Recipe

A recipe is a set of instructions that describes how to prepare or make something, especially a dish of prepared food.

The term recipe is also used in medicine or in information technology (e.g., user acceptance). A doctor will usually begin a prescription with recipe, Latin for take, usually abbreviated as Rx or the equivalent symbol (℞).

History

Early examples

The earliest known written recipes date to 1730 BC and were recorded on cuneiform tablets found in Mesopotamia.[1]

Other early written recipes date from approximately 1600 BC and come from an Akkadian tablet from southern Babylonia.[2] There are also works in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs depicting the preparation of food.[3]

Many ancient Greek recipes are known. Mithaecus's cookbook was an early one, but most of it has been lost; Athenaeus quotes one short recipe in his Deipnosophistae. Athenaeus mentions many other cookbooks, all of them lost.[4]

Roman recipes are known starting in the 2nd century BCE with Cato the Elder's De Agri Cultura. Many authors of this period described eastern Mediterranean cooking in Greek and in Latin.[4] Some Punic recipes are known in Greek and Latin translation.[4]

The large collection of recipes De re coquinaria, conventionally titled Apicius, appeared in the 4th or 5th century and is the only complete surviving cookbook from the classical world.[4] It lists the courses served in a meal as Gustatio (appetizer), Primae Mensae (main course) and Secundae Mensae (dessert).[5] Each recipe begins with the Latin command "Take...," "Recipe...."[6]

Arabic recipes are documented starting in the 10th century; see al-Warraq and al-Baghdadi.

The earliest recipe in Persian dates from the 14th century. Several recipes have survived from the time of Safavids, including Karnameh (1521) by Mohammad Ali Bavarchi, which includes the cooking instruction of more than 130 different dishes and pastries, and Madat-ol-Hayat (1597) by Nurollah Ashpaz.[7] Recipe books from the Qajar era are numerous, the most notable being Khorak-ha-ye Irani by prince Nader Mirza.[8]

King Richard II of England commissioned a recipe book called Forme of Cury in 1390,[9] and around the same time, another book was published entitled Curye on Inglish, "cury" meaning cooking.[10] Both books give an impression of how food for the noble classes was prepared and served in England at that time. The luxurious taste of the aristocracy in the Early Modern Period brought with it the start of what can be called the modern recipe book. By the 15th century, numerous manuscripts were appearing detailing the recipes of the day. Many of these manuscripts give very good information and record the re-discovery of many herbs and spices including coriander, parsley, basil and rosemary, many of which had been brought back from the Crusades.[11]

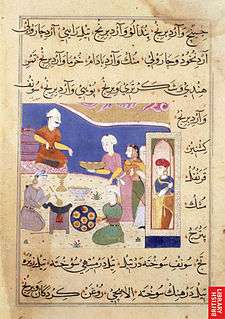

A page from the Nimmatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi, book of delicacies and recipes. It documents the fine art of making kheer.

A page from the Nimmatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi, book of delicacies and recipes. It documents the fine art of making kheer. Medieval Indian Manuscript (circa 16th century) showing samosas being served.

Medieval Indian Manuscript (circa 16th century) showing samosas being served.

Modern recipes and cooking advice

With the advent of the printing press in the 16th and 17th centuries, numerous books were written on how to manage households and prepare food. In Holland[12] and England[13] competition grew between the noble families as to who could prepare the most lavish banquet. By the 1660s, cookery had progressed to an art form and good cooks were in demand. Many of them published their own books detailing their recipes in competition with their rivals.[14] Many of these books have been translated and are available online.[15]

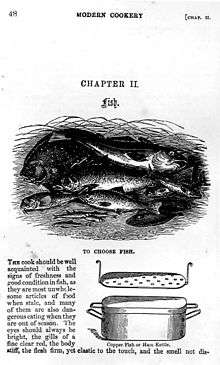

By the 19th century, the Victorian preoccupation for domestic respectability brought about the emergence of cookery writing in its modern form. Although eclipsed in fame and regard by Isabella Beeton, the first modern cookery writer and compiler of recipes for the home was Eliza Acton. Her pioneering cookbook, Modern Cookery for Private Families published in 1845, was aimed at the domestic reader rather than the professional cook or chef. This was immensely influential, establishing the format for modern writing about cookery. It introduced the now-universal practice of listing the ingredients and suggested cooking times with each recipe. It included the first recipe for Brussels sprouts.[16] Contemporary chef Delia Smith called Acton "the best writer of recipes in the English language."[17] Modern Cookery long survived Acton, remaining in print until 1914 and available more recently in facsimile.

Acton's work was an important influence on Isabella Beeton,[18] who published Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management in 24 monthly parts between 1857 and 1861. This was a guide to running a Victorian household, with advice on fashion, child care, animal husbandry, poisons, the management of servants, science, religion, and industrialism.[19][20] Of the 1,112 pages, over 900 contained recipes. Most were illustrated with coloured engravings. It is said that many of the recipes were plagiarised from earlier writers such as Acton, but the Beetons never claimed that the book's contents were original. It was intended as a reliable guide for the aspirant middle classes.

The American cook Fannie Farmer (1857–1915) published in 1896 her famous work The Boston Cooking School Cookbook which contained some 1,849 recipes.[21]

Components

Modern culinary recipes normally consist of several components

- The name of the recipe (Origins/History of the dish)

- Yield: The number of servings that the dish provides.

- List all ingredients in the order of its use. Describe it in step by step instructions.

- Listing ingredients by the quantity (Write out abbreviations. Ounces instead of oz).

- How much time does it take to prepare the dish, plus cooking time for the dish.

- Necessary equipment used for the dish.

- Cooking procedures. Temperature and bake time if necessary.

- Serving procedures (Served while warm/cold).

- Review of the dish (Would you recommend this dish to a friend?).

- Photograph of the dish (Optional).

- Nutritional Value: Helps for dietary restrictions. Includes number of calories or grams per serving.

Earlier recipes often included much less information, serving more as a reminder of ingredients and proportions for someone who already knew how to prepare the dish.[22][23]

Recipe writers sometimes also list variations of a traditional dish, to give different tastes of the same recipes.

Internet and television recipes

By the mid 20th century, there were thousands of cookery and recipe books available. The next revolution came with the introduction of the TV cooks. The first TV cook in England was Fanny Cradock with a show on the BBC. TV cookery programs brought recipes to a new audience. In the early days, recipes were available by post from the BBC; later with the introduction of CEEFAX text on screen, they became available on television.

The first Internet Usenet newsgroup dedicated to cooking was net.cooks created in 1982, later becoming rec.food.cooking.[24] It served as a forum to share recipes text files and cooking techniques.

In the early 21st century, there has been a renewed focus on cooking at home due to the late-2000s recession.[25] Television networks such as the Food Network and magazines are still a major source of recipe information, with international cooks and chefs such as Jamie Oliver, Gordon Ramsay, Nigella Lawson and Rachael Ray having prime-time shows and backing them up with Internet websites giving the details of all their recipes. These were joined by reality TV shows such as Top Chef or Iron Chef, and many Internet sites offering free recipes, [Healthies.Recipes].[26].

Recipe design tools

Molecular gastronomy provides chefs with cooking techniques and ingredients, but this discipline also provides new theories and methods which aid recipe design. These methods are used by chefs, foodies, home cooks and even mixologists worldwide to improve or design recipes.

See also

- Cookbook

- Course (food)

- Culinary art

- hRecipe - a microformat for marking-up recipes in web pages

- List of desserts

- List of foods

- Rhyming recipe

References

- Winchester, Ashley. "The world's oldest-known recipes decoded". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- Jean Bottéro, Textes culinaires Mésopotamiens, 1995. ISBN 0-931464-92-7; commentary at Society of Biblical Literature

- Ancient Egyptian cuisine

- Andrew Dalby, Food in the Ancient World from A to Z, 2003. ISBN 0-415-23259-7 p. 97-98.

- "Roman food in Britain". Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- Colquhoun, Kate (2008) [2007]. Taste: The Story of Britain through its Cooking. Bloomsbury. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-747-59306-5.

- Jaam-e Jam

- "کتاب خوراک های ایرانی". مجله تصویری فرهنگ غذا (in Persian). December 3, 2016. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- COMDA Calendar Co. 2007 Recipe Calendar. COMDA, Canada.

- Hicatt, Constance B; Sharon Butler (1985). English Culinary Manuscripts of the 14C.

- Austin, Thomas (1888). Ashmole and other Manuscripts.

- Sieben, Ria Jansen (1588). Een notable boecxtken van cokeryen.

- anon (1588). The good Huswifes handmaid for Cookerie.

- May, Robert (1685). The accomplifht Cook.

- Judy Gerjuoy. "Medieval Cookbooks". Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- Pearce, Food For Thought: Extraordinary Little Chronicles of the World, (2004) pg 144

- Interview.

- Acton, Eliza (1799–1859). Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Gale Research Inc. January 2002. Archived from the original on 2013-05-18. Retrieved 8 January 2013.(subscription required)

- General Observations on the Common Hog

- Food in season in April 1861

- Cunningham, Marion (1979). The Fannie Farmer Cookbook (revised). Bantam Books, New York. ISBN 978-0-553-56881-3.

- Paradowski, Michał B. (2010). Through catering college to the naked chef – teaching LSP and culinary translation. In: Bogucki, Łukasz (Ed.) Teaching Translation and Interpreting: Challenges and Practices. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press. pp. 137–165.

- Paradowski, Michał B. (2017). "What's cooking in English culinary texts? Insights from genre corpora for cookbook and menu writers and translators". The Translator. 24: 50–69. doi:10.1080/13556509.2016.1271735.

- Sack, Victor (20 October 2016), rec.food.cooking FAQ and conversion file, sec. 6.1

- Holmes, Elizabeth (2009-05-05). "Web Recipes Are Cooking With Gas". Wall Street Journal.

- Sack, Victor (4 June 2020), Homemade Cake Recipe, sec. 6.1

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |