Uriah Heep

Uriah Heep is a fictional character created by Charles Dickens in his 1850 novel David Copperfield. Heep is one of the main antagonists of the novel. His character is notable for his cloying humility, obsequiousness, and insincerity, making frequent references to his own "'umbleness". His name has become synonymous with sycophancy.[1][2]

| Uriah Heep | |

|---|---|

| David Copperfield character | |

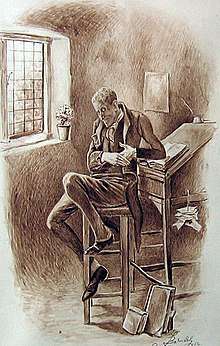

Drawing by Fred Barnard | |

| Created by | Charles Dickens |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Clerk |

| Family | Mrs. Heep (mother) |

| Nationality | British |

In the novel

David first meets the 15-year-old Heep when he comes to live with Mr Wickfield and his daughter Agnes.

Uriah is a law clerk working for Mr Wickfield. He realises that his widowed employer has developed a severe drinking problem, and turns it to his advantage. Uriah encourages Wickfield's drinking, tricks him into thinking he has committed financial wrongdoing while drunk, and blackmails him into making Uriah a partner in his law office. He admits to David (whom he hates) that he intends to manipulate Agnes into marrying him.

Uriah miscalculates when he hires Mr Micawber as a clerk, as he assumes that Micawber will never risk his own financial security by exposing Uriah's machinations and frauds. Yet Micawber is honest, and he, David, and Tommy Traddles confront Uriah with proof of his frauds. They only let Uriah go free after he has (reluctantly) agreed to resign his position and return the money that he has stolen.

Later in the novel, David encounters Uriah for the last time. Now in prison for bank fraud, and awaiting transportation, Uriah acts like a repentant model prisoner. However, in conversation with David he reveals himself to remain full of malice.

Origins

Much of David Copperfield is autobiographical, and some scholars believe Heep's mannerisms and physical attributes to be based on Hans Christian Andersen,[3][4] whom Dickens met shortly before writing the novel. Uriah Heep's schemes and behaviour are more likely based on Thomas Powell,[5] employee of Thomas Chapman, a friend of Dickens. Powell "ingratiated himself into the Dickens household" and was discovered to be a forger and a thief, having embezzled £10,000 from his employer. He later attacked Dickens in pamphlets, calling particular attention to Dickens' social class and background.

Characterisations of real people

The characteristics of grasping manipulation and insincerity can lead to a person being labelled "a Uriah Heep" as Lyndon Johnson is called in Robert Caro's biography The Years of Lyndon Johnson.[6] Author Philip Roth once compared President Richard Nixon to Uriah Heep.[7] More recently, historian Tony Judt used the term to describe Marshal Philippe Pétain of the French Vichy government.[8] Pakistani-British historian and leftist political commentator Tariq Ali likened Pakistani dictator Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq to the character. The late Australian journalist Padraic (Paddy) McGuinness, writing in The Australian Financial Review, referred to former Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating as Uriah Heep, after a fawning interview on ABC television in which Mr. Keating, the owner of extensive real estate holdings and a man generally acknowledged to have a robust ego, affected great humility. In the issue of asylum seekers, Lindsey Graham has been characterized as a Uriah Heep for his support of President Donald Trump's declaration of a national emergency in order to secure funding for a border wall.[9]

Film and television

In film and television adaptations, the character has been played by Peter Paget (1934),[10] Roland Young (1935), Colin Jeavons (1966), Ron Moody (1969), Martin Jarvis (1974), Paul Brightwell (1986), Nicholas Lyndhurst (1999), Frank MacCusker (2000) and Ben Whishaw (2018).[11]

Cultural references

The British rock band Uriah Heep is named after the character.[12] In the BBC television series Blake's 7, the computer character Slave was described by Peter Tuddenham, who voiced it, as "...a Uriah Heep type of character...."[13] A reference to the "'umble' Uriah Heep is the arrant hypocrite" is given in Augustus Hopkins Strong's Systematic Theology.[14] In Robert A. Caro's The Path to Power, Lyndon B. Johnson is said to have resembled the personality of Uriah Heep.[6] A reference to the character of Uriah Heep exists in the Half Life 2 franchise. A friendly character of one of the aliens from the game was considered, during development, to be a companion to the player for parts of the game, named "Heep". This idea was scrapped in the original game but recycled for Half-Life 2: Episode Two, where a lab assistant of the same species (who is treated with reverence) is named Uriah.[15] In the novel 'The Well of Lost Plots' by Jasper Fforde, the original form of Uriah Heep was portrayed as smart, intelligent, wise and very evil. A grab for power results in Heep's character being altered against his will into the more familiar form known in the books. [16]

Uriah Heep is mentioned in the title of H.G. Parry's book The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep, in which several literary characters, including Heep, escape from their respective books. [17]

References

- Oxford English Dictionary.

- Deborah Parker & Mark Parker (3 October 2017). "The 10 Biggest Sycophants from Literature and History". Electric Literature. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "Who's who in Dickens", by Donald Hawes. Thursday 1 October 2009.

- "Masterpiece Theatre: David Copperfield". Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- "The Extraordinary Life of Charles Dickens". Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- Caro, Robert A. (1982). The Path to Power. New York City: Random House. p. 489.

- Roth, Philip (October 1989). "Breast Baring". Vanity Fair. New York City: Condé Nast. p. 94.

- Judt, Tony (2010). Postwar. Vintage. p. 113.

- Sykes, Charles J. (18 March 2019). "The Senate GOP Hall of Fame and Hall of Shame". The Bulwark.

- "Peter Paget". British Pathé. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- "Uriah Heep". IMDb. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- Blows, Kirk. "Uriah Heep Story". www.uriah-heep.com. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- Attwood, Tony (1994). Blake's 7: The Programme Guide. London, England: Virgin Books. p. 225.

- Hopkins Strong, Augustus (1907). Systematic Theology. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American Baptist Publication Society. p. 832.

- Hodgson, David (2004). Half-life 2: Raising the Bar. Prima Games.

- Fforde, Jasper (2003). The Well of Lost Plots. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Parry, H.G. (2019). The Unlikely Escape of Uriah Heep. Hachette Book Group, Inc.