Wallace Line

The Wallace Line or Wallace's Line is a faunal boundary line drawn in 1859 by the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace and named by English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley that separates the biogeographical realms of Asia and Wallacea, a transitional zone between Asia and Australia. West of the line are found organisms related to Asiatic species; to the east, a mixture of species of Asian and Australian origin is present. Wallace noticed this clear division during his travels through the East Indies in the 19th century.

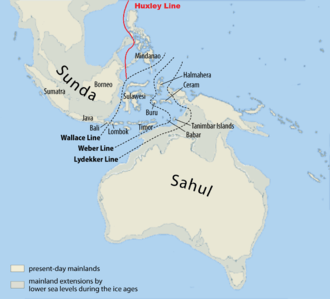

The line runs through Indonesia, between Borneo and Sulawesi (Celebes), and through the Lombok Strait between Bali and Lombok. The distance between Bali and Lombok is small, about 35 kilometres (22 mi). The distributions of many bird species observe the line, since many birds do not cross even the shortest stretches of open ocean water. Some bats have distributions that cross the line, but larger terrestrial mammals are generally limited to one side or the other; exceptions include macaques, pigs and tarsiers on Sulawesi. Other groups of plants and animals show differing patterns, but the overall pattern is striking and reasonably consistent. Flora do not follow the Wallace Line to the same extent as fauna.[1] One genus of plants which does not cross the Line is the Australasian genus Eucalyptus.

Historical context

Antonio Pigafetta had recorded the biological contrasts between the Philippines and the Maluku Islands (Spice Islands) (on opposite sides of the line) in 1521 during the continuation of the voyage of Ferdinand Magellan, after Magellan had been killed on Mactan. Moreover, as noted by Wallace himself, the observations in faunal differences between the two regions had already been made earlier by English navigator George Windsor Earl. In Wallace's pamphlet On the Physical Geography of South-Eastern Asia and Australia, published in 1845, he described how shallow seas connected islands on the west (Sumatra, Java, etc.) with the Asian continent and with similar wildlife, and islands on the east such as New Guinea were connected to Australia and were characterised by the presence of marsupials. Wallace used his extensive travel in the region to propose a line to the east of Bali since "all the islands eastward of Borneo and Java formed part of an Australian or Pacific Continent, from which they were separated."[2] The name 'Wallace's Line' was first used by Thomas Huxley in an 1868 paper to the Zoological Society of London, but showed the line to the west of the Philippines.[3][4] Wallace's studies in Indonesia demonstrated the emerging theory of evolution, at about the same time as Joseph Dalton Hooker and Asa Gray published essays also supporting Darwin's hypothesis.[5]

Biogeography

Understanding of the biogeography of the region centers on the relationship of ancient sea levels to the continental shelves. Wallace's Line is visible geographically when the continental shelf contours are examined; it can be seen as a deep-water channel that marks the southeastern edge of the Sunda Shelf which links Borneo, Bali, Java, and Sumatra underwater to the mainland of southeastern Asia. Australia is likewise connected by the Sahul Shelf to New Guinea. The biogeographic boundary known as Lydekker's Line, which separates the eastern edge of Wallacea from the Australian region, has a similar origin to the Wallace line.

During ice age glacial advances, when the ocean levels were up to 120 metres (390 ft) lower, both Asia and Australia were united with what are now islands on their respective continental shelves as continuous land masses, but the deep water between those two large continental shelf areas was, for over 50 million years, a barrier that kept the flora and fauna of Australia separated from those of Asia. Wallacea consists of islands that were not recently connected by dry land to either of the continental land masses, and thus were populated by organisms capable of crossing the straits between islands. "Weber's Line" runs through this transitional area (to the east of centre), at the tipping point between dominance by species of Asian against those of Australian origin.[6]

It can reasonably be concluded it was an ocean barrier preventing species migration because the physical aspects of the separated islands are very similar.[7] Species found only on the Asian side include tigers and rhinoceroses, while marsupials and monotremes are only found on the eastern side of the Line.[8]

See also

- Australia (continent) – continental mainland on the Australian Plate

- Australasian realm

- Wallacea – Biogeographical designation for a group of mainly Indonesian islands separated by deep-water straits from the Asian and Australian continental shelves

Citation and notes

- Van Welzen, P. C.; Parnell, J. A. N.; Slik, J. W. F. (2011). "Wallace's Line and plant distributions: Two or three phytogeographical areas and where to group Java?". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 103 (3): 531–545. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01647.x.

- Wallace 1863, p. 231.

- Huxley, T. H. (1868). "On the Classification and Distribution of the Alectoromorphae and Heteromorphae". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 294–319. Retrieved Apr 25, 2015.

- Camerini, Jane R. (1993). "Evolution, Biogeography, and Maps". Isis. 84: 700–727. doi:10.1086/356637. PMID 8307726.

- Bowler, Peter J. (1989). Evolution: The History of an Idea. University of California Press. p. 193. ISBN 0520063864. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Mayr, E. (1944), "Wallace's Line in the Light of Recent Zoogeographic Studies", The Quarterly Review of Biology, 19 (1): 1–14, doi:10.1086/394684, JSTOR 2808563

- Newton, Alfred (1874). Zoology. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 51. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Riley, Laura; William Riley (2005). Nature's Strongholds: The World's Great Wildlife Reserves. Princeton University Press. p. 602. ISBN 0691122199. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

References

- Wallace, Alfred Russel (1863). "On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago". Royal Geographical Society. 7: 205–212.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) with the original paper

Further reading

- van Oosterzee, Penny (1997). Where Worlds Collide: the Wallace Line.

- Dawkins, Richard (2004). The Ancestor's Tale. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-7538-1996-1. Chapter 14 - Marsupials.

- Abdullah, M. T. (2003). Biogeography and variation of Cynopterus brachyotis in Southeast Asia. PhD thesis. The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Australia.

- Hall, L. S., Gordon G. Grigg, Craig Moritz, Besar Ketol, Isa Sait, Wahab Marni and M. T. Abdullah (2004). "Biogeography of fruit bats in Southeast Asia". Sarawak Museum Journal LX(81):191-284.

- Wilson D. E., D. M. Reeder (2005). Mammal species of the world. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

External links

- Too Many Lines; The Limits of the Oriental and Australian Zoogeographic Regions George Gaylord Simpson, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 121, No. 2 (Apr. 29, 1977), pp. 107–120

- Wallacea Research Group

- Map of Wallace's, Weber's and Lydekker's lines

- Pleistocene Sea Level Maps

- Wallacea - a transition zone from Asia to Australia, specially rich in marine life and on land