Vietnam arquebus

Vietnam arquebus refer to several type of gunpowder firearms produced historically in Vietnam. This page also include Vietnamese muskets - since the early definition of musket is "heavy arquebus".[1] The term Vietnam arquebus comes from Chinese word Jiao Chong (交銃, lit. 'Jiaozhi Arquebus'), a generalization of firearms originating from Dai Viet.[2]

History

Dai Viet used to have a relatively early tradition of using gunpowder weapon, perhaps imported from the Ming Dynasty. At the end of the 14th century, king Che Bong Nga of Champa died in battle when he was hit by hand cannon of the Tran army while he was surveying on the Hai Trieu River.[3] Until the Ho dynasty, Ho Nguyen Trung manufactured Than Co Sang cannon.[4] By the time of Lê So, gunpowder weapons began to be widely used in the army. In Thailand, a gun was discovered that was originally believed to have originated in China, but based on the inscriptions on the gun they confirmed its Dai Viet origin. This is most likely a relic of the invasion of the Lanna kingdom (present day Chiang Mai) under Le Thanh Tong in 1479-1484.

By the 16th century, when Europeans came to Dai Viet to trade, Western weapons were purchased by lords to equip their armies and muskets began to be imported into Dai Viet ever since. Tome Pires in his Suma Oriental (1515) mentioned that Cochin China has countless musketeers and small bombards. Pires also mentioned that very much gunpowder is used in war and for amusement.[5]:115 The Dai Viet muskets were not only widely used domestically, but also introduced into the Ming dynasty after the border conflicts between the Mac dynasty and ethnic minority groups in Guangxi and Yunnan.

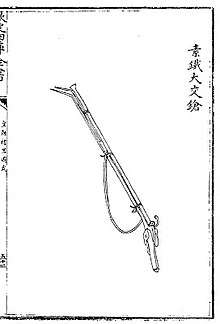

Malay and Trinh Vietnamese soldiers used bamboo covers in their matchlock arquebus barrel and bound them with rattan, to keep them dry when marching in the rain. Vietnamese people also had a smaller piece of bamboo to put over the barrel, to prevent the gun from accumulating dust when it was placed on a weapon rack. The Vietnamese used such arquebus to harass a Spanish armada off shore in the late 16th century with some success.[6] This gun is similar in form to an istinggar, but has longer buttstock.

The Jiaozhi arquebus is not only highly appreciated by the Chinese, but also praised especially by Western observers for its high accuracy in what they saw in the Le-Mac and Trinh-Nguyen wars. The Minh dynasty also rated Dai Viet arquebus as "the best gun in the world", even surpassing the Ottoman gun, the Japanese gun and the European gun. According to Dr. Ly Ba Trong, former head of the history department at Thanh Hoa University:[7]

At the end of the Ming Dynasty, the Annam people developed a matchlock gun with excellent performance, which the Chinese called "Jiao Chong" (meaning Jiaozhi gun). Some people think that this kind of gun is superior to the Western and Japanese "Niao Chong" (鳥銃, 'Bird gun') and "Lu Mi Chong" (魯密銃, 'Rûm arquebus') in terms of power and performance.

Luu Hien Dinh, who lived at the end of the Ming dynasty and early Thanh's, commented:[8]

"Jiaozhi matchlock is the best of the world"

Dai Viet gun can penetrate many layers of iron armor, can kill from 2 to 5 people with one bullet but does not emit loud sound when fired.

In the late 17th century AD, Trinh army used long muskets, with the barrels alone being between 1.2 to 2 meters in length, resulting in heavier weight. They were carried on man's back and fired 124 g shot. To fire it requires a stand, from a piece of wood from 1.83-2.13 m long.[9]

A gun similar to gingal, with wooden stand and swivel is also reported:[10]

"One end of the carriage is supported with 2 legs, or a fork of 3 foot high, the other rests on the ground. The gun is placed on the top, where there is an iron socket for the gun to rest in, and a swivel to turn the muzzle in any way. From the breech of the gun there is a short stock for the man who fires the gun to transverse it withal, and to rest it against his shoulder ..."

Even in the late 18th century, Nguyen musketeers relied on long matchlocks with swivels and three-legged stands.[11]

References

- Arnold, 2001, The Renaissance at War, p. 75-78

- Tiaoyuan, Li (1969). South Vietnamese Notes. Guangju Book Office.

- Tran, Nhung Tuyet (2006). Viêt Nam Borderless Histories. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 75.

- Phạm Trường Giang (2017-07-23). "Dấu vết của 'thần cơ' Hồ Nguyên Trừng". PLO. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- Pires, Tome (1944). The Suma oriental of Tomé Pires : an account of the East, from the Red Sea to Japan, written in Malacca and India in 1512-1515 ; and, the book of Francisco Rodrigues, rutter of a voyage in the Red Sea, nautical rules, almanack and maps, written and drawn in the East before 1515. The Hakluyt Society. ISBN 9784000085052.

- Charney (2004). p. 53.

- Lý Bá Trọng (2019). 火槍與帳簿:早期經濟全球化時代的中國與東亞世界 (in Chinese). 聯經出版事業公司. p. 142. ISBN 978-957-08-5393-3. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

鐵砲,從隼銃(falcon)到寇飛寧(culverin)砲一應俱全。鄭氏軍隊中有一支7,000至8,000人的部隊,裝備有1至1.2米長的重火繩槍。這些士兵都攜帶皮製的彈藥箱,裡頭裝有數份剛好供一次發射所需火藥量的藥包,以便將火藥迅速倒入槍管,因此被認為是裝填最快的火槍手。在明末,安南人開發出了一種性能優良的火繩槍,中國人稱之為「交銃」(意即交趾火銃)。有人認為這種交銃在威力及性能等方面都優越於西方和日本的「鳥銃」及「魯密銃」。

- Lý Bá Trọng (2019). 火槍與帳簿:早期經濟全球化時代的中國與東亞世界 (in Chinese). 聯經出版事業公司. p. 142. ISBN 978-957-08-5393-3. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

明清之際人劉獻廷說:「交善火攻,交槍為天下最。」屈大均則說:「有交槍者,其日爪哇銃者,形如強弩,以繩懸絡肩上,遇敵萬統齊發,貫甲數重。」

- Charney (2004). p. 54.

- Charney (2004). p. 54-55.

- Charney (2004). p. 55.

Further reading

- Charney, Michael (2004). Southeast Asian Warfare, 1300-1900. BRILL. ISBN 9789047406921