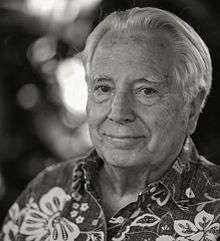

V. H. Viglielmo

Valdo H. Viglielmo (December 11, 1926 - November 14, 2016) was a prominent scholar and translator of Japanese literature and works of Japanese philosophy.[1]

Early life

Viglielmo was born in Palisades Park, New Jersey. He grew up in a small rural community in the Hudson Valley of New York State, he completed both his primary and secondary school education and began his college studies in that state. Being of draft age during World War II and knowing he would have to serve, he chose to volunteer, serving in the ASTRP (Army Specialized Training Reserve Program). He was eventually drafted in January 1945, undergoing basic training in Florida. The European phase of the war ended in May 1945 while he was in training, but the Pacific war was still raging.

Toward the end of his training Viglielmo responded to an appeal for enlisting in a Japanese language program being conducted under the auspices of the ASTP (the word “Reserve” no longer applied). He was sent to the University of Pennsylvania where he began an intensive nine-month course of study, almost exclusively in the spoken language. After the end of the war in August 1945, his training was then directed toward being an interpreter during the Occupation of Japan, and he served as such in the 720th Military Police Battalion in Tokyo from April to September 1946.

Academic career

In October 1946, after his military discharge, Viglielmo transferred to Harvard University to continue his study of Japanese in the then-Far Eastern Languages Department. He received his A.B. degree magna cum laude in June 1948. He was accepted into the Harvard graduate program for Fall 1948, but chose instead to go to Japan for a three-year position teaching English as a foreign language at Meiji Gakuin University in Tokyo.

In the summer of 1951 Viglielmo returned to Harvard, receiving his M.A. degree in June 1952. He then entered the Harvard Ph.D. program in Japanese Literature, completing his general examinations in June 1953. That same year he won a Ford Foundation Fellowship for two years of graduate study in Japan, studying both at Tokyo University and the Gakushūin University. His dissertation topic was “The Later Natsume Sōseki: His Art and Thought.”

At Gakushūin University, Viglielmo participated in a graduate seminar on Sōseki conducted by Sōseki biographer Komiya Toyotaka. In the spring of 1955 his Harvard teacher, Serge Elisséeff, asked Viglielmo if he would accept an appointment as a Harvard instructor in Japanese language and literature, beginning in Fall 1955. He taught at Harvard until June 1958, having completed his doctoral dissertation in December 1955 and having received his Ph.D. degree in March 1956. During the period from Fall 1958 until June 1960 he taught at International Christian University as well as Tokyo Women's Christian University and Tokyo University.

In September 1960, Viglielmo received an appointment as assistant professor at Princeton University, where he taught Japanese language and literature. In January 1965, he accepted an offer of an associate professorship in the then Department of Asian and Pacific Languages at the University of Hawai‘i. Viglielmo was soon promoted to full professor and taught at the University of Hawai‘i until his retirement at the end of August 2002.[2]

Academic works

Viglielmo's primary career focus was on modern Japanese literature, and he produced many studies of principal authors and their works, as well as translations. In 1971 Viglielmo translated the Sōseki novel Meian (Light and Darkness, 1916), which received high praise from Western literary critics such as Fredric Jameson and Susan Sontag. Two years earlier, in 1969, he translated a brace of essays, The Existence and Discovery of Beauty, which the first Japanese Nobel Prize recipient Kawabata Yasunari gave in the form of public lectures as a visiting professor at the University of Hawai‘i in May 1969.

From the late 1950s on, Viglielmo also developed an interest in modern Japanese philosophy, introducing to the Western world works by the two principal figures of the Kyoto school, Nishida Kitarō and Tanabe Hajime. Viglielmo was abled to visit Tanabe Hajime at his home in Spring of 1959. His first translation of Nishida, Zen no kenkyū (A Study of Good, 1911) in 1960 was considered instrumental in a deepening of East-West comparative philosophy.

Viglielmo's most sustained work in modern Japanese philosophy was a collaborative effort with David A. Dilworth and Agustin Jacinto Zavala, A Sourcebook for Modern Japanese Philosophy, in 1998. It was recognized as the first comprehensive study of its kind, with extensive selections from the work of seven major modern Japanese thinkers.

Viglielmo served as interpreter at the first International PEN meet in Tokyo in 1957. He formed friendships with the bundan (literary establishment), including Mishima Yukio, Kenzaburō Ōe, Sei Ito, Satō Haruo, and prominent critics such as Okuno Takeo and Saeki Shōichi.

Viglielmo was on the editorial staff of the Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. He was also the first editor of the Journal-Newsletter of the Association of Teachers of Japanese, which has since developed into the principal journal of scholars of the Japanese language and literature outside Japan. He also served as an Executive Committee member of that Association.

At the University of Hawai‘i he enjoyed teaching Meiji-Taishō (1868-1926) literature. He attended the first International Conference of Japanologists held in Kyoto in 1972.

Viglielmo also developed a close connection with the Japanese anti-nuclear group Gensuikin (Congress for the Abolition of Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs), and especially with the Nagasaki branch. He and his wife, Frances, were instrumental in facilitating the erection in 1990 of the Nagasaki Peace Bell in Honolulu, the funding for which came from the survivors of the Nagasaki atomic bombing and their relatives and friends. In the summer of 1998 Viglielmo and his wife were invited to Nagasaki to receive a Peace Prize in honor of their work in the anti-nuclear movement. In Honolulu they were granted the Peacemaker of the Year Award in 1988 by the Church of the Crossroads.

Bibliography

Books

Japanese Literature in the Meiji Era (translation and adaptation of Meiji bunkashi: bungei-hen, edited by Okazaki Yoshie). Tokyo: Obunsha, 1955.

A Study of Good (translation of Zen no kenkyū by Nishida Kitarō). Tokyo: Japanese National Commission for UNESCO (Japanese Government Printing Bureau), 1960.

The Existence and Discovery of Beauty (translation of Bi no sonzai to hakken by Kawabata Yasunari). Tokyo: Mainichi Shinbunsha, 1969.

Light and Darkness (translation of Meian by Natsume Sōseki, with Afterword). London: Peter Owen, 1971.

Art and Morality (translation with David A. Dilworth, of Geijutsu to dōtoku by Nishida Kitarō). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1973.

Philosophy as Metanoetics (translation, with Takeuchi Yoshinori and James Heisig, of Zangedō to shite no tetsugaku by Tanabe Hajime). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Intuition and Reflection in Self-Consciousness (translation, with Takeuchi Yoshinori and Joseph O’Leary, of Jikaku ni okeru chokkan to hansei by Nishida Kitarō). Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987.

Sourcebook for Modern Japanese Philosophy: Selected Documents. Translated and edited by David A. Dilworth and Valdo H. Viglielmo with Agustin Jacinto Zavala. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1998.

Light and Darkness: Natsume Sōseki's Meian—A New Translation By V. H. Viglielmo. CreateSpace, 2011.

Articles and Chapters in Books

“Meredeisu to Sōseki: shinrishōsetsu ni tsuite no ikkōsatsu” [Meredith and Sōseki: A Study in the Psychological Novel]. Tō 1:15 (1949), 30-33.

“Meiji bungaku ni oyoboshita Seiyō no eikyō” [The Influence of the West on Meiji Literature]. Meiji Gakuin ronsō 18 (1950), 57-64.

“Watakushi no mita Sōseki” [Sōseki as I See Him], Bungei (1954), 28-35.

“Sōsaku gappyō” [Critical Discussion of Seven New Works in Japanese Literature]. Gunzō 9:7 (1954), 267-288.

“The Joys of Life” (translation of Jinsei no kōfuku, three-act play, by Masamune Hakuchō). Japan Digest 6:10 (1954), 99-127.

“Watakushitachi no mita Nihon bungaku” [Japanese Literature as We See It]. Bungei 11:13 (1954), 16-30 (with Donald Keene, Nakamura Shin’ichirō, and Edward Seidensticker).

“Translations from Classical Korean Poetry.” Korean Survey 4:2 (1955), 8-9.

“Translations from Classical Korean Poetry.” Korean Survey 4:7 (1955), 8-9.

“Dōtoku ni okeru setchūshugi” [Eclecticism in Japanese Morality]. Gendai dōtoku kōza, Nihonjin no dōtokuteki shinsei 3 (1955), 190-195.

“Gaijin no me kara mita Nihon no igaku” [Japanese Medicine Seen through Foreign Eyes]. Gendai seirigaku geppō 2 (1955), 1-4.

“Scipione Amati's Account of the Date Masamune Embassy: A Bibliographical Note.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 19:1-2 (1956), 155-159 (with Robert H. Russell).

“A Translation of the Preface and the First Ten Chapters of Amati's Historia del Regno di Voxv....” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 20:3-4 (1957), 619-643.

“Memento Mori” (translation of an article with the same title by Tanabe Hajime). Philosophical Studies of Japan, Tokyo: Japanese National Commission for UNESCO 1 (1959), 1-12.

“Õgai to Sōseki” [Õgai and Sōseki]. Kōza: gendai rinri 9. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1959, 305-308.

“Japanese Language.” In Funk and Wagnalls Standard Reference Encyclopedia. New York: Standard Reference Works Publishing Company, 1962, Vol. 14, 5188-5190.

“Japanese Literature,” article in Funk and Wagnalls Standard Reference Encyclopedia (New York: Standard Reference Works Publishing Company, 1962), Vol. 14, 5190-5193.

“Haiku of Buson.” The Nassau Literary Magazine (March 1963), 16-19.

“An Introduction to the Later Novels of Natsume Sōseki.” Monumenta Nipponica 19:1-2 (1964), 1-36.

“A Few Comments on Translations from Modern Japanese Literature.” KBS Bulletin on Japanese Culture 87 (December 1967-January 1968), 10-14.

“On Donald Keene's Japanese Aesthetics.” Philosophy East & West 19:3 (1969), 317-322.

“Meian-ron” (A Study of Light and Darkness). Translated by Takeda Katsuhiko. In Koten to gendai [The Classics and the Present Age]. Tokyo: Shimizu Kōbundō, 1970, 241-271.

“Amerika ni okeru kindai Nihon bungaku kenkyü no dōkō” [Trends in the Study of Modern Japanese Literature in America]. Translated by Takeda Katsuhiko. In Kokubungaku kaishaku to kanshō. Issue titled Sekai bungaku no naka no Nihon bungaku [Japanese Literature within World Literature] 35:5 (1970), 50-67.

“Nishida Kitarō: The Early Years.” In Tradition and Modernization in Japanese Culture. Edited by Donald H. Shively. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971, 507-562.

“Yokomitsu Riichi ‘Jikan’ no güiteki kaishaku" [Yokomitsu Riichi's ‘Jikan’: An Allegorical Interpretation]. Translated by Takeda Katsuhiko. In Nihon kindai bungaku no hikakubungakuteki kenkyū [Comparative Literary Studies in Modern Japanese Literature] Tokyo: Shimizu Kōbundō, 1971, 353-371.

“Watakushi no mita Tanizaki” [Tanizaki as I See Him]. In Tanizaki Jun’ichirō kenkyū [Tanizaki Jun’ichirō Studies]. Edited by Ara Masahito. Tokyo: Yagi Shoten, 1972, 662-666.

“Akutagawa no bungaku” [The Literature of Akutagawa]. Translated by Takeda Katsuhiko. In Akutagawa bungaku—kaigai no hyōka [The Literature of Akutagawa: An Overseas Evaluation], edited by Yoshida Seiichi, Takeda Katsuhiko, and Tsuruta Kin’ya. Tokyo: Waseda Daigaku Shuppansha, 1972, 61-67.

“Virierumo no ‘Meian-ron’” [Viglielmo's Study of Light and Darkness]. Translated by Ara Masahito and Uematsu Midori. In Kokubungaku kaishaku to kyōzai no kenkyū 17:5 (1972), 204-220.

“Watakushi no mita Itō Sei” [Itö Sei as I See Him]. Translated by Takeda Katsuhiko. In Itō Sei kenkyū [Itö Sei Studies], edited by Hasegawa Izumi. Tokyo: Miyai Shoten, 1973, 124-130.

“Mishima and Brazil: A Study of Shiroari no su” [The Termite's Nest]. In Studies on Japanese Culture 1 (Tokyo: Japan PEN Club, 1973), 461-470.

“Mishima y Brasil: Un Estudio de Shiroari no su” (Spanish translation, by Guillermo Castillo Najero). Estudios Orientales 8:1 (1973), 1-18.

“Mizuumi shoron—minikui ashi” [A Brief Study of Mizuumi: The Ugly Feet]. Translated by Takeda Katsuhiko. In Kokubungaku shunjū 4 (1974), 2-7.

“The Concept of Nature in the Works of Natsume Sōseki.” The Eastern Buddhist 8:2 (1975), 143-153.

“Sōseki's Kokoro: A Descent into the Heart of Man.” In Approaches to the Japanese Modern Novel, edited by Kin’ya Tsuruta and Thomas E. Swann. Tokyo: Sophia University Press, 1976, 105-117.

“Yokomitsu Riichi's ‘Jikan’ (Time): An Allegorical Interpretation.” In Essays on Japanese Literature, edited by Takeda Katsuhiko. Tokyo: Waseda University Press, 1977, 105-117.

“Japanese Studies in the West: Past, Present, and Future.” In Proceedings Language, Thought, and Culture Symposium—1976, sponsored by Kansai University of Foreign Studies. Tokyo: Sanseidō, 1978, 209-220.

“Mishima bungaku sakuhinron” [A Discussion of Mishima's Literary Works] (with Takeda Katsuhiko). In

Kaikakusha 2 (1977), 76-87.

“Meian o chüshin ni—Eiyaku no shomondai” [With a Focus on Light and Darkness—Various Problems in Translation into English]. Hon’yaku no sekai 10 (1977), 19-27.

“Mizuumi-ron: nanto minikui ashi de aru koto ka” [A Study of The Lake: How Ugly Are the Feet!]. Translated by Imamura Tateo. In Kawabata Yasunari: The Contemporary Consciousness of Beauty, edited by Takeda Katsuhiko and Takahashi Shintarō. Tokyo: Meiji Shoin, 1978, 123-139.

“Amerika ni okeru kindai Nihon bungaku kenkyü no dōkō” [Trends in the Study of Modern Japanese Literature in America]. Translated by Takeda Katsuhiko. In Koten to gendai. edited by Takeda Katsuhiko. Tokyo: Shimizu Kōbundō, 1981, 41-84.

“Natsume Sōseki: ‘Hearing Things.’” In Approaches to the Modern Japanese Short Story, edited by Thomas E. Swann and Kin’ya Tsuruta. Tokyo: Waseda University Press, 1982, 243-254.

“Natsume Sōseki: ‘Ten Nights of Dreams.’” In Approaches to the Modern Japanese Short Story, edited by Thomas E. Swann and Kin’ya Tsuruta. Tokyo: Waseda University Press, 1982, 255-265.

Articles in Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1983): “Higuchi Ichiyō,” Vol. 3, 136; “Masamune Hakuchō,” Vol. 3, 122-123; “Nishida Kitarō,” Vol. 6, 14-15; “Tayama Katai,” Vol. 7, 358-359; “Zen no kenkyū,” Vol. 8, 376.

“The Aesthetic Interpretation of Life in The Tale of Genji.” In Analecta Husserliana 17, Phenomenology of Life in a Dialogue Between Chinese and Occidental Philosophy, edited by A-T. Tymieniecka. Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 1984, 347-359.

“The Epic Element in Japanese Literature.” In Analecta Husserliana 18, The Existential Coordinates of the Human Condition: Poetic—Epic—Tragic. Dordrecht: D. Reidel, 1984, 195-208.

“Nishida's Final Statement.” Monumenta Nipponica 43:3 (1988), 353-362.

“Watakushi wa naze han-tennōsei undō in sanka-shita no ka” [Why Have I Participated in the Anti-Emperor System Movement]. In Dokyumento: tennnō daigawari to no tatakai—‘Heisei hikokumin’ sengen [A Documentary Account of the Imperial Succession Struggle: The Declaration of the ‘Heisei Traitors’], edited by ‘Sokui-no-rei—Daijōsai’ ni Hantai Suru Kyōdō Kōdō. Tokyo: Kyūsekisha, 1991, 45-49.

“An Introduction to Tanabe Hajime's Existence, Love, and Praxis.” In Wandel zwischen den Welten: Festschrift für Johannes Laube, edited by Hannelore Eisenhofer-Halim. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2003, 781-797.

References

- "VALDO H. VIGLIELMO". Star Advertiser. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- "Reception Honoring Dr. Viglielmo" (PDF). Quarterly Newsletter of the Center for Japanese Studies, University of Hawaiëi at M‚noa. p. 2. Retrieved 28 February 2013.