Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich

Vladimir Dmitriyevich Bonch-Bruyevich (Russian: Владимир Дмитриевич Бонч-Бруевич; sometimes spelled Bonch-Bruevich; in Polish Boncz-Brujewicz; 28 June [O.S. 16 June] 1873 – 14 July 1955) was a Soviet politician, revolutionary, historian, writer and Old Bolshevik (from 1895). He was Vladimir Lenin's personal secretary.[1] He was a brother of Mikhail Dmitriyevich Bonch-Bruyevich.

Vladimir Dmitriyevich Bonch-Bruyevich | |

|---|---|

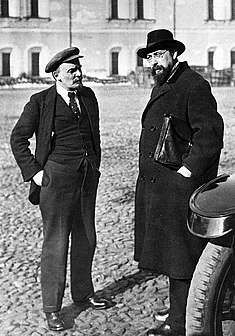

Vladimir Dmitriyevich Bonch-Bruyevich in 1919 | |

| Born | Vladimir Dmitriyevich Bonch-Bruyevich 28 June 1873 |

| Died | 14 July 1955 (aged 82) Moscow, Russian SFSR |

| Occupation | Revolutionary, politician, writer, researcher, historian |

Early life

Vladimir Dmitriyevich Bonch-Bruyevich was born in Moscow to a land surveyor family who came from the Mogilev province and belonged to the nobility of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. At the age of ten, he was sent to the Moscow Institute of Surveying and graduated from the school of land surveying. In 1889, he was arrested for taking part in a student demonstration, and banished to Kursk[2].He returned to Moscow in 1892 and entered the "Moscow Workers' Union" and distributed illegal literature. From 1895 he was active in the social-democratic circles. In 1896 he emigrated to Switzerland and organized shipments of Russian revolutionary literature and printing equipment and became an active member of Iskra.

Researching dissenters and supporting Doukhobors

One of Bonch-Bruyevich's research interests were Russia's dissenting religious minorities ("sects"), which were usually persecuted to various extent by both the established Orthodox Church and the Tsarist government. He believed that Baptists and Flagellants were "transmission points" for revolutionary propaganda.[3] During the 1917 revolutions, he is reputed to have played a crucial in neutralising the Cossack garrison in the capital, Petrograd, through his contacts in the New Israel and Old Israel sects.[4] He also met Grigori Rasputin, but judged that he was an Orthodox christian, not sectarian.[5]

In the late 1890s, he collaborated with Vladimir Chertkov and Leo Tolstoy,[6] in particular in the arrangement of the Doukhobors' emigration to Canada in 1899. Bonch-Bruyevich sailed with the Doukhobors, and spent a year with them in Canada. During that time, he was able to record much of their orally transmitted tradition, in particular the Doukhobor "psalms" (hymns). He published them later (1909) as "The Doukhobor Book of Life" (Russian: «Животная книга духоборцев», Zhivotnaya Kniga Dukhobortsev).[7][8][9]

Political activism

When the RSDLP split in 1903 between the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, and the Mensheviks, Bonch-Bruyevich was among the original Bolsheviks. He helped bring out the RSDLP newspaper Iskra while it was still under Lenin's control, and backed Lenin during 1904, when it appeared he might be losing control of the Bolsheviks to conciliators who wanted to heal the split. In Dember 1904, he helped organise Vpered, the first Bolshevik newspaper. According to Lenin's widow "Bonch-Bruyeich was in charge of the business side. He permanently beamed, concocted divers grandiose plans, and was always dashing around on printing-press matters."[10] He also helped set up and run the party archive.

Bonch-Bruyevich returned to Russia early in 1905, and for a time worked illegally for the Bolsheviks in St Petersburg, organising the underground storage of weapons. After the 1905 revolution, he was able to operate legally. In 1906, he organised the Bolsheviks' weekly newspaper Наша мысль (Nasha mysl - Our Beliefs), the journal Вестник жизни (Vestnik zhizni - Herald of Life) and several other publications. From 1907, he headed the Bolshevik publishing house, Жизнь и знание (Zhizn i znanie - Life and Knowledge).[2] From 1912 he was a member of the editorial board of the newspaper Pravda. During this time he was repeatedly arrested, but did not serve a long prison sentence.

On the outbreak of the February Revolution, in 1917, Bonch-Bruyevich founded the newspaper Izvestya, and used it in April as a vehicle to defend Lenin's decision to return to Russia through Germany, despite the two countries being at war. He was dismissed from the staff by the Menshevik-controlled Petrograd soviet in May for using it to disseminate Bolshevik propaganda. During June and July 1917, Bolshevik party meetings were held at his dacha, to avoid the attention of the police. In August, the head of the provisional government, Alexander Kerensky ordered his arrest, and he went into hiding. During the October Revolution, he was in charge of protecting the Bolshevik party headquarters in the Smolny Institute, in Petrograd.[11]

Bonch-Bruyevich was head of administration for the Council of People's Commissars (equivalent to head of Lenin's private office) from November 1917 to October 1920. Between December 1917 and March 1918 he was the chairman of the Committee against the pogroms and in February – March 1918 a member of the Committee for the Revolutionary Defense of Petrograd. From 1918 he was Deputy Chairman of the Board of Medical Colleges. In 1919 he was Chairman of the Committee for the construction of sanitary checkpoints at railway stations in Moscow and the Special Committee for Rehabilitation of water supply and sanitation in Moscow. Between 1918–1919 he was the head of the publishing house of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) "Kommunist."

%2C_1918.jpg)

Bonch-Bruevich took an active part in the nationalization of the banks in the preparation of the Soviet government moving to Moscow in March 1918. In 1918 as Managing Director of the Council of the People's Commissars, he endorsed setting in motion the Red Terror.

In 1918 he was elected a member of the Socialist Academy of Social Sciences. After Lenin's death, he did research and authored works on the history of the revolutionary movement in Russia, the history of religion and atheism, sectarianism, ethnography and literature. In the Soviet Union, Bonch-Bruyevich was best known as the author of a canonical Soviet book about Vladimir Lenin, whom Bonch-Bruyevich served as secretary in the years immediately following the Bolshevik revolution in 1917.[12]

Following Lenin's death, Bonch-Bruevich was one of the key people involved in organising the funeral. He personally opposed the mummification of Lenin's body.[13]

Between 1920 and 1929 he was the organizer and leader of a farm that supplied its products mostly to the leaders of the Communist party and the government.

Beginning in 1933, he was the director of the State Literary Museum in Moscow. Between 1946 and 1953 he was the director of the Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism, Academy of Sciences of the USSR in Leningrad.

Bonch-Bruyevich died on 14 July 1955. He was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

Bonch-Bruyevich's daughter, Yelena, married Leopold Averbakh. After her husband's arrest, she was sentenced to seven years in the labour camps.

Awards

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vladimir Dmitriyevich Bonch-Bruyevich. |

- The Russian Civil War by Evan Mawdsley, Birlinn, 2008

- Shmidt, O.Yu. (chief editor), Bukharin N.I. et al (eds) (1927). Большая советская энциклопедия volume 7. Moscow. p. 125.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Slezkine, Yuri (2017). The House of Government, a Saga of the Russian Revolution. Princeton: Princeton U.P. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-69119-272-7.

- Katkov, George (1969). Russia 1917: the February Revolution. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-000-632068-5.

- Shlyakhov, Andrei (5 September 2017). Распутин. Три демона последнего святого. ISBN 978-5457173255. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- O.A. Golinenko (О.А. ГОЛИНЕНКО) "Leo Tolstoy's questions to a Doukhobor" (ВОПРОСЫ Л.Н. ТОЛСТОГО ДУХОБОРУ) (in Russian)

- (in Russian)

- Н. В. Сомин. «Духоборы» (in Russian)

- В.Д. Бонч-Бруевич, Животная книга духоборцев, Санкт-Петербург, 1909. (The Doukhobor Book of Life — Complete Russian book at www.archive.org) (in Russian)

- Krupskaya, Nadezhda (1970). Memories of Lenin. Panther. p. 112.

- "Бонч-Бруевич Владимир Дмитриевич". ldn-knigi.lib.ru. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- "The Cheka: Lenin's Political Police", NY, Oxford University Press, 1981, p. 197

- Tumarkin, Nina (1981). "Religion, Bolshevism, and the Origins of the Lenin Cult". Russian Review. 40 (1): 35–46. doi:10.2307/128733. JSTOR 128733.

External links

- The Committee to combat pogroms (in Russian)