Bibliothèque Mazarine

The Bibliothèque Mazarine, or Mazarin Library, is located within the Palais de l'institut de France, or the Palace of the Institute of France (previously the Collège des Quatre-Nations of the University of Paris), at 23 quai de Conti in the 6th arrondissement, on the Left Bank of the Seine facing the Pont des Arts and the Louvre. Originally created by Cardinal Mazarin as his personal library in the 17th century, it today has one of the richest collections of rare books and manuscripts in France, and is the oldest public library in the country.

History

The founder of the library, Cardinal Jules Raymond Mazarin (1602-1661), was born Giulio Ramondo Mazzarino in Pescina in the Kingdom of Naples, into a noble but poor family[1]. He went into the church, studied at the Jesuit College in Rome, though he declined to join their order. He went into the Papal service, where he became known for his diplomatic, political and military skills, and was assigned as a nuncio to the French Court from 1634 to 1636. His talents brought him to the elder Cardinal Richelieu, the chief minister of Louis XIII, who made him a member of the council of State of the King. When he came from Rome to Paris, he brought with him an impressive library of five thousand books which he had kept in his palace on mont Quirinal in Rome.[2]

With the death of Louis XIII in 1643, he became the new Prime Minister, with the support of the Queen, Anne of Austria. He immediately began constructing a palace for himself on rue de Richelieu in Paris, with an enormous chamber fifty-eight meters long designed especially to house his library. Visitors, including Frederick III, the King of Denmark, came from around Europe to see his library, and to model their own royal libraries after his. Between 1642 and 1653, Mazarin's librarian, Gabriel Naudé, traveled to Italy, Switzerland, Germany, England and Holand, buying entire libraries for Mazarin's collection, making it the largest library in Europe at the time, with forty thousand volumes.[3]

The library nearly came to an end in January and February 1652 with the outbreak of the Fronde, an uprising by several powerful nobles against the authority of Mazarin. Mazarin and the young King were forced to flee Paris. The palace was looted and thousands of books were burned, lost or sold. Fortunately Naudé succeeded in hiding the most valuable volumes in his apartment in the Abbey of Saint-Genevieve. When Mazarin was finally able to return to Paris and to power in 1653, Naudé was able to get back many of the books which had been sold or stolen. [4]

He then began a second library with what was left of the first, assisted by the successor to Naudé, François de La Poterie. Since 1643, Mazarin had opened his library to scholars. It was open on Thursdays, and each week some eighty to one hundred came to do research. By the 1660s, the library held 25,000 volumes.[5] The collection was matched by only three other libraries in Europe; the Bodleian Library of Oxford; the Ambrosian Library in Milan and the Angelique Library in Rome.

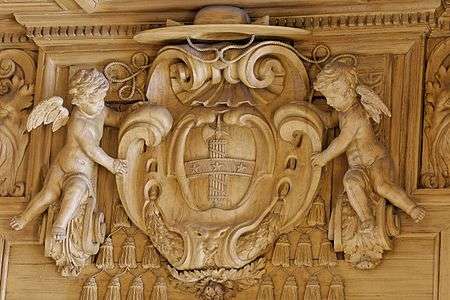

After his experience with the Fronde, Mazarin wanted to assure that his library remained intact after his death. In his will written March 6, 1661, three days before his death, he bequeathed his library to the Collège des Quatre-Nations a new college of the University of Paris that he founded for the sons of noble families from four provinces recently added to France. The new library building was constructed on the exact site of the medieval Tour de Nesle, or Nesle Tower, on the banks of the Seine. On the fronton is the inscription in Latin: Bibliotheca a fundatore mazarinea (Library founded by Mazarin). The original bookcases of his library, decorated with carved Corinthian columns and with the coat of arms of the Cardinal, were moved to the new location in the east wing of the College, along rue de Richelieu. The new library opened for Easter in 1689. [6]

The library continued to grow during the 18th century, from 36,000 volumes in 1730 to 50,000 in 1771. The French Revolution did no harm to the collection, and in fact greatly increased its size; the librarian, Gaspard Michel, bought books which had been confiscated from monasteries and from nobles who had gone into exile, and increased the collection to more than 60,000 volumes. He also collected works of art, mostly from the 17th and 18th centuries, gilded bronze chandeliers, Louis XVI commodes, a globe of the heavens by Gastellier from 1694, and other objects which decorate the reading room today.

In 1805, under Napoleon I, The Collège des Quatre-Nations became the Palace of the Institut de France, the headquarters of the French scholarly and scientific academies. Since that time the Library has received donations of numerous large collections, and since 1926 has also been the depository of publications relating to the history of the regions of France.

The Collections

The library today contains about 600,000 volumes. The oldest part of the collection, brought together by Mazarin, contains about 200,000 volumes on all subjects. The more modern collections specialize in French history, particularly religious and literary history of the Middle Ages (12th-15th centuries) and the 16th and 17th centuries. Other specialities are the history of the book and the local and regional history of France.

Among the library's collection of 2,370 incunabula is a Gutenberg Bible known as the Bible Mazarine. The original is kept in a vault, while a facsimile copy is on display in the reading room.

The manuscript collection of Mazarin comes from an exchange made in 1668 with the Royal Library of France (now the National Library of France. The collection now contains 4 600 manuscripts, including 1,500 medieval manuscripts, many of which are illuminated, which were largely confiscated from French nobles after the French Revolution. It also has the most important collection of the Mazarinade, a type of political tract from the period of the Fronde.

In the 19th and 20th centuries the library received donations of important collections, including the archives of Pierre-Antoine Lebrun, Joseph Tastu, Arsène Thiébaut de Berneaud; and the library and archives of the scientists Albert Demangeon and of Aimé Perpillou (geography); the library of Marcel Chatillon (History of the Antilles) and a part of the archives of the Chevalier de Paravey (voyages); of Jean-Jacques Ampère (Nordic civilizations) and of Prosper Faugère (Pascal and Jansenism).

Access

The Library is located at 23 quai de Conti. It is open to the public every day except Saturdays, Sundays and holidays from 10:00 until 18:00. it is closed each summer from August 1 until August 15.

References

Notes and citations

- Poncet, Olivier (2018). Mazarin l'Italien (in French). Paris: Tallandier. ISBN 979-10-210-3105-0.

- Péligry 1995, p. 28.

- Péligry 1995, pp. 28–29.

- Péligry 1995, p. 29.

- 1948-, Murray, Stuart (2009). The library : an illustrated history. New York, NY: Skyhorse Pub. pp. 122. ISBN 9781602397064. OCLC 277203534.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Péligry 1995, p. 32.

Bibliography

- Péligry, Christian (1995). Le palais d'Institut de France- La Bibliothèque Mazarine. Beaux Arts Magazine/Institut de France.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Edward Edwards. Memoirs of libraries including a handbook of Library economy. v.2. London: Trübner, 1859

- A. Franklin, Histoire de la bibliothèque Mazarine, 2e éd., Paris, H. Welter, 1901 (1st edition, 1860)

- Adolphe Joanne. The Diamond Guide for the stranger in Paris. Paris: Hachette, 1867

- "Mazarine Library." Report of the Fifteenth Annual Meeting of the Library Association of the United Kingdom: ... held in Paris ... 1892. London: 1893

- M. Piquard, " La bibliothèque de Mazarin et la Bibliothèque Mazarine, 1643–1804 ", in: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Compte-rendus des séances de l’année 1975, janvier-mars, 1975, p. 129–30.

- P. Gasnault, " De la bibliothèque de Mazarin à la Bibliothèque Mazarine ", in: Histoire des bibliothèques françaises. Les bibliothèques sous l’Ancien Régime, 1530–1789, 1988

- La Bibliothèque Mazarine, no 222 (déc. 2000-janv./fév. 2001) of Arts et métier du livre

- David H. Stam, ed. (2001). "Mazarine Library". International Dictionary of Library Histories. Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 1-57958-244-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bibliothèque Mazarine. |

- (in French) Site Internet de la bibliothèque (French)