Usual interstitial pneumonia

Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) is a form of lung disease characterized by progressive scarring of both lungs.[1] The scarring (fibrosis) involves the supporting framework (interstitium) of the lung. UIP is thus classified as a form of interstitial lung disease.

| Usual interstitial pneumonia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Usual interstitial pneumonitis (UIP) |

.jpg) | |

| CT scan of a patient with UIP. There is interstitial thickening, architectural distortion, honeycombing and bronchiectasis. | |

| Specialty | Respirology |

Terminology

The term "usual" refers to the fact that UIP is the most common form of interstitial fibrosis. "Pneumonia" indicates "lung abnormality", which includes fibrosis and inflammation. A term previously used for UIP in the British literature is cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis (CFA), a term that has fallen out of favor since the basic underlying pathology is now thought to be fibrosis, not inflammation. The term usual interstitial pneumonitis (UIP) has also often been used, but again, the -itis part of that name may overemphasize inflammation.

Signs and symptoms

The typical symptoms of UIP are progressive shortness of breath and cough for a period of months. In some patients, UIP is diagnosed only when a more acute disease supervenes and brings the patient to medical attention.

Causes

The cause of the scarring in UIP may be known (less commonly) or unknown (more commonly). Since the medical term for conditions of unknown cause is "idiopathic", the clinical term for UIP of unknown cause is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).[2] Examples of known causes of UIP include connective tissue diseases (primarily rheumatoid arthritis), drug toxicity, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, asbestosis and Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome.[2]

Diagnosis

-CT_scan.jpg)

UIP may be diagnosed by a radiologist using computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, or by a pathologist using tissue obtained by a lung biopsy.

Radiology

Radiologically, the main feature required for a confident diagnosis of UIP is honeycomb change in the periphery and the lower portions (bases) of the lungs.[3]

On high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), the following categories, depending on imaging findings, have been recommended by a collaborative effort by the American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and the Latin American Thoracic Society:[4]

- UIP pattern:[4]

- Honeycombing, with or without peripheral traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis

- Predominantly subpleural and basal

- Often heterogenous distribution, being occasionally diffuse, and may be asymmetrical

There may be superimposed CT features such as mild ground-glass opacity, reticular pattern and pulmonary ossification.

- Probable UIP pattern:[4]

- Predominantly subpleural and basal

- Often hererogenous distribution

- Reticular pattern with peripheral traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis

- There may be mild ground-glass opacity

- Indeterminate for UIP:[4]

- Predominantly subpleural and basal

- Subtle reticular pattern

- May have mild ground-glass opacity or distortion (“early UIP pattern”)

- Findings suggestive of another diagnosis, including:[4]

- Other predominant distribution:

- Peribronchovascular

- Perilymphatic

- Upper or mid-lung

- Cysts

- Marked mosaic pattern

- Predominant ground-glass opacity

- Profuse micronodules

- Nodules, especially centrilobular

- Consolidation

- Pleural plaques (indicating asbestosis)

- Dilated esophagus (indicating connective tissue disease)

- Distal clavicular erosions (indicating rheumatoid arthritis)

- Extensive lymph node enlargement

- Pleural effusion

- Pleural thickening (indicating connective tissue disease/drugs)

Histology

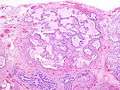

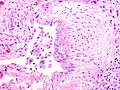

The histologic hallmarks of UIP, as seen in lung tissue under a microscope by a pathologist, are interstitial fibrosis in a "patchwork pattern", honeycomb change and fibroblast foci (see images below).[5]

- Pathological findings in usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP)

Appearance of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) in a surgical lung biopsy at low magnification. The tissue is stained with hematoxylin (purple dye) and eosin (pink dye) to make it visible. The pink areas in this picture represent lung fibrosis (collagen stains pink). Note the "patchwork" (quilt-like) pattern of the fibrosis.

Appearance of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) in a surgical lung biopsy at low magnification. The tissue is stained with hematoxylin (purple dye) and eosin (pink dye) to make it visible. The pink areas in this picture represent lung fibrosis (collagen stains pink). Note the "patchwork" (quilt-like) pattern of the fibrosis. Appearance of honeycomb change in a surgical lung biopsy at low magnification. The dilated spaces seen here are filled with mucin. Hematoxylin-eosin stain, low magnification.

Appearance of honeycomb change in a surgical lung biopsy at low magnification. The dilated spaces seen here are filled with mucin. Hematoxylin-eosin stain, low magnification. A fibroblast focus in a surgical lung biopsy of UIP. Hematoxylin-eosin stain, high magnification. The white space to the left is an airspace. The pale area to the right is a fibroblast focus. It is an area of active fibroblast proliferation within the interstitium of the lung.

A fibroblast focus in a surgical lung biopsy of UIP. Hematoxylin-eosin stain, high magnification. The white space to the left is an airspace. The pale area to the right is a fibroblast focus. It is an area of active fibroblast proliferation within the interstitium of the lung.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes other types of lung disease that cause similar symptoms and show similar abnormalities on chest radiographs. Some of these diseases cause fibrosis, scarring or honeycomb change. The most common considerations include:

- chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- non-specific interstitial pneumonia

- sarcoidosis

- pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- asbestosis [6]

Management

Oxygen therapy may assist with daily living. In case of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, certain medications like nintedanib and pirfenidone can help slow the progression.[7] Lastly, lung transplants may help.

Prognosis

Regardless of cause, UIP is relentlessly progressive, usually leading to respiratory failure and death without a lung transplant. Some patients do well for a prolonged period of time, but then deteriorate rapidly because of a superimposed acute illness (so-called "accelerated UIP"). The outlook for long-term survival is poor. In most studies, the median survival is 3 to 4 years. Patients with UIP in the setting of rheumatoid arthritis have a slightly better prognosis than UIP without a known cause (IPF).

History

UIP, as a term, first appeared in the pathology literature. It was coined by Averill Abraham Liebow.[8]

See also

References

- Travis WD, King TE, Bateman ED, et al. (2002). "ATS/ERS international multidisciplinary consensus classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. General principles and recommendations". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 165 (5): 277–304. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01. PMID 11790668.

- Wuyts, W. A.; Cavazza, A.; Rossi, G.; Bonella, F.; Sverzellati, N.; Spagnolo, P. (2014). "Differential diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia: when is it truly idiopathic?". European Respiratory Review. 23 (133): 308–319. doi:10.1183/09059180.00004914. ISSN 0905-9180.

- Sumikawa H, et al. (2008). "Computed tomography findings in pathological usual interstitial pneumonia: relationship to survival". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 177 (4): 433–439. doi:10.1164/rccm.200611-1696OC. PMID 17975197.

- Raghu, Ganesh; Remy-Jardin, Martine; Myers, Jeffrey L.; Richeldi, Luca; Ryerson, Christopher J.; Lederer, David J.; Behr, Juergen; Cottin, Vincent; Danoff, Sonye K.; Morell, Ferran; Flaherty, Kevin R.; Wells, Athol; Martinez, Fernando J.; Azuma, Arata; Bice, Thomas J.; Bouros, Demosthenes; Brown, Kevin K.; Collard, Harold R.; Duggal, Abhijit; Galvin, Liam; Inoue, Yoshikazu; Jenkins, R. Gisli; Johkoh, Takeshi; Kazerooni, Ella A.; Kitaichi, Masanori; Knight, Shandra L.; Mansour, George; Nicholson, Andrew G.; Pipavath, Sudhakar N. J.; Buendía-Roldán, Ivette; Selman, Moisés; Travis, William D.; Walsh, Simon L. F.; Wilson, Kevin C. (2018). "Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 198 (5): e44–e68. doi:10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST. ISSN 1073-449X.

- Katzenstein AL, Mukhopadhyay S, Myers JL (2008). "Diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia and distinction from other fibrosing interstitial lung diseases". Human Pathology. 39 (9): 1275–1294. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2008.05.009. PMID 18706349.

- Leslie, Kevin O; Wick, Mark R. (2005). Practical pulmonary pathology: a diagnostic approach. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-06631-0. OCLC 156861539.

- Reviewed and approved by the American Lung Association Scientific and Medical Editorial Review Panel. Last reviewed February 5, 2018.

- Averill Abraham Liebow at Who Named It?