantilist.

- https://www.dartagnan.de/home/

- Genealogie České Šlechty, patricus.info; accessed 24 June 2017.

- Marek, Miroslav. "Genealogy". Genealogy.EU.

Sources

- Cristini, Luca. 1618–1648 la guerra dei 30 anni. Volume 1 da 1618 al 1632 2007 ISBN 978-88-903010-1-8 and Volume 2 da 1632 al 1648 2007 ISBN 978-88-903010-2-5

- Mann, Golo. Wallenstein, his life narrated, 1976, Holt, Rinehart and Winston (ISBN 0030918847).

- Steinberg, S.H. (20 July 1998). "Albrecht von Wallenstein". Encyclopædia Britannica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albrecht von Waldstein. |

- Fortune City. "Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Wallenstein". Fortune City.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Ripley, G. & Dana, C., eds. (1879). American Cyclopædia. 16 (2nd ed.). New York: D. Appleton & Company. pp. 435–7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Thirty-Years-War

- An Exhibition at Prague, Czech Republic, Europe – Dedicated to Albrecht von Wallenstein

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- "Wallenstein: Generalissimo" from Military Heritage magazine

- Albrecht von Wallenstein – In spite of envy