Forceps

Forceps (plural forceps[1][2] or considered a plural noun without a singular, often a pair of forceps;[3][4] the Latin plural forcipes is no longer recorded in most dictionaries)[1][2][3][4] are a handheld, hinged instrument used for grasping and holding objects. Forceps are used when fingers are too large to grasp small objects or when many objects need to be held at one time while the hands are used to perform a task. The term "forceps" is used almost exclusively within the medical field. Outside medicine, people usually refer to forceps as tweezers, tongs, pliers, clips or clamps.

Mechanically, forceps employ the principle of the lever to grasp and apply pressure.

Depending on their function, basic surgical forceps can be categorized into the following groups:

- Non-disposable forceps. They should withstand various kinds of physical and chemical effects of body fluids, secretions, cleaning agents, and sterilization methods.

- Disposable forceps. They are usually made of lower-quality materials or plastics which are disposed after use.

Surgical forceps are commonly made of high-grade carbon steel, which ensures they can withstand repeated sterilization in high-temperature autoclaves. Some are made of other high-quality stainless steel, chromium and vanadium alloys to ensure durability of edges and freedom from rust. Lower-quality steel is used in forceps made for other uses. Some disposable forceps are made of plastic. The invention of surgical forceps is attributed to Stephen Hales.[5]

There are two basic types of forceps: non-locking (often called "thumb forceps" or "pick-ups") and locking, though these two types come in dozens of specialized forms for various uses. Non-locking forceps also come in two basic forms: hinged at one end, away from the grasping end (colloquially such forceps are called tweezers) and hinged in the middle, rather like scissors. Locking forceps are almost always hinged in the middle, though some forms place the hinge very close to the grasping end. Locking forceps use various means to lock the grasping surfaces in a closed position to facilitate manipulation or to independently clamp, grasp or hold an object.

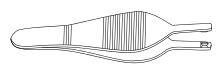

Thumb forceps

Thumb forceps are commonly held between the thumb and two or three fingers of one hand, with the top end resting on the first dorsal interosseous muscle at the base of the thumb and index finger. Spring tension at one end holds the grasping ends apart until pressure is applied. This allows one to quickly and easily grasp small objects or tissue to move and release it or to grasp and hold tissue with easily variable pressure. Thumb forceps are used to hold tissue in place when applying sutures, to gently move tissues out of the way during exploratory surgery and to move dressings or draping without using the hands or fingers.

Thumb forceps can have smooth tips, cross-hatched tips or serrated tips (often called "mouse's teeth"). Common arrangements of teeth are 1×2 (two teeth on one side meshing with a single tooth on the other), 7×7 and 9×9. Serrated forceps are used on tissue; counter-intuitively, teeth will damage tissue less than a smooth surface because one can grasp with less overall pressure. Smooth or cross-hatched forceps are used to move dressings, remove sutures and similar tasks.

Locking forceps

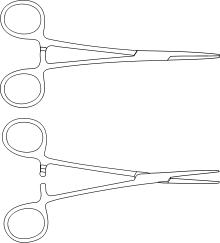

Locking forceps, sometimes called clamps, are used to grasp and hold objects or tissue. When they are used to compress an artery to forestall bleeding, they are called hemostats. Another form of locking forceps is the needle holder, used to guide a suturing needle through tissue. Many locking forceps use finger loops to facilitate handling (see illustration, below, of Kelly forceps). The finger loops are usually grasped by the thumb and middle or ring fingers, while the index finger helps guide the instrument.

The most common locking mechanism is a series of interlocking teeth located near the finger loops. As the forceps are closed, the teeth engage and keep the instrument's grasping surfaces from separating. A simple shift of the fingers is all that is needed to disengage the teeth and allow the grasping ends to move apart. Forceps are also used for surgery.

Kelly forceps

Kelly forceps are a type of hemostat usually made of stainless steel. They resemble a pair of scissors with the blade replaced by a blunted grip. They also feature a locking mechanism to allow them to act as clamps. Kelly forceps may be floor-grade (regular use) and as such not used for surgery. They may also be sterilized and used in operations, in both human and veterinary medicine. They may be either curved or straight. In surgery, they may be used for occluding blood vessels, manipulating tissues, or for assorted other purposes. They are named for Howard Atwood Kelly, M.D., first professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. The "mosquito" variant of the tool is more delicate and has smaller, finer tips. Other varieties with similar, if more specialized, uses are Allis clamps, Babcocks, Kochers, Carmalts, and tonsils; all but the last bear the names of the surgeons who designed them.

Other medical forceps

Other types of forceps include:

- Magill forceps, which are angled forceps used to guide a tracheal tube into the larynx or a nasogastric tube into the esophagus under direct vision.[6] They are also used to remove foreign bodies.[6]

- Alligator forceps

- Anesthesia forceps

- Artery forceps

- Atraumatic forceps

- Biopsy forceps

- Bone-cutting forceps

- Bone-reduction forceps

- Bone-holding forceps

- Bulldog forceps

- Catheter forceps

- Cilia forceps

- Curettes forceps

- Cushing forceps

- Debakey forceps

- Dermal forceps & nippers

- Dressing forceps

- Ear forceps

- Eye forceps

- Gallbladder forceps

- Gerald forceps

- Hemostatic forceps

- Hysterectomy forceps

- Intestinal forceps

- Microsurgery forceps

- Nasal forceps

- Obstetrical forceps

- Postmortem forceps

- Splinter forceps

- Sponge forceps

- Spreading forceps

- Sterilizer forceps

- Suture sundries forceps

- Tenaculum forceps

- Thoracic forceps

- Thoracic surgical forceps

- Thumb forceps

- Tissue forceps

- Tongue forceps

- Tooth extracting forceps

- Tubing forceps

- Uterine forceps

- Vulsellum forceps

- Wire cutting forceps

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Forceps. |

References

- Company, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing. "The American Heritage Dictionary entry: forceps". www.ahdictionary.com. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- "Definition of FORCEPS". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- "forceps Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- "forceps - Definition of forceps in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries - English. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Scientific American inventions and discoveries By Rodney P. Carlisle.

- Magill forceps in Farlex medical dictionary, citing Mosby's Medical Dictionary, 8th edition.