V-1 flying bomb facilities

In order to carry out the planned V-1 "flying bomb" attacks on the United Kingdom, Germany built a number of military installations including launching sites and depots. Some of the installations were huge concrete fortifications.

| V-1 facilities | |

|---|---|

| Part of Nazi Germany | |

| locations in France and Germany | |

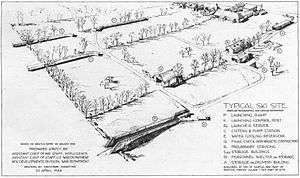

Diagram for Maisoncelle V-1 "ski site" | |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1943–1945 |

| Built by | Organisation Todt et al. |

| In use | World War II |

| Battles/wars | Operation Crossbow, Operation Aphrodite |

The Allies became aware of the sites at an early stage and carried out numerous bombing raids to destroy them before they came into use.

Production

The unpiloted aircraft was assembled at the KdF-Stadt[note 1] Volkswagenwerke (described as "the largest pressed-steel works in Germany"[1]) near Fallersleben, at Cham/Bruns Werke,[2]:40 and at the Mittelwerk, underground factory in central Germany. Production plants to modify several hundred standard V-1s to Reichenberg R-III manned aircraft were in the woods of Dannenburg and at Pulverhof, with air-launch trials at Lärz and Rechlin.[2]:133,135 Flight testing was performed by the Luftwaffe at Peenemünde West and, after the August 1943 Operation Hydra bombing, at Brüsterort.[2]:27 Launch crew training was at Zempin, and the headquarters for the operational unit, Flak-Regiment 155(W), was originally based at Saleux, near Amiens,[3][4]:173 but was subsequently moved c. December 1943 to a chateau near Creil ("FlakGruppeCreil"), with the unit's telephone relay station at Doullens.[5]

Other V-1 production-related sites included a Barth plant which used forced labor,[6] Buchenwald (V-1 parts),[7] and Allrich in the Harz.[8]

In addition to the storage and launching sites listed below, operational facilities included the airfields for Heinkel He 111 H-22 bombers which air-launched the V-1 from low altitude over the North Sea. The ten-day-long aircrew training was at Peenemünde, and the bases were in Gilze-Rijen, Holland, for launches through 15 September 1944, and in Venlo for launches after the first week in December. Aircrews were billeted five miles away at Grossenkneten for secrecy.[2]:126

Storage depots

To supply the V-1 flying bomb launch sites in the Calais region, construction began on several storage depots in August 1943. Sites at Biennais, Oisemont Neuville-au-Bois, and Saint-Martin-l'Hortier were not completed.[4] An RCAF Halifax pilot's logbook describes the target of his raids on "flying-bomb sites" on July 1, 4, and 5, 1944, as "Biennais #1", "Biennais #2," and "Biennais #3". This suggests that these storage sites were perhaps not completed because they were destroyed prior to completion.

The completed sites were:

- Domléger near Abbeville – bombed on June 14 and 16,[9] and on July 4, 1944.[10]

- Renescure near Saint-Omer – finished in November 1943, it was bombed by the USAAF on June 16, 1944 by 48 B-24s[11] and on July 2 by 21.[12][13]

- Sautricourt near Saint-Pol (bombed June 16, 1944).[11]

To serve the ten launch sites planned for Normandy, a depot was constructed at[4] Beauvais. It was bombed June 14, 15 and 16, 1944.[11]

A depot to serve Cherbourg launches was built near[4] Valognes. By February/March 1944, a plan for three new underground V-1 storage sites was put into effect.[4] The Nucourt limestone cave complex between Pontoise and Gisors was bombed on June 22, 1944 [11] with 298 V-1s buried or severely damaged.[14]One in the Rilly-la-Montagne railway tunnel was attacked by the British with Tallboy earthquake bombs on July 31, collapsing both ends of the tunnel.[15] The Saint-Leu-d'Esserent mushroom caves was the largest of the underground V-1 sites. It was attacked by No. 617 Squadron RAF with Tallboys on July 4.[14][15]

A larger "Heavy Crossbow"[16] bunker was built at Siracourt, between Calais and the river Somme,[17] as a V-1 storage depot.[18]

RAF records refer to flying-bomb stores at Bois de Cassan (bombed August 2–4, 1944),[19] Forêt de Nieppe (bombed July 28, 29, 31,[10][15] August 3,4,[19] 5, 6,[10][19] 1944 and Trossy St. Maximin (bombed August 3–4, 1944[19][20][21])

V-1 launch sequence

- Final Assembly: After moving the V-1 from the storage area, the wings were slid/bolted over/to the tubular spar.[2]:35

- Final Checkout: In the non-magnetic building, "compass swinging" was completed by hanging the V-1 and pointing it toward the target. The missile's external casing of 16-gauge sheet steel was beaten with a mallet until its magnetic field was suitably aligned. The automatic pilot was set with the flight altitude input (300–2500 metres) to the barometric (aneroid) height control and with the range set within the air log (journey computer).[2]:29,35

- Hoisting: The V-1 was delivered to the launching ramp via a wooden handling trolley on rails.[2]:34 A wooden lifting gantry on rails was connected to the V-1 lifting lug to hoist and move it onto the launching spot at the lower end of the launching ramp.[2]:30,34,35

- Fueling and Charging: Via the tank filler cap, 1,133 lbs (140 gallons) of petrol (German: B-Stoff) were added (later longer-range models held more). The twin spherical iron air bottles were charged with 900 psi air to power the automatic pilot (Steuergerät). Air at 90 psi powered the pneumatic servo-motors for the elevators and rudder.[2]:31,37

- Catapult setup: The starter trolley with the hydrogen peroxide (German: T-Stoff) and catalyst (potassium permanganate granules, Z-stoff) was connected to provide steam to the ramp's firing tube, and the steam piston was placed into the firing tube with the piston's launching lug connected to the V-1.[2]:30,33,35,64d

- V-1 startup: While the steam-generating trolley was being connected, the Argus As 109-014 Ofenrohr pulsejet engine was started.[2]:32,35

- Launch

- Post-launch: The steam piston, having separated from the V-1 at the end of the ramp during launch, was collected for re-use (the site nominally had only two pistons). Personnel in rubber boots and protective clothing used a catwalk along the ramp and washed the launching rail with brooms.[2]:32,35

V-1 launching sites

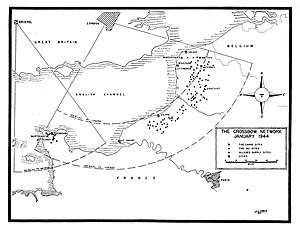

V-1 launching sites in France were located in nine general areas – four of which had the ramps aligned toward London, and the remainder toward Brighton, Dover, Newhaven, Hastings, Southampton, Manchester, Portsmouth, Bristol, and Plymouth. The sites on the Cherbourg peninsula targeting Bristol and Plymouth were captured before being used, and eventually launching ramps were moved to Holland to target Antwerp (first launched on 3 March 1945 from Delft).[2]:48,80,82,100

Initially the V-1 launching sites had storage buildings that were curved at the end to protect the contents against damage from air attacks. On aerial reconnaissance pictures these storage from above looked like snow skis ("ski sites"). An October 28, 1943 intelligence report regarding construction at Bois Carré near Yvrench[22] prompted No. 170 Squadron RAF reconnaissance sortie E/463 on November 3 which detected "ski-shaped buildings 240-270 feet long."[23] By November 1943, 72 of the ski sites had been located by Allied reconnaissance,[24] and Operation Crossbow began bombing the original ski sites on December 5, 1943. Nazi Germany subsequently began constructing modified sites with limited structures that could be completed quickly, as necessary. This also allowed the modified sites to be quickly repaired after bombing. However, the work to complete a modified site before launching allowed the Allied photographic interpreters to predict on June 11, 1944 that the V-1 attacks would begin within 48 hours, and the first attacks began on June 13.[24]

Allied attacks

| Site | "Noball" number |

Bombing date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abbeville/Amiens | December 22/23, 1943 | ||

| Abbeville/Amiens | August 28, 1944 | ||

| Abbeville (Flixecourt) | December 16/17, 1943 | ||

| Abbeville (Gorenflos) | December 23, 1943 | ||

| Abbeville (Gorenflos) | March 18, 1944[26] | ||

| Abbeville (Gorenflos) | April 9, 1944[27] | ||

| Abbeville (Gorenflos) | April 10, 1944 | ||

| Abbeville (Gorenflos) | June 9, 1944[10] | ||

| Abbeville (Tilley-le-Haut) | December 16/17, 1943 | ||

| Acque | July 19, 1944 | ||

| Ailly-le-Haut-Clocher[2]:49 | 27 | December 22/23, 1943 | |

| Ailly-le-Haut-Clocher | 27 | January 14/15, 1944[29] | |

| Beauvais | April 24 & 25, 1944 | ||

| Beauvais | May 16, 1944 | The Normandy V-1 storage site at Beauvais was bombed.[4] | |

| Beauvais | June 11, 1944 | ||

| Beauvais | June 14, 15, & 16, 1944 | ||

| Belloy-Sur-Somme | July 6, 1944 | ||

| Bois Carré near Yvrench | February 10, 1944 | ||

| Bonneton le Faubourg ski site | December 22/23, 1943 | ||

| Bonneton le Faubourg ski site | January 14/15, 1944[29] | ||

| Bristillerie | December 22/23, 1943 | ||

| Bristillerie | January 4/5, 1944 | ||

| Bristillerie | January 14/15, 1944[29] | ||

| Bouillancourt | April 13, 1944 | ||

| Creil | July 2, 1944 | ||

| Bois de la Justice | 74 | February 28, 1944 | |

| Bois de la Justice | 74 | March 13, 1944 | |

| Drionville | 50 | December 24, 1943 | |

| Grand Parc | 107 | January 14, 1944 | |

| Grand Parc | 107 | January 21, 1944 | |

| Herbouville | January 27/28, 1944 | ||

| Herbouville | January 29/30, 1944 | ||

| La Briqueterie & Val-des-Joncs | August 2, 1944 | ||

| Laloge Au Pain | July 8, 1944 | ||

| Ligercourt [sic] | April 16, 1944 | ||

| Ligescourt | December 5, 1943 | ||

| Lottinghen | March 13, 1944 | ||

| Maisoncelle[24][33] | June 1, 1944[10] | ||

| Oisemont Neuville-au-Bois | June 20, 1944[10] | ||

| Oisemont | June 21, 1944 | ||

| Oisemont | June 23, 1944[10] | ||

| Oisemont | June 30, 1944 | ||

| Oisemont | July 1, 1944[10] | ||

| Söttevast | February 29/March 1, 1944 | ||

| Söttevast | March 3/4, 1944 | ||

| Söttevast | May 5, 1944[10] | ||

| Saint-Martin-l'Hortier | June 17, 1944[10] | ||

| Saint-Martin-l'Hortier | June 21, 1944 | ||

| Saint-Martin-l'Hortier | July 1, 1944 |

Notes

- A different source puts the Fallersleben KdF-Stadt V-1 factory in Wolfsburg; Fallersleben become a district of Wolfsburg in 1972. The Allies also bombed the Opel plant at Russelsheim in the incorrect belief that it was a V-1 plant.

References

- Citations

- "Chapter 11 — Flying Bombs and Rockets". New Zealanders With The Royal Air Force (Vol. II): Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington, New Zealand: R. E. Owen. 1956. p. 333. Retrieved February 16, 2019 – via New Zealand Electronic Text Collection.

- Cooksley, Peter G. (1979). Flying Bomb. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-68416-284-3.

- Holm, Michael (2006). "Flak-Regiment 155 (W)". The Luftwaffe, 1933-45. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- Henshall, Philip (1985). Hitler's Rocket Sites. New York: St Martin's Press. pp. 143, 152, 187, 209. ISBN 978-0-31238-822-5.

- Jones (1978), p. 300e, 352, 373.

- Aroneanu, Eugène; Whissen, Thomas (1996). Inside the Concentration Camps. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-275-95446-8. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- "David P. Boder Interviews Ludwig Hamburger; August 26, 1946; Genève, Switzerland". Voices of the Holocaust. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "David P. Boder Interviews Jacob Schwarzfitter; August 31, 1946; Tradate, Italy". Voices of the Holocaust. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "The 446th Bomb Group (H) Missions". Web-birds.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- "466 Squadron Missions". Halifaxlv827.co.uk. Archived from the original on January 13, 2009. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- "Combat Chronology of the US Army Air Forces: June 1944". The United States Army Air Forces in World War II. Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Combat Chronology of the US Army Air Forces: July 1944". The United States Army Air Forces in World War II. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Missions Flown by the 453rd BG". 453rd Bomb Group (H). Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- Jones (1978), p. 246.

- "Bomber Command Campaign Diary: July 1944". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Investigations of the "Heavy Crossbow" installations in Northern France". The Papers of Lord Duncan-Sandys. Churchill Archives Centre. February 1945. Retrieved May 9, 2007.

- Ordway, Frederick I., III; Sharpe, Mitchell R. (1979). The Rocket Team. Apogee Books Space Series 36. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-69001-656-7.

- Irving, David (1964). The Mare's Nest. London: William Kimber and Co. pp. 168, 220, 245, 246.

- "Bomber Command Campaign Diary: August 1944". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. Archived from the original on June 7, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- Stooke, Gordon. "What Happened To Your 460 Sqd. Lancaster?". 460 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force, Bomber Command. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Mission Details, 4 August 1944". 156 Squadron RAF. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- Jones (1978), p. 300e.

- Jones (1978), p. 360.

- Gurney, Gene (Major, USAF) (1962). The War in the Air: a pictorial history of World War II Air Forces in combat. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 184.

- "Bomber Command Campaign Diary: December 1943". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- Baugher, Joseph F. "1941 USAAF Serial Numbers (41-24340 – 41-30847)". American Bombers. Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

Other Baugher webpages cited in this article:- "1942 USAAF Serial Numbers (42-50027 – 42-57212)". American Bombers. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "1942 USAAF Serial Numbers (42-91974 – 42-110188)". American Bombers. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "No. 438 Squadron" (PDF). Manitoba Military Aviation Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 14, 2012.

- "Comrades Killed in Action". 457th Bomb Group Association. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Bomber Command Campaign Diary: January 1944". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. Archived from the original on June 11, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Code Named "Aphrodite"". Edenbridge in the Past. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "387th Bombardment Group (Medium)". 387bg.com. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Combat Chronology of the US Army Air Forces: December 1943". The United States Army Air Forces in World War II. Archived from the original on October 7, 2006. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- Bauer, Eddy (1966) [1972]. Illustrated World War II Encyclopedia. 15. H. S. Stuttman Inc. pp. 2059, 2068. ISBN 0-87475-520-4.

- Bibliography

- Jones, R. V. (1978). Most Secret War. London, UK: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-89746-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Boyd. "301st Bomb Group Mission Summary of the 32nd, 352nd, 353rd and 419th Bomb Squadrons". 32nd Bomb Squadron, 1942-1945. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "2nd Lt. Donald A. Jones". 100th Bomb Group (Heavy): The Bloody Hundredth. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- "Combat Mission No. 331, 7 March 1945" (PDF). 'Hell's Angels': 303rd Bombardment Group (Heavy). Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Missions 1943–1945". 384th Bomb Group (Heavy). Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- "Missions". 401st Bombardment Group (H) Association. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "The Missions". 447th Bomb Group. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2009.

- "June 1944 Missions". 461st Bombardment Group (H). Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Our Missions". The 464th Bomb Group Association. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Combat Missions". 487th Bomb Group (H). Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- Smith, Michael E. "596th Bomb Squadron History, 1945" (PDF). Martin B-26 Marauder Men. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2009. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- "Bomber Command Campaign Diary". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- McKillop, Jack. "Combat Chronology of the USAAF". USAAF.net. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved May 25, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to V-1. |