Vein matching

Vein matching, also called vascular technology,[1] is a technique of biometric identification through the analysis of the patterns of blood vessels visible from the surface of the skin.[2] Though used by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Central Intelligence Agency,[3] this method of identification is still in development and has not yet been universally adopted by crime labs as it is not considered as reliable as more established techniques, such as fingerprinting. However, it can be used in conjunction with existing forensic data in support of a conclusion.[2][4]

| Part of a series on |

| Forensic science |

|---|

|

|

While other types of biometric scanners are more popular for security systems, vascular scanners are growing in popularity. Fingerprint scanners are more frequently used, but they generally do not provide enough data points for critical verification decisions. Since fingerprint scanners require direct contact of the finger with the scanner, dry or abraded skin can interfere with the reliability of the system. Skin diseases, such as psoriasis, can also limit the accuracy of the scanner, not to mention direct contact with the scanner can result in need for more frequent cleaning and higher risk of equipment damage. Vascular scanners do not require contact with the scanner, and since the information they read is on the inside of the body, skin conditions do not affect the accuracy of the reading. Vascular scanners also work with extreme speed, scanning in less than a second. As they scan, they capture the unique pattern veins take as they branch through the hand. Compared to the retinal scanner, which is more accurate than the vascular scanner, the retinal scanner has much lower popularity, because of its intrusive nature. People generally are uncomfortable exposing their eyes to an unknown light, not to mention retinal scanners are more difficult to install, since variances in height and face angle must be accounted for.[5]

History

Joe Rice, an automation controls engineer at Kodak's Annesley Factory, invented vein pattern recognition in the early 1980s in response to his bank cards and identity being stolen. He developed essentially a barcode reader for people and assigned the rights to the UK's NRDC (National Research Development Corporation).[6] The NRDC/ BTG (Thatcher privatised NRDC into BTG) made little headway in licensing vein pattern technology. The world was wedded to fingerprints and Iris patterns and Governments (the main buyers of biometric solutions) wanted open view biometrics for surveillance purposes, not a hidden, personal biometric solution.

In the late 1990s BTG said they were dropping vein patterns through no commercial interest. Rice was unhappy with the BTG's decision and their implementation of vein pattern technology so he gave a talk at the Biometric Summit in Washington DC, on how he would develop vein pattern recognition.[7] This view was countered by a following speaker from IBG (The US based international Biometric Group) who said there was insufficient information content in vein patterns for them to be used as a viable biometric.

In 2002 Hitachi and Fujitsu launched vein biometric products and veins have turned out to be one of the most consistent, discriminatory and accurate biometric traits.

In the mid 2000s, Rice received an invitation from Matthias Vanoni to partner in a Swiss company Biowatch SA to develop and commercialise the biowatch.

Commercial applications

Vascular/vein pattern recognition (VPR) technology has been developed commercially by Hitachi since 1997, in which infrared light absorbed by the haemoglobin in a subject's blood vessels is recorded (as dark patterns) by a CCD camera behind a transparent surface.[8] The data patterns are processed, compressed, and digitized for future biometric authentication of the subject. Finger scanning devices have been deployed for use in Japanese financial institutions, kiosks, and turnstiles.[9] Mantra Softech marketed a device in India that scans vein patterns in palms for attendance recording.[10] Fujitsu developed a version that does not require direct physical contact with the vein scanner for improved hygiene in the use of electronic point of sale devices.[11]

Computer security expert Bruce Schneier stated that a key advantage of vein patterns for biometric identification is the lack of a known method of forging a usable "dummy", as is possible with fingerprints.[12]

Forensic identification

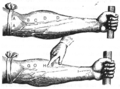

According to a 31,000-word investigative report published in January 2011 by Georgetown University faculty and students,[13][14][15][16][17] U.S. federal investigators used photos from the video recording of the beheading of American journalist Daniel Pearl to match the veins on the visible areas of the perpetrator to that of captured al-Qaeda operative Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, notably a "bulging vein" running across his hand.[4] The FBI and the CIA used the matching technique on Mohammed in 2004 and again in 2007.[3] Officials were concerned that his confession, which had been obtained through torture (namely waterboarding), would not hold up in court and used vein matching evidence to bolster their case.[2]

Other applications

Some US hospitals, such as NYU Langone Medical Center, use a vein matching system called Imprivata PatientSecure, primarily to reduce errors. Additional benefits include identifying unconscious or uncommunicative patients, and saving time and paperwork.[18] Dr. Bernard A. Birnbaum, chief of hospital operations at Langone, says "vein patterns are 100 times more unique than fingerprints".[19] However, the newspaper reports of the use of vein matching to determine whether Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was Mr Pearl's murderer quoted FBI officials who described the technique as "less reliable" than fingerprints.

References

- Finn, Peter (20 January 2011). "Report: Top al-Qaeda figure killed Pearl". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- Blackburn, Bradley (20 January 2011). "Report Says Justice Not Served in Murder of Daniel Pearl, Wall Street Journal Reporter". ABC News. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- Cratty, Carol (20 January 2011). "Photos of hands backed up Pearl slaying confession, report finds". CNN. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- Ackerman, Spencer (20 January 2011). "Qaeda Killer's Veins Implicate Him In Journo's Murder". Wired. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- Bryn Nelson (30 June 2008). "Giving biometrics a hand". nbcnews.com. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- See his website from 1993 onwards at: https://sites.google.com/site/veinpatternhome/

- His original patent on vein matching Google "WO1985004088A1"

- His US Patent on Vein Matching issued 1987 Google "US patent 4699149"

- Details of his 1990 Smart door handle

- His biometric Summit Talk Google "A third way for Biometrics"

- His predictions for the future of Vein pattern technology: http://biometrics.mainguet.org/types/vein_JoeRice.htm

- ""A Third Way for Biometrics" –Google Groups". groups.google.com.

- "HRSID Vein Recognition overview".

- "Finger Vein Authentication Technology". Hitachi America, Ltd. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- "PV2000". India: Mantra Softech Pvt. Ltd. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- "Your hand is the key: The world's first contactless palm vein authentication technology". PalmSecure. Fujitsu. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- Schneier, Bruce (8 August 2007). "Another Biometric: Vein Patterns". Schneier on Security. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- Stanglin, Douglas (20 January 2011). "Report: Forensic evidence ties 9/11 plotter to Pearl's killing". USA Today. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

-

Benjamin Wittes (20 January 2011). "So KSM Really Did Kill Daniel Pearl". Lawfare. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

The investigation produced a lengthy report concluding, among other things, that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was telling the truth when he boasted at his CSRT hearing of “decapitat[ing] with my blessed right hand the head of the American Jew, Daniel Pearl.”

- Asra Q. Nomani; et al. (20 January 2011). "The Pearl Project". The Center for Public Integrity. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

-

Peter Finn (20 January 2011). "Khalid Sheik Mohammed killed U.S. journalist Daniel Pearl, report finds". Washington Post. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

A recently completed investigation of the killing of Daniel Pearl in Pakistan nine years ago makes public new evidence that a senior al-Qaeda operative executed the Wall Street Journal reporter.

-

Ben Farmer (20 January 2011). "Daniel Pearl was beheaded by 9/11 mastermind". The Telegraph (UK). Retrieved 10 October 2013.

They replied: 'The photo you sent me and the hand of our friend inside the cage seem identical to me.' Both the CIA and FBI use the mathematical modelling technique, though it is not considered as reliable as fingerprinting.

- Allen, Jonathan (28 July 2011). "New York hospital using palm-scanners". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- By Plasencia, Amanda (28 July 2011). "Hospital Scans Patient Hands to Pull Medical Info". NBC New York. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

Further reading

- Prasanalakshmi, Balaji; Sampath, Kannammal (2009). "A secure cryptosystem from palm vein biometrics". Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interaction Sciences: Information Technology, Culture and Human.

- Watanabe, Masaki; Shiohara, Morito; Sasaki, Shigeru (September 2005). "Palm vein authentication technology and its applications" (PDF). Proceedings of the Biometric Consortium Conference.

- Zhang, Yi-Bo; Li, Qin; You, Jane; Bhattacharya, Prabir (2007). Palm Vein Extraction and Matching for Personal Authentication. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 4781. Concordia University. pp. 154–164. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-76414-4_16. ISBN 978-3-540-76413-7.

- Chen, Liukui; Zheng, Hong (May 2009). Finger Vein Image Recognition Based on Tri-value Template Fuzzy Matching (PDF). Proceedings of the 9th WSEAS International Conference on Multimedia Systems & Signal Processing. Wuhan University. pp. 206–211. ISBN 978-960-474-077-2. ISSN 1790-5117.

- Kumar, A.; Prathyusha, K.V. (September 2009). "Personal Authentication Using Hand Vein Triangulation and Knuckle Shape". IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 18 (9): 2127–2136. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.606.1087. doi:10.1109/TIP.2009.2023153. ISSN 1057-7149. PMID 19447728.

- Chen, Haifen; Lu, Guangming; Wang, Rui (December 2009). A new palm vein matching method based on ICP algorithm. International Conference on Information Systems. Harbin Institute of Technology. pp. 1207–1211. doi:10.1145/1655925.1656145. ISBN 978-1-60558-710-3.