Urraca of León

Urraca (April 1079 – 8 March 1126) called the Reckless (la Temeraria),[1] was Queen of León, Castile, and Galicia from 1109 until her death. She claimed the imperial title as suo jure Empress of All Spain[2] and Empress of All Galicia.[3]

| Urraca | |

|---|---|

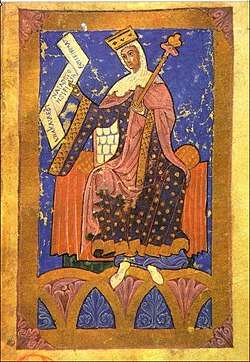

13-century miniature of Queen Urraca presiding the Court from Tumbo A codex Santiago de Compostela Cathedral | |

| Queen of León, Castile, and Galicia Empress of Spain | |

| Reign | 1109–1126 |

| Coronation | 1108 |

| Predecessor | Alfonso VI |

| Successor | Alfonso VII |

| Born | April 1079 Burgos |

| Died | 8 March 1126 (aged 46) Saldaña on the Río Carrión in Castilla |

| Burial | Basilica of San Isidoro |

| Spouse | Raymond of Burgundy Alfonso I of Aragon and Navarre (annulled) |

| Issue | Sancha Raimúndez Alfonso VII of León and Castile Fernando Pérez Furtado (illegitimate) Elvira Pérez de Lara (illegitimate) |

| House | Jiménez |

| Father | Alfonso VI of León and Castile |

| Mother | Constance of Burgundy |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Life

Early years

Born in Burgos, Urraca was the eldest and only surviving child of Alfonso VI of León with his second wife Constance of Burgundy;[4] for this, she was heir presumptive of the Kingdoms of Castile and León until 1107, when her father recognized his illegitimate son Sancho as his heir.

Urraca’s place in the line of succession made her the focus of dynastic politics, and she became a child bride at age eight (1087) to Raymond of Burgundy, a mercenary adventurer.[5] Urraca's marriage to Raymond was part of Alfonso VI's diplomatic strategy to attract cross-Pyrenees alliances. Author Bernard F. Reilly suggests that, rather than a betrothal, the eight-year-old Urraca was fully wedded to Raymond of Burgundy, as he almost immediately appears in protocol documents as Alfonso VI's son-in-law, a distinction that would not have been made without the marriage. Reilly doubts that the marriage was consummated until Urraca was 13, as she was placed under the protective guardianship of a trusted magnate. Her pregnancy and stillbirth at age 14 suggest that the marriage was indeed consummated when she was 13 or 14 years old.

In addition to this stillborn child, Urraca gave birth to two more children by Raymond: a daughter, Sancha Raimúndez (born after 11 November 1095 and before 1102) and a son, Alfonso Raimúndez, who would become Alfonso VII (born 1 March 1105).[6] Raymond died in 1107, leaving Urraca a widow with two small children.

Urraca became again an heir presumptive after the death of her half-brother Sancho at the Battle of Uclés in 1108. Alfonso VI reunited the nobles of the Kingdom in Toledo and announced that his widowed daughter was the chosen one to succeeded him. The nobles agreed with the royal designation but demanded that Urraca should marry again. Several candidates for the hand of the heiress to the thrones of León and Castile appeared immediately, including counts Gómez González and Pedro González de Lara. Alfonso VI feared that the rivalries between Castilian and Leonese nobles would be increased if she married any of these suitors and decided that his daughter should wed Alfonso I of Aragon, known as the Battler, opening the opportunity for uniting León-Castile with Aragon.

Reign

Marriage negotiations were still underway when Alfonso VI died on 29 June/1 July 1109 and Urraca became queen. Many of Alfonso VI’s advisers and leading magnates in the kingdom formed a “quiet opposition” to the marriage of the queen to the King of Aragon. According to Bernard F. Reilly, these magnates feared the influence the King of Aragon might attempt to wield over Urraca and over Leonese politics.

Urraca protested against the marriage but honoured her late father's wishes (and the Royal Council's advice) and continued with the marriage negotiations, though she and her father’s closest advisers were growing weary of Alfonso I's demands. Despite the advisers' opposition, the prospect of Count Henry of Portugal filling any power vacuum led them to go ahead with the marriage which took place in early October 1109 at the Castle of Monzón de Campos, with the major of the fortress, Pedro Ansúrez, acting as godfather of the wedding. As events unfolded, these advisers underestimated Urraca's political prowess, and later advised her to end the marriage.

The marriage of Urraca and Alfonso I almost immediately sparked rebellions in Galicia[7] and scheming by her illegitimate half-sister Theresa and brother-in-law Henry, the Countess and Count of Portugal. Also, they believed that the new marriage of Urraca could put in jeopardy the rights of the son of her first marriage, Alfonso Raimúndez. One of the first acts of the new spouses was to sign a pact under which the monarchs granted to each other soberana potestas over the other's kingdom, declaring heir of both their future children, and in the case that the union was childless, the surviving spouse would succeed the other one in the throne. From the start, the Galician faction was divided in two tendencies: one headed by Diego Gelmírez, Archbishop of Santiago de Compostela (who defended the position of Alfonso Raimúndez as Urraca's successor) and another led by Count Pedro Fróilaz de Traba, tutor of the young prince (who was inclined to the complete independence of Galicia under the rule of Alfonso).

.jpg)

A third group of opposition to the royal marriage was at the court and was headed by Count Gómez González, whose motivation against Urraca and Alfonso I of Aragon could have been his fear of losing power, a sensation soon confirmed when Alfonso I appointed Aragonese and Navarrese nobles for important public posts and as holders of fortresses.

From Galicia, the count of Traba began the first aggressive movement against the monarchs reclaiming the hereditary rights of Alfonso Raimúndez. In response to the Galician rebellion, Alfonso I of Aragon marched with his army to Galicia and in 1110, reestablished the order there after defeating the local troops in Monterroso Castle.

The Galician rebellion against the royal power was only the beginning of a series of political and military conflicts which, with the complete opposite personalities of Urraca and Alfonso I and their mutual dislike, gave rise to a continuous civil war in the Hispanic kingdoms over the following years. Urraca did not share the governance of her realms with her husband.[8]

As their relationship soured, Urraca accused Alfonso of physical abuse, and by May 1110 she separated from Alfonso. In addition to her objections to Alfonso's handling of rebels, the couple had a falling-out over his execution of one of the rebels who had surrendered to the queen, to whom the queen was inclined to be merciful. Additionally, as Urraca was married to someone many in the kingdom objected to, the queen's son and heir became a rallying point for opponents to the marriage.

Estrangement between husband and wife escalated from discrete and simmering hostilities into open armed warfare between the Leonese-Castilians and the Aragonese. An alliance between Alfonso of Aragon and Henry of Portugal culminated in the 1111 Battle of Candespina in which Urraca's lover and chief supporter Gómez González was killed. He was soon replaced in both roles by another count, Pedro González de Lara, who took up the fight and would father at least two further children by Urraca: a daughter, Elvira Pérez de Lara (c.1112-1174), who would wed twice, first to García Pérez de Traba, lord of Trastámara and son of Pedro Fróilaz de Traba, then to count Beltrán de Risnel, and a son, Fernando Pérez Hurtado (c.1114-1156). By the fall of 1112 a truce was brokered between Urraca and Alfonso with their marriage annulled. Though Urraca recovered Asturias, Leon, and Galicia, Alfonso occupied a significant portion of Castile (where Urraca enjoyed large support), while her half-sister Theresa and her husband Count Henry of Portugal occupied Zamora and Extremadura. Recovering these regions and expanding into Muslim lands would occupy much of Urraca's foreign policy. Despite the annulment of their marriage (on the grounds of consanguinity), Alfonso continued his efforts for political control.[9] While Urraca was engaged in this battle, she also had to contend with the schemes of her sister, who promoted a plan to replace the queen by her son. This particular incident, ended in a compromise between the two sisters where Theresa was granted a vast territory in Leon in exchange for agreeing that she was Urraca's vassal.[9]

According to author Bernard F. Reilly, the measure of success for Urraca’s rule was her ability to restore and protect the integrity of her inheritance – that is, the kingdom of her father – and transmit that inheritance in full to her own heir. Policies and events pursued by Alfonso VI – namely legitimizing her brother and thereby providing an opportunity for her illegitimate half-sister to claim a portion of the patrimony, as well as the forced marriage with Alfonso I of Aragon – contributed in large part to the challenges Urraca faced upon her succession. Additionally, the circumstance of Urraca’s gender added a distinctive role-reversal dimension to diplomacy and politics, which Urraca used to her advantage.

Character

Urraca is characterized in the Historia Compostelana as prudent, modest, and with good sense. According to Reilly, the Historia Compostelana also attributes her "failings" to her gender, "the weakness and changeability of women, feminine perversity, and calls her a Jezebel" for her liaisons with her leading magnates, with at least one relationship producing an illegitimate son. These observations were hardly neutral or dispassionate, according to Reilly, who wrote: "[T]here is no question that the queen is in control, perhaps all too much in control, of events." Urraca's use of sex in politics should be viewed more as a strategy that provided the queen with allies but without any masters.

Death and legacy

As queen, Urraca rose to the challenges presented to her and her solutions were pragmatic ones, according to Reilly, and laid the foundation for the reign of her son Alfonso VII, who in spite of the opposition of Urraca's lover Pedro González de Lara succeeded to the throne of a kingdom whole and at peace at Urraca’s death in 1126. The queen's reign also served as the legal precedent for the reigns of future queens.[10]

Notes

- "Urraca, first queen of Castile. A battered woman", elartedelahistoria.com

- The actual title in the text is Queen of Spain (Ispanie regina), a title analogous to that of Imperator totius Hispaniae, according to Bernard F. Reilly

- La Reina Urraca (in Spanish)

- Hereford Brooke George, Genealogical Tables Illustrative of Modern History, (Oxford Clarendon Press, 1875), table XXXVI

- Klapisch-Zuber, Christine; A History of Women: Book II Silences of the Middle Ages, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England. 1992, 2000 (5th printing). Chapter 6, "Women in the Fifth to the Tenth Century" by Suzanne Fonay Wemple, pg 74. Spanish law allowed women to inherit land and title. According to Wemple, Visigothic women of Spain and Aquitaine could inherit land and title and manage it independently of their husbands, and dispose of it as they saw fit if they had no heirs, and represent themselves in court, appear as witnesses (over the age of 14), and arrange their own marriages over the age of twenty.

- Hereford Brooke George, Genealogical Tables Illustrative of Modern History, (Oxford Clarendon Press, 1875), table XXVIII

- Galician nobles feared their influence in the kingdom of Leon would be significantly lessened in favor of Alfonso I and his Aragonese nobles. One first factions was formed by the French clergy, who had been reinforced by the first marriage of Urraca and now feared losing their privileges. A second faction was formed by many Galician nobles, who jockeyed for influence with Castilians for influence at the Leonese court. They feared the center of power would shift further eastward if Urraca's marriage was honored.

- Gerli, E. Michael (2013-12-04). Medieval Iberia: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-77162-0.

- Brooke, Z. N. (2019-06-26). A History of Europe 911-1198. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-50889-9.

- Weissberger, Barbara F. (2008). Queen Isabel I of Castile: Power, Patronage, Persona. Suffolk, UK: Tamesis Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-85566-159-2.

References

- Reilly, Bernard F. (1982). The Kingdom of Leon-Castilla under Queen Urraca. New York: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05344-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Urraca I of León and Castile. |

- Reilly, Bernard F. "The Kingdom of León-Castilla under Queen Urraca, 1109–1126"

- Reilly, Bernard F. The Medieval Spains, 1993.

Urraca of León House of Jiménez Born: April 1079 Died: 8 March 1126 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Alfonso VI |

Empress of Spain Queen of León Queen of Castile 1109–1126 |

Succeeded by Alfonso VII |

| Queen of Galicia 1109–1111 | ||

| Royal titles | ||

| Preceded by Bertha of Italy |

Queen consort of Aragon 1109–1114 |

Succeeded by Agnes of Aquitaine |

| Queen consort of Navarre 1109–1114 |

Succeeded by Marguerite de l'Aigle | |

.svg.png)