Urvashi

Urvaśī (Sanskrit: उर्वशी, lit. 'she who controls hearts')[lower-alpha 1] is an apsara in Hindu legend. Monier Monier-Williams proposes a different etymology in which the name means 'widely pervasive' and suggests that in its first appearances in Vedic texts it is a name for the dawn goddess. She was a celestial maiden in Indra's court and was considered the most beautiful of all the Apsaras.

| Urvashi | |

|---|---|

The most beautiful Apsara | |

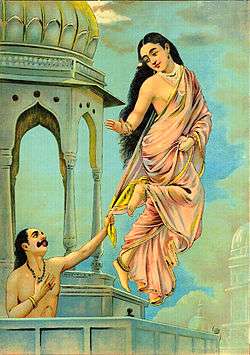

Urvashi and Pururavas painted by Raja Ravi Varma | |

| Affiliation | Apsara |

| Personal information | |

| Children | Rishyasringa from Vibhandaka Ayu and Amavasu from king Pururavas |

She is the mother of Rishyasringa, the great saint of the Ramayana era of ancient India from Vibhandaka, who later played crucial role in birth of Rama and was married to Shanta, the elder sister of Rama.

She became the wife of king Pururavas (Purūrávas, from purū+rávas "crying much or loudly"), an ancient chief of the lunar race. ShBr 11.5.1, and treated in Kalidasa's drama Vikramōrvaśīyam.

She is perennially youthful and infinitely charming but always elusive.[1] She is a source as much of delight as of dolour.[2]

Birth

There are many legends about the birth of Urvaśī but the following one is most prevalent.

Once the revered sages Nara-narayana were meditating in the holy shrine of Badrinath Temple situated in the Himalayas. Indra, the king of the Gods, did not want the sage to acquire divine powers through meditation and sent two apsaras to distract him. The sage struck his thigh and created a woman so beautiful that Indra’s apsaras were left matchless. This was Urvaśī, named from ur, the Sanskrit word for thigh. After his meditation was complete the sage gifted Urvaśī to Indra, and she occupied the place of pride in Indra’s court.

Urvaśī's Curse

She is also mentioned in the Mahabharata, as the celestial dancer of Indra's palace. When Arjuna had come for obtaining weapons from his father, his eyes fall upon Urvaśī. Indra seeing this sent Chitrasena to address Urvasi to wait upon Arjuna. Hearing virtues of Arjuna, Urvasi was filled with desire. At twilight, she reached Arjuna's abode. As soon as Arjuna saw that beauty at night in her room in beautiful attire, from fear, respect, modesty and shyness he saluted her with closed eyes. She told Arjuna everything and also of her heart desire. But Arjuna refused, as considering her to his superior of old. He also mentioned that she was like his mother because of her past marriage to Pururavas.

.jpg)

In wrath she cursed Arjuna of destitute of manhood and scorned as a eunuch for a year. This curse helped Arjuna during his Agyatvās.[3]

Notes

- "Ur" means heart and "vash" means to control

References

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Urvashi |

- George (ed.), K.M. (1992). Modern Indian Literature, an Anthology. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-7201-324-0.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- George (ed.), K.M. (1992). Modern Indian Literature, an Anthology. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-7201-324-0.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- https://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m03/m03046.htm

Bibliography

- Dowson, John. A Dictionary of Hindu Mythology & Religion.

- “Urvaśī and the Swan Maidens: The Runaway Wife.” In Search of the Swan Maiden: A Narrative on Folklore and Gender, by Barbara Fass Leavy, NYU Press, NEW YORK; LONDON, 1994, pp. 33–63. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg995.5. Accessed 23 Apr. 2020.

- Gaur, R. C. “The Legend of Purūravas and Urvaśī: An Interpretation.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, no. 2, 1974, pp. 142–152. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25203565. Accessed 27 Apr. 2020.

- Wright, J. C. “Purūravas and Urvaśī.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, vol. 30, no. 3, 1967, pp. 526–547. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/612386. Accessed 27 Apr. 2020.

- "‘Cupid, Psyche, and the “Sun-Frog”’, Custom and Myth: (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1884)." In The Edinburgh Critical Edition of the Selected Writings of Andrew Lang, Volume 1: Anthropology, Fairy Tale, Folklore, The Origins of Religion, Psychical Research, edited by Teverson Andrew, Warwick Alexandra, and Wilson Leigh, 66-78. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015. Accessed June 6, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt16r0jdk.9.