Paul Hankar

Paul Hankar (11 December 1859 – 17 January 1901) was a Belgian architect and furniture designer, and an innovator in the Art Nouveau style.

Paul Hankar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 11 December 1859 |

| Died | 17 January 1901 (aged 41) Brussels, Province of Brabant, Belgium |

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings |

|

| Projects |

|

Career

He was born at Frameries, the son of a stonemason. He studied at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, where he met fellow student (and future architect) Victor Horta. Like Horta, he closely studied the techniques of forged iron, which he would later use in many of his buildings. He began his career as a designer and sculptor of funeral monuments. From 1879 to 1892 he worked in the office of architect Hendrik Beyaert, where he obtained his architectural training. Under Beyaert, he was chief designer for the Palacio de Chávarri in Bilbao, Spain (1889), constructed for the businessman Víctor Chávarri.

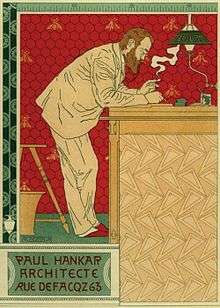

He opened his own office in Brussels in 1893, and began construction of his own house, Hankar House. This and Victor Horta's Hôtel Tassel (constructed at the same time), are considered the first two houses built in the Art Nouveau style. A circa-1894 poster by his friend and frequent collaborator, Adolphe Crespin, advertises Hankar's practice on the Rue Defacqz.

The façade of Hankar House expresses the building's structure—the eastern third, containing the entrance and stairs, is offset a half-story from the western two-thirds, containing the public rooms. A three-story projecting box-bay, supported on stone corbels, provides ample light to the second and third floor rooms and a balcony for the fourth. Mural panels by Crespin appear under the windows and in an arcaded frieze at the eaves. The interplay between heavy Renaissance Revival elements and materials versus light Art Nouveau detailing and decoration results in a vivid composition.

In 1896, he presented a project for a "Cité des Artistes" ("City of Artists") for the seaside town of Westende, an artists' cooperative with housing and studios.[1] Although the project never was realized, it would later inspire the Darmstadt Artists' Colony in Darmstadt, Germany, and the artists of the Vienna Secession.

For the 1897 World's Fair in Brussels, he contributed to the design of the Congo section, which became known for its full employment of the Art Nouveau. He also lectured on "New Brussels," his vision for an urban redevelopment of the city, that was never realized. Later that year, he participated in the Colonial Exposition at Tervuren, Belgium, where he coordinated the works of several artisans and furniture designers.

He designed a monumental stone bench (1898–99), carved by the Ecausines and Soignies quarries, to be exhibited in the Mine and Metallurgy Section of the Exposition Universelle (1900) in Paris. King Leopold II of Belgium bought the bench at the close of the exposition, and donated it to a park in the Koninginlaan neighborhood of Ostend, where it was installed by 1905.[2] The bench was removed in 1971 to expand a parking lot, and destroyed. Using Hankar's surviving drawings, a replica bench was carved for the park (2003–04), and installed on the same foundations as the original.[3]

He was a professor of engineering at the School of Applied Arts in Schaerbeek (1891–97), and a professor of architectural history at the Institut des Hautes Etudes of the University of Brussels (1897–1901). He worked as editor of L'Emulation (1894–96), a magazine that promoted the Art Nouveau style.

Hankar died in Brussels at age 41.

Selected works

Buildings

_JPG01.jpg)

- Mausoleum of Charles Rogier, Saint-Josse-ten-Noode Cemetery, Brussels (187x).

- Palacio de Chávarri, Plaza Moyúa, Bilbao, Spain (1888–89). Designed while Hankar worked in Hendrik Beyaert's office.

- Atelier Alfred Crick (Studio of Alfred Crick), 64 Rue Simonis, Elsene, Brussels (1891).[4]

- Jan van Beers Monument (1891), Antwerp.

- Maison Hankar, 71 Rue Defacqz, Brussels (1893).

- Maisons Jaspar, 76, 78 & 80 Rue de la Croix de Pierre, Brussels (1894).

- Maisons Hanssens, 13 & 15 Avenue Edouard Ducpétiaux, Brussels (1894).[5]

- Maison Zegers-Regnard, 83 Chaussée de Charleroi, Brussels (1894–95).

- 47 Avenue Edouard Ducpétiaux, Brussels (1895).

- Chemiserie Niguet, 13 Rue Royale, Brussels (1896).

- Maison and Pharmacy Peeters, 6-8 Rue Lebeau, Brussels (1896).

- Boulangerie Timmermans, 551 Rue De Herve, Liège (1896, demolished). The three-story façade was covered by murals by Adolphe Crespin.

- Hôtel Renkin, Brussels (1897, demolished).

- Hôtel Ciamberlani, 48 Rue Defacqz, Brussels (1897).

- Sanatorium (1897), Kraainem.

- Hôtel Janssens, 50 Rue Defacqz, Brussels (1898).[6]

- Hôtel Kleyer, 25 Rue de Ruysbroeck, Brussels (1898).

- Maison Aglave, 7 Rue Antoine Bréart, Brussels (1898).

- Maison Bartholomé and its Studio, Brussels (1898, demolished).

- Jean-François Willems Monument, Place Saint-Bavon, Ghent (1899), Isidore De Rudder, sculptor. Hankar designed the pedestal.

- Monumental stone bench – exhibited at the Exposition Universelle (1900) in Paris – (1898–99, demolished 1971). Replica stone bench, Koninginlaan Park, Ostend (2003–04).[7]

Furniture & interiors

- Stool (ca. 1893), Design Museum, Ghent.[8]

- Chair (1896), Royal Museums of Art and History, Brussels.[9] Exhibited at the 1897 Exposition Internationale de Bruxelles.

- Mailbox (1897), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri.[10]

- Coffee table from Hôtel Renkin (1897), Design Museum, Ghent.[11]

- Dining table from Hôtel Ciamberlani (1897), Musée d'Orsay, Paris.[12]

- Sideboard from Hôtel Ciamberlani (1897).[13]

- Card table from Hôtel Ciamberlani (1897).[14]

- Side chair from Hôtel Ciamberlani (1897).[15]

- Swivel chair (ca. 1897).[16]

- Chair with woven leather back (ca. 1897).[17]

- Mahogany dining table (ca. 1897), Galerie Yves Macaux (March 2015).[18]

- Furniture and interiors, American Bar and Grill-Room (1897–98), Grand Hôtel de Bruxelles.

- Stool from Compagnie Générale des Céramiques d'Architecture (1898), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California.[22]

- An identical stool is at Galerie Yves Macaux (March 2015).[23]

- Chair (year), Cinquantenaire Museum, Brussels.[24]

Mausoleum of Charles Rogier, Brussels.

Mausoleum of Charles Rogier, Brussels._1.jpg) Palacio de Chávarri (1888–89), Bilbao, Spain.

Palacio de Chávarri (1888–89), Bilbao, Spain. Studio of Alfred Crick (1891), Brussels.

Studio of Alfred Crick (1891), Brussels. Mural panel on façade of Maison Hankar (1893), Brussels.

Mural panel on façade of Maison Hankar (1893), Brussels. Chemiserie Niguet (1896), Brussels.

Chemiserie Niguet (1896), Brussels.- Hôtel Ciamberlani (1897), Brussels.

- Bas relief panel on façade of Maison Aglave (1898), Brussels.

Stool (1898), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California.

Stool (1898), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California. Willems Monument (1899), Ghent.

Willems Monument (1899), Ghent. Two screens designed for the Grand Hotel. Collection King Baudouin Foundation (depot at Designmuseum Gent-)

Two screens designed for the Grand Hotel. Collection King Baudouin Foundation (depot at Designmuseum Gent-)

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paul Hankar. |

- Project voor een kunstenaarscentrum in Westende 1898.

- Stone bench.

- "De Stenen Bank," Nieuwsblad, 27 July 2011.

- Dossier Atelier Alfred Crick, from Koninklijke Musea voor Kunst en Geschiedenis.

- Maisons Hanssens, from Inventaire du Patrimoine Architectural.

- Hôtel Janssens,

- Replica stone bench, from Pieterbie's Blog.

- Stool, from Design Museum Ghent.

- Chair (scroll down to Figure 14), from Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide.

- Mailbox, from Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

- Coffee table Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, from Design Museum Ghent.

- Dining table, from Musée d'Orsay.

- Sideboard, from Partage Plus.

- Card table Archived 4 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, from Japan Design.

- Side chair Archived 4 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, from Japan Design.

- Swivel chair Archived 26 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, from Piet Hein Eek.

- Chair with woven leather back Archived 26 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, from Piet Hein Eek.

- Mahogany dining table, from Galerie Yves Macaux.

- Pair of folding screens, from Christie's Auctions.

- Pair of folding screens, from Galerie Yves Macaux.

- Tabouret, from Live Autioneers.

- Stool, from LACMA.

- Stool, from Galerie Yves Macaux.

- Chair, from About Art Nouveau.

Further reading

- Charles de Maeyer, Paul Hankar, Mertens, Brussels, 1963.

- Francois Loyer, Paul Hankar: La Naissance de l'Art Nouveau. Archives d'Architecture Modern a Bruxelles. 1986.

- Francois Loyer, Paul Hankar, Architecte: Dix Ans d'Art Nouveau / Ten Years of Art Nouveau. Archives d'Architecture Moderne a Bruxelles. 1991. ISBN 978-2-87-143078-0.

- Francois Loyer, et al., Paul Hankar, Architecte d'Intérieur, Fondation Roi Baudouin. 2005. ISBN 978-2-87212-464-0.