García II of Galicia

García II (1041/April 1043[1] – 22 March 1090), King of Galicia and Portugal,[lower-alpha 1] was the youngest of the three sons and heirs of Ferdinand I, King of Castile and León, and Sancha of León, whose Leonese inheritance included the lands García would be given. Garcia first appears in an 11 September 1064 settlement with Suero, Bishop of Mondoñedo, his father confirming the agreement.[2]

Accession

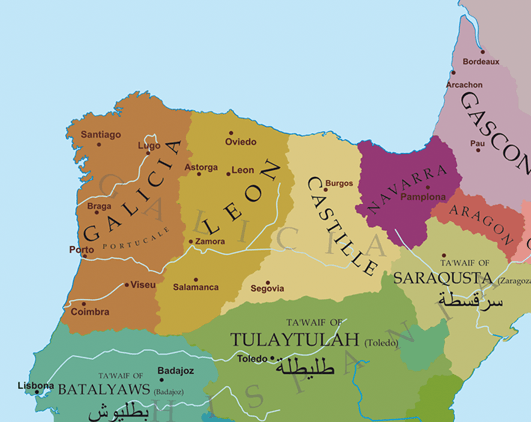

In the 1065 division of his father's estates, García was given the County of Galicia, "elevated to the rank of kingdom",[3] that extended south to the Mondego River in Portugal with the parias of the Taifa of Badajoz[3] and Seville;[4] his eldest brother Sancho received the Kingdom of Castile and the parias of the Taifa of Zaragoza.[5][6]. The second son and his father's favorite, Alfonso, fared best in this division, being given an expanded Kingdom of León[5] that encroached on lands that historically had been Castilian and Galician. Garcia's Galician kingdom was the most troubled, including lands south of the Duero over which firm administrative control had only been reestablished with the recapture of Coimbra the year before Ferdinand's death. Further, Ferdinand had begun a process intended to weaken the old comital house to bring the nobles more under direct royal control, but not yet finalized at his death. Further, the bishops of Lugo and Santiago were competing for preeminence.

Fraternal war

Among García's first acts was to receive the forced surrender of nearly the entire holdings of prominent nobleman García Múñoz. He also initiated plans to reestablish bishoprics at Braga, Lamego and Tui, as further tools for asserting royal authority, but suffered a significant setback when in 1068 the long-serving Bishop of Santiago died, then his successor was murdered the next year, an act that can be seen as a direct challenge to the king who might have been viewed as acting in an overly energetic manner, and indicating a loss of royal authority in Galicia. García seems to have turned his attention to strengthening his control in the south.[2] There he faced a challenge in early 1071 by the rebel Count of Portugal, Nuno Mendes,[7] whom García would defeat and kill at the Battle of Pedroso.[2]

García's brother and neighboring ruler, Alfonso, had been taking an interest in the increasingly unstable Galicia from at least 1070, and in May or early June 1071, he invaded Galicia and northern Portugal. Sancho likely acquiesced in this in exchange for partial control over the realm formerly belonging to his youngest brother. This scenario was untenable, as Alfonso's entire realm separated Sancho from Galicia, and the prospect of this further strengthening the already disproportionate power given Alfonso by their father was likely a driving force behind Sancho's attack on León that resulted in Alfonso's defeat and exile in 1072.[2] Sancho then turned his attention to García in central Portugal, defeating him near Santarém[2] and briefly imprisoning him in Castile (one chronicle specifying at Burgos) before he was then allowed to flee to Seville.[8] This reunited the realm their father had divided, and García's independent kingdom of Galicia and Portugal ceased to exist.[2]

Imprisonment

Events later in the same year precipitated García's return. In October, 1072, Sancho was assassinated at Zamora while suppressing a rebellion led by their sister Urraca, who had been given the rule of Zamora, and nobleman Pedro Ansúrez. Both dethroned brothers returned north, with Alfonso seizing Sancho's reunited realm. It is unclear if García hoped to reestablish himself in his kingdom or had been misled by promises of safety from Alfonso, but in February 1073, García was invited to a conference with Alfonso and there taken prisoner.[2] The earliest chronicles do not give the place of his imprisonment, but later chronicles put it at the castle of Luna, near León. There he remained until his death in or about 1090, the date given on his epitaph, due to a bloodletting after he developed a fever.[8]

King Garcia stated that he wished to be buried in chains, as he lived the final days of his life, and the king was represented as such on his tomb in the royal pantheon at the Basílica de San Isidoro, León. It included an inscription, since destroyed, that was reported to have borne a Latin epitaph:[8]

- H[ic] R[equiescit] DOMINUS GARCIA REX PORTUGALLIAE ET GALLECIAE. FILIUS REGIS MAGNI FERDINANDI. HIC INGENIO CAPTUS A FRATRE SUO IN VINCULIS. OBIIT ERA MCXXVIII XIº KAL[ends] APRIL[is].[9]

in English:

- Here lies Lord Garcia King of Portugal and Galicia, son of the great king Ferdinand. He was captured by his brother using a trick and placed in chains. He died on the 11th day before the kalends of April, Era 1128 (22 March 1090).

It is uncertain that this epitaph was carved immediately after García's death,[8] but it served as the basis for historian Ângelo Ribeiro to conclude that García was the first to use the title King of Portugal.[7] Because García died while the Council of León was in session, his funeral was attended by many eminent prelates, including papal legate Reniere, the future pope Pascal II.[8]

García's capture by trickery, long imprisonment and burial in great pomp made him a favorite of epic poets, and by the middle of the 12th century there was already a body of such poetic works. The earliest of these to survive is the 16th century ballad, Muerte de don García, rey de Galicia, desposeído por sus hermanos Sancho II y Alfonso VI de Castilla (The Death of García, king of Galicia, dispossessed by his brothers Sancho II and Alfonso VI of Castile), by Lorenzo de Sepúlveda. [8]

Notes

- Although he was the only García to hold this title, a unified numeral system has been used to enumerate the kings of Asturias, Galicia, León, and Castile, and the existence of an earlier García I of León made the King of Galicia "García II".

References

- Sánchez Candeira 1999, p. 227.

- Reilly, Bernard (1988). The Kingdom of León-Castilla under King Alfonso VI, 1065-1109. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Martínez Díez 2003, p. 33.

- Sánchez Candeira 1999, p. 231.

- Sánchez Candeira 1999, p. 230.

- Martínez Díez 2003, p. 31.

- Ribeiro, Sousa (2004). História de Portugal — A fundação do Reino , Volume 1 (in Portuguese). QuidNovi.

- Northup, George Tyler (1920). "The Imprisonment of King García". Modern Philology. 17: 393–411.

- Arco y Garay 1954, p. 188.

Bibliography

- Arco y Garay, Ricardo del (1954). Sepulcros de la Casa Real de Castilla (in Spanish). Madrid: Instituto Jerónimo Zurita. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. OCLC 11366237.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martínez Díez, Gonzalo (2003). Alfonso VI: Señor del Cid, conquistador de Toledo (in Spanish). Madrid: Temas de Hoy, S.A. ISBN 84-8460-251-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Portela Silva, Ermelindo (2001). Reyes privativos de Galicia: García I de Galicia, el rey y el reino (1065-1090) (in Spanish). Burgos: La Olmeda, S.L. ISBN 84-89915-16-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sánchez Candeira, Alfonso (1999). Rosa Montero Tejada (ed.). Castilla y León en el siglo X, estudio del reinado de Fernando I (in Spanish). Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia. ISBN 978-84-8951241-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Preceded by Ferdinand I |

King of Galicia 1065–1071 |

Succeeded by Alfonso VI Sancho II |