Valperga (novel)

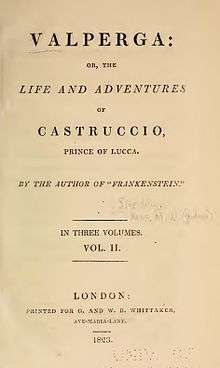

Valperga: or, the Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca is an 1823 historical novel by the Romantic novelist Mary Shelley, set amongst the wars of the Guelphs and Ghibellines (the latter of which she spelled "Ghibeline").

Publication details

Mary Shelley's original title is now the subtitle; Valperga was selected by her father, William Godwin, who edited the work for publication between 1821 and February 1823. His edits emphasised the female protagonist and shortened the novel.[1]

Plot summary

Valperga is a historical novel which relates the adventures of the early fourteenth-century despot Castruccio Castracani, a real historical figure who became the lord of Lucca and conquered Florence. In the novel, his armies threaten the fictional fortress of Valperga, governed by Countess Euthanasia, the woman he loves. He forces her to choose between her feelings for him and political liberty. She chooses the latter and sails off to her death.

Themes

Through the perspective of medieval history, Mary Shelley addresses a live issue in post-Napoleonic Europe, the right of autonomously governed communities to political liberty in the face of imperialistic encroachment.[2] She opposes Castruccio's compulsive greed for conquest with an alternative, Euthanasia's government of Valperga on the principles of reason and sensibility.[3] In the view of Valperga's recent editor Stuart Curran, the work represents a feminist version of Walter Scott's new and often masculine genre, historical novel.[4] Modern critics draw attention to Mary Shelley's republicanism, and her interest in questions of political power and moral principles.[5]

Reception

Valperga earned largely positive reviews, but it was judged as a love story, its ideological and political framework overlooked.[6] It was not, however, republished in Mary Shelley's lifetime, and she later remarked that it never had "fair play".[7] Recently, Valperga has been praised for its sophisticated narrative form and its authenticity of detail.[8]

In 1824, a reviewer for Knight's Quarterly Review compared Valperga and Frankenstein and alleged that each novel was written by a different author:

"[T]here is not the slightest trace of the same hand -- instead of the rapidity and enthusiastic energy which hurries you forward in Frankenstein, every thing is cold, crude, inconsecutive, and wearisome; -- not one flash of imagination, not one spark of passion -- opening it as I did, with eager expectation, it must indeed have been bad for me after toiling a week to send the book back without having finished the first volume. This induced me to read Frankenstein again -- for I thought I must have been strangely mistaken in my original judgment. So far, however, from this, a second reading has confirmed it. I think Frankenstein possesses extreme power, and displays capabilities such as I did hope would have produced far different things from Castruccio]]. ... But whence arises the extreme inferiority of Valperga? I can account for it only by supposing that Shelley wrote the first, though it was attributed to his wife, -- and that she really wrote the last. … It has much of his poetry and vigour … At all events, the difference of the two books is very remarkable."

— [9]

Notes

- Rossington, Introduction to Valperga, xv; Curran, 103.

- Curran, 108-11.

- Rossington, Introduction to Valperga, xii.

- Curran, 106-07.

- Bennett, An Introduction, 60.

- Bennett, An Introduction, 60–61.

- Rossington, Introduction to Valperga, xxiv.

- Curran, 104-06. Mary Shelley, as Percy Shelley confirmed, "visited the scenery which she described in person", and consulted many books about Castruccio and his times.

- “Frankenstein’’, Knight's Quarterly Review, 3 (August, 1824), edited by Charles Knight: 195-99.

Bibliography

- Bennett, Betty T. Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley: An Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8018-5976-X.

- Bennett, Betty T. "Machiavelli's and Mary Shelley's Castruccio: Biography as Metaphor. Romanticism 3.2 (1997): 139–51.

- Bennett, Betty T. "The Political Philosophy of Mary Shelley's Historical novels: Valperga and Perkin Warbeck". The Evidence of the Imagination. Eds. Donald H. Reiman, Michael C. Jaye, and Betty T. Bennett. New York: New York University Press, 1978.

- Blumberg, Jane. Mary Shelley's Early Novels: "This Child of Imagination and Misery". Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1993. ISBN 0-87745-397-7.

- Brewer, William D. "Mary Shelley's Valperga: The Triumph of Euthanasia's Mind". European Romantic Review 5.2 (1995): 133–48.

- Carson, James P. "'A Sigh of Many Hearts': History, Humanity, and Popular Culture in Valperga". Iconoclastic Departures: Mary Shelley after "Frankenstein": Essays in Honor of the Bicentenary of Mary Shelley's Birth. Eds. Syndy M. Conger, Frederick S. Frank, and Gregory O'Dea. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997.

- Clemit, Pamela. The Godwinian Novel: The Rational Fictions of Godwin, Brockden Brown, Mary Shelley. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993. ISBN 0-19-811220-3.

- Curran, Stuart. "Valperga". The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley. Ed. Esther Schor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-00770-4.

- Lew, Joseph W. "God's Sister: History and Ideology in Valperga". The Other Mary Shelley: Beyond Frankenstein. Eds. Audrey A. Fisch, Anne K. Mellor, and Esther H. Schor. New York: New York University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-19-507740-7.

- O'Sullivan, Barbara Jane. "Beatrice in Valperga: A New Cassandra". The Other Mary Shelley: Beyond Frankenstein. Eds. Audrey A. Fisch, Anne K. Mellor, and Esther H. Schor. New York: New York University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-19-507740-7.

- Lokke, Kari. "'Children of Liberty': Idealist Historiography in Staël, Shelley, and Sand". PMLA 118.3 (2003): 502–20.

- Lokke, Kari. "Sibylline Leaves: Mary Shelley's Valperga and the Legacy of Corinne". Cultural Interactions in the Romantic Age: Critical Essays in Comparative Literature. Ed. Gregory Maertz, Gregory. New York: State University of New York Press, 1998.

- Poovey, Mary. The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer: Ideology as Style in the Works of Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley and Jane Austen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985. ISBN 0-226-67528-9.

- Rajan, Rilottama. "Between Romance and History: Possibility and Contingency in Godwin, Leibniz, and Mary Shelley's Valperga". Mary Shelley in Her Times. Eds. Betty T. Bennett and Stuart Curran. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- Rossington, Michael. "Future Uncertain: The Republican Tradition and its Destiny in Valperga". Mary Shelley in Her Times. Eds. Betty T. Bennett and Stuart Curran. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- Schiefelbein, Michael. "'The Lessons of True Religion': Mary Shelley's Tribute to Catholicism in Valperga". Religion and Literature 30.2 (1998): 59–79.

- Shelley, Mary. Valperga; or, The Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca. Ed. Michael Rossington. Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks, 2000. ISBN 0-19-283289-1.

- Shelley, Mary. Valperga; or, The Life and Adventures of Castruccio, Prince of Lucca. The Novels and Selected Works of Mary Shelley. Vol. 3. Ed. Nora Crook. London: Pickering and Chatto, 1996.

- Sunstein, Emily W. Mary Shelley: Romance and Reality. 1989. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-8018-4218-2.

- Wake, Ann M. Frank. "Women in the Active Voice: Recovering Female History in Mary Shelley's Valperga and Perkin Warbeck". Iconoclastic Departures: Mary Shelley after "Frankenstein": Essays in Honor of the Bicentenary of Mary Shelley's Birth. Eds. Syndy M. Conger, Frederick S. Frank, and Gregory O'Dea. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997.

- White, Daniel E. "'The God Undeified': Mary Shelley's Valperga, Italy, and the Aesthetic of Desire". Romanticism on the Net 6 (Mary 1997).

- Williams, John. "Translating Mary Shelly's Valperga into English: Historical Romance, Biography or Gothic Fiction?". European Gothic: A Spirited Exchange, 1760–1960. Ed. Avril Horner. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002.