Vickers Jockey

The Vickers Type 151 Jockey was an experimental low-wing monoplane interceptor fighter powered by a radial engine. It was later modified into the Type 171 Jockey II, which had a more powerful engine and detail improvements. Only one was built; it was lost before its development was complete, but the knowledge gained enabled Vickers to produce the more refined Venom.

| Type 151 Jockey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vickers Type 171 Jockey | |

| Role | Interceptor fighter |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Vickers Ltd. |

| Designer | Rex Pierson and J. Bewsher |

| First flight | April 1930 |

| Number built | 1 |

| Variants | Vickers Venom |

Development

In the late 1920s the idea of the interceptor fighter was forming. To deal with the faster and higher flying bombers, fighters had both to be fast at height and quick to get there. The Air Ministry was keen to determine the best aircraft configuration and sought, under Air Ministry specification F.20/27, manufacturers to build biplanes and both low- and high-wing monoplanes. Vickers were asked for a prototype low-wing fighter and this became (somewhat unofficially) called the "Jockey", or sometimes the Jockey I. The name covered Vickers Types 151 and 171; the Jockey II was an early name for the later Venom.[1]

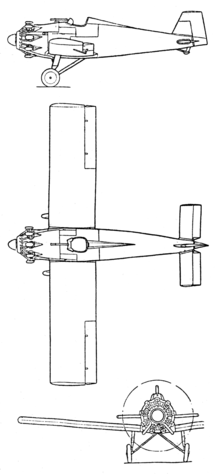

The Type 151 Jockey was a compact and rather angular, low cantilever wing monoplane, built using the Wibault-Vickers corrugated skinned all-metal method as used on the Vireo. The unstressed skin was riveted onto a largely duralumin structure, a few steel tubes forming highly stressed members. The parallel chord, square-tipped wing used the thick, high-lift RAF 34 cross-section that Vickers had employed on the Viastra. The tailplane was equally rectangular and the fin clipped. All control surfaces apart from the rudder were unbalanced. The pilot's open cockpit was at the highest part of the fuselage at mid-chord. The 480 horsepower (360 kW) Bristol Mercury IIA nine-cylinder radial was initially mounted without a cowling. A single-axle undercarriage had legs attached to front and rear wing spars.[1]

The Jockey was taken to RAF Martlesham Heath for its first flight in April 1930 and subsequent testing.[2] A rear fuselage vibration was at first thought to be aerodynamic but proved to be structural; it was cured after Barnes Wallis redesigned the internal bracing. The rudder was modified, its balance removed and a trim tab installed. Spats were added to the undercarriage and a Townend ring enclosed the engine. The same aircraft was renamed the Type 171 Jockey when the Mercury was replaced by a 530 horsepower (400 kW) supercharged Bristol Jupiter VIIF. The intention to power the Jockey with a supercharged Mercury IVS2 was never realised, after the sole Jockey was lost in a flat spin on 5 July 1932, crashing at Woodbridge, Suffolk, the pilot bailing out at 5,000 feet (1,500 m).[3] The results of the tests had been sufficiently good to encourage Vickers to refine its design into the Vickers Venom.[1]

Variants

- Type 151 Jockey

- Prototype single-seat fighter, one only (J9122).

- Type 171 Jockey

- Modified Type 151 with revised rear fuselage and powered by Jupiter VIIF engine enclosed in Townsend ring.

- Type 196 Jockey III

- Single-seat fighter, same engine as Type 171. Started but not completed. Registered G-AAWG reserved by Vickers 5 April 1933.[4]

Specifications (Type 171)

Data from [5]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 23 ft 0 in (7.01 m)

- Wingspan: 23 ft 6 in (7.16 m)

- Height: 8 ft 3 in (2.51 m)

- Wing area: 150 sq ft (14 m2)

- Aspect ratio: 6.22:1[6]

- Airfoil: RAF 34[6]

- Empty weight: 2,260 lb (1,025 kg)

- Gross weight: 3,161 lb (1,434 kg)

- Powerplant: × Bristol Jupiter VIIF nine-cylinder air-cooled radial engine, 530 hp (400 kW)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 218 mph (351 km/h, 189 kn) at 10,000 ft (3,000 m)

- Service ceiling: 31,000 ft (9,400 m) (absolute)

- Rate of climb: 1,850 ft/min (9.4 m/s) (initial)

- Time to altitude: 4.8 minutes to 10,000 ft (3,000 m)

Armament

- Guns: 2× .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers machine guns

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vickers Jockey. |

Notes

- Andrews & Morgan 1988, pp. 238–41, 254, 515

- Andrews & Morgan 1988, pp. 240–1

- Mason 1992, p. 228

- Andrews & Morgan 1988, p. 515

- Andrews & Morgan 1988, p. 254

- Lumsden & Heffernan 1983, p. 17

Bibliography

- Andrews, C. F.; Morgan, E. B. (1988). Vickers Aircraft since 1908 (2nd ed.). London: Putnam. ISBN 0-85177-815-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lumsden, Alec; Heffernan, Terry (January 1983). "Probe Probare: Part 1". Aeroplane Monthly. Vol. 12 no. 1. pp. 14–17. ISSN 0143-7240.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mason, Francis K. (1992). The British Fighter since 1912. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-082-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)