Vinyl acetate

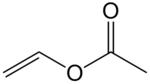

Vinyl acetate is an organic compound with the formula CH3CO2CH=CH2. This colorless liquid is the precursor to polyvinyl acetate, an important industrial polymer.[3]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Ethenyl acetate | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

Ethenyl ethanoate | |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.224 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | C011566 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H6O2 | |

| Molar mass | 86.090 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid |

| Odor | Sweet, pleasant, fruity; may be sharp and irritating[1] |

| Density | 0.934 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | −93.5 °C (−136.3 °F; 179.7 K) |

| Boiling point | 72.7 °C (162.9 °F; 345.8 K) |

| -46.4·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 0347 |

| R-phrases (outdated) | R11 |

| S-phrases (outdated) | S16, S23, S29, S33 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | −8 °C (18 °F; 265 K) |

| 427 °C (801 °F; 700 K) | |

| Explosive limits | 2.6–13.40% |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

none[2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Production

The worldwide production capacity of vinyl acetate was estimated at 6,969,000 tonnes/year in 2007, with most capacity concentrated in the United States (1,585,000 all in Texas), China (1,261,000), Japan (725,000) and Taiwan (650,000).[4] The average list price for 2008 was $1600/tonne. Celanese is the largest producer (ca 25% of the worldwide capacity), while other significant producers include China Petrochemical Corporation (7%), Chang Chun Group (6%), and LyondellBasell (5%).[4]

It is a key ingredient in furniture glue.[5]

Preparation

Vinyl acetate is the acetate ester of vinyl alcohol. Since vinyl alcohol is highly unstable (with respect to acetaldehyde), the preparation of vinyl acetate is more complex than the synthesis of other acetate esters.

The major industrial route involves the reaction of ethylene and acetic acid with oxygen in the presence of a palladium catalyst.[6]

The main side reaction is the combustion of organic precursors.

Mechanism

Isotope labeling and kinetics experiments suggest that the mechanism involves PdCH2CH2OAc-containing intermediates. Beta-hydride elimination would generate vinyl acetate and a palladium hydride, which would be oxidized to give hydroxide.[7]

Alternative routes

Vinyl acetate was once prepared by hydroesterification. This method involves the gas-phase addition of acetic acid to acetylene in the presence of metal catalysts. By this route, using mercury(II) catalysts, vinyl acetate was first prepared by Fritz Klatte in 1912.[3] Another route to vinyl acetate involves thermal decomposition of ethylidene diacetate:

Polymerization

It can be polymerized to give polyvinyl acetate (PVA). With other monomers it can be used to prepare various copolymers such as ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA), vinyl acetate-acrylic acid (VA/AA), polyvinyl chloride acetate (PVCA), and polyvinylpyrrolidone (Vp/Va Copolymer, used in hair gels).[8] Due to the instability of the radical, attempts to control the polymerization via most 'living/controlled' radical processes have proved problematic. However, RAFT (or more specifically MADIX) polymerization offers a convenient method of controlling the synthesis of PVA by the addition of a xanthate or a dithiocarbamate chain transfer agent.

Other reactions

Vinyl acetate undergoes many of the reactions anticipated for an alkene and an ester. Bromine adds to give the dibromide. Hydrogen halides add to give 1-haloethyl acetates, which cannot be generated by other methods because of the non-availability of the corresponding halo-alcohols. Acetic acid adds in the presence of palladium catalysts to give ethylidene diacetate, CH3CH(OAc)2. It undergoes transesterification with a variety of carboxylic acids.[9] The alkene also undergoes Diels-Alder and 2+2 cycloadditions.

Vinyl acetate undergoes transesterification, giving access to vinyl ethers:[10][11]

- ROH + CH2=CHOAc → ROCH=CH2 + HOAc

Toxicity evaluation

Tests suggest that vinyl acetate is of low toxicity. For rats (oral) LD50 is 2920 mg/kg.[3]

On January 31, 2009, the Government of Canada's final assessment concluded that exposure to vinyl acetate is not harmful to human health.[12] This decision under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA) was based on new information received during the public comment period, as well as more recent information from the risk assessment conducted by the European Union.

It is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the U.S. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002), and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities which produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[13]

See also

References

- "Public Health Statement for Vinyl Acetate". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Centers for Disease Control.

It has a sweet, pleasant, fruity smell, but the odor may be sharp and irritating to some people.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0656". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- G. Roscher (2007). "Vinyl Esters". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a27_419. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- H. Chinn (September 2008). "CEH Marketing Research Report: Vinyl Acetate". Chemical Economics Handbook. SRI consulting. Retrieved July 2011. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Karl Shmavonian (2012-10-24). "Madhukar Parekh's Pidilite Industries Earns His Family $1.36 Billion". Forbes.com. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

though Pidilite has had to contend with the rising price of vinyl acetate monomer, its key raw material

- Y.-F. Han; D. Kumar; C. Sivadinarayana & D.W. Goodman (2004). "Kinetics of ethylene combustion in the synthesis of vinyl acetate over a Pd/SiO2 catalyst" (PDF). Journal of Catalysis. 224: 60–68. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2004.02.028.

- Stacchiola, D.; Calaza, F.; Burkholder, L.; Schwabacher Alan, W.; Neurock, M.; Tysoe Wilfred, T. (2005). "Elucidation of the Reaction Mechanism for the Palladium‐Catalyzed Synthesis of Vinyl Acetate". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 44 (29): 4572–4574. doi:10.1002/anie.200500782. PMID 15988776.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "VP/VA Copolymer". Personal Care Products Council. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- D. Swern & E. F. Jordan, Jr. (1963). "Vinyl Laurate and Other Vinyl Esters" (PDF). Organic Syntheses, Collected Volume 4: 977. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- Tomotaka Hirabayashi, Satoshi Sakaguchi, Yasutaka Ishii (2005). "Iridium-catalyzed Synthesis of Vinyl Ethers from Alcohols and Vinyl Acetate". Org. Synth. 82: 55. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.082.0055.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Yasushi Obora, Yasutaka Ishii (2012). "Discussion Addendum: Iridium-catalyzed Synthesis of Vinyl Ethers from Alcohols and Vinyl Acetate". Org. Synth. 89: 307. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.089.0307.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- http://www.ec.gc.ca/ese-ees/59EC93F6-2C5D-42B4-BB09-EB198C44788D/batch2_108-05-4_pc_en.pdf

- "40 C.F.R: Appendix A to Part 355—The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities" (PDF). Code of Federal Regulations (December 2017 ed.). Government Printing Office. title 40, vol 30, part 355, app A (EPA): 474. December 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2018 – via US GPO.