Shatt al-Arab

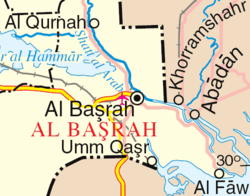

The Shatt al-Arab (Arabic: شط العرب, River of the Arabs),[2] also known as Arvand Rud (Persian: اروندرود, Swift River), is a river of some 200 km (120 mi) in length formed by the confluence of the Euphrates and the Tigris in the town of al-Qurnah in the Basra Governorate of southern Iraq. The southern end of the river constitutes the border between Iraq and Iran down to the mouth of the river as it discharges into the Persian Gulf. It varies in width from about 232 metres (761 ft) at Basra to 800 metres (2,600 ft) at its mouth. It is thought that the waterway formed relatively recently in geologic time, with the Tigris and Euphrates originally emptying into the Persian Gulf via a channel further to the west.

| Shatt al-Arab Arvand Rud | |

|---|---|

| Native name | Arabic: شط العرب Persian: اروندرود |

| Location | |

| Country | Iran, Iraq |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Tigris–Euphrates confluence at Al-Qurnah and Karun River in Iran[1] |

| • elevation | 4 m (13 ft) |

| Mouth | |

• location | Persian Gulf |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 200 km (120 mi) |

| Basin size | 884,000 km2 (341,000 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 1,750 m3/s (62,000 cu ft/s) |

The Karun River, a tributary which joins the waterway from the Iranian side, deposits large amounts of silt into the river; this necessitates continuous dredging to keep it navigable.[3]

The area is judged to hold the largest date palm forest in the world. In the mid-1970s, the region included 17 to 18 million date palms, an estimated one-fifth of the world's 90 million palm trees. But by 2002, war, salt, and pests had wiped out more than 14 million of the palms, including around 9 million in Iraq and 5 million in Iran. Many of the remaining 3 to 4 million trees are in poor condition.[4]

In Middle Persian literature and the Shahnameh (written between c. 977 and 1010 AD), the name اروند Arvand is used for the Tigris, the confluent of the Shatt al-Arab.[5] Iranians also used this name specifically to designate the Shatt al-Arab during the later Pahlavi period, and continue to do so after the Iranian Revolution of 1979.[5]

Geography

Shatt al-Arab river is made by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates river at Al-Qurnah and continues to end up at the Persian gulf south of the city of Al-Faw. According to a study, the river appears to have formed in the recent Earth's geologic time scale in comparison between lithoaces and biofacies of previous studies. The river may have formed 2000–1600 years prior to the 21st century.[6]

History

The background of the issue stretches mainly back to the Ottoman-Safavid era, prior to the establishment of an independent Iraq, which happened in the 20th century. In the early 16th century, the Iranian Safavids gained most of what is present-day Iraq, but lost it later by the Peace of Amasya (1555) to the expanding Ottomans.[7] In the early 17th century, the Safavids under king (shah) Abbas I (r. 1588–1629) regained it, only to lose it permanently (along, temporarily, with control over the waterway), to the Ottomans by the Treaty of Zuhab (1639).[8] This treaty, which roughly re-established the common borders of the Ottoman and Safavid Empires the way they had been in 1555, never demarcated a precise and fixed boundary regarding the frontier in the south. Nader Shah (r. 1736–1747) restored Iranian control over the waterway, but the Treaty of Kerden (1746) restored the Zuhab boundaries, and ceded it back to the Turks.[9][10] The First Treaty of Erzurum (1823) concluded between Ottoman Turkey and Qajar Iran, resulted in the same.[11][12]

The Second Treaty of Erzurum was signed by Ottoman Turkey and Qajar Iran in 1847 after protracted negotiations, which included British and Russian delegates. Even afterwards, backtracking and disagreements continued, until British Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, was moved to comment in 1851 that "the boundary line between Turkey and Persia can never be finally settled except by an arbitrary decision on the part of Great Britain and Russia". A protocol between the Ottomans and the Persians was signed in Istanbul in 1913, which declared that the Ottoman-Persian frontier run along the thalweg, but World War I canceled all plans.

During the Mandate of Iraq (1920–32), the British advisors in Iraq were able to keep the waterway binational under the thalweg principle that worked in Europe: the dividing line was a line drawn between the deepest points along the stream bed. In 1937, Iran and Iraq signed a treaty that settled the dispute over control of the Shatt al-Arab.[13] The 1937 treaty recognized the Iranian-Iraqi border as along the low-water mark on the eastern side of the Shatt al-Arab except at Abadan and Khorramshahr where the frontier ran along the thalweg (the deep water line) which gave Iraq control of almost the entire waterway; provided that all ships using the Shatt al-Arab fly the Iraqi flag and have an Iraqi pilot, and required Iran to pay tolls to Iraq whenever its ships used the Shatt al-Arab.[14] The treaty of 1937 marked a familiar pattern by British empire of Divide and rule that was routinely employed in the Indian subcontinent and other British colonial or influenced regions: it ensured long term if not permanent tension between Iran and Iraq. As opposed to using the thalweg principle as advised during 1920–1932 period, which would have calmed down or ended the river border tensions between the two nations.

The Shatt al-Arab and the forest were depicted in the middle of the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Iraq, from 1932–1959.

Under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in the late 60s, Iran developed a strong military and took a more assertive stance in the Near East.[13] In April 1969, Iran abrogated the 1937 treaty over the Shatt al-Arab and Iranian ships stopped paying tolls to Iraq when they used the Shatt al-Arab.[15] The Shah argued that the 1937 treaty was unfair to Iran because almost all river borders around the world ran along the thalweg, and because most of the ships that used the Shatt al-Arab were Iranian.[16] Iraq threatened war over the Iranian move, but on 24 April 1969, an Iranian tanker escorted by Iranian warships (Joint Operation Arvand) sailed down the Shatt al-Arab, and Iraq—being the militarily weaker state—did nothing.[14] The Iranian abrogation of the 1937 treaty marked the beginning of a period of acute Iraqi-Iranian tension that was to last until the Algiers Accords of 1975.[14]

All United Nations attempts to intervene and mediate the dispute were rebuffed. Under Saddam Hussein, Baathist Iraq claimed the entire waterway up to the Iranian shore as its territory. In response, Iran in the early 1970s became the main patron of Iraqi Kurdish groups fighting for independence from Iraq. In March 1975, Iraq signed the Algiers Accord in which it recognized a series of straight lines closely approximating the thalweg (deepest channel) of the waterway, as the official border, in exchange for which Iran ended its support of the Iraqi Kurds.[17]

In 1980, Hussein released a statement claiming to abrogate the 1975 treaty and Iraq invaded Iran. International law, however, holds that in all cases no bilateral or multilateral treaty can be abrogated by one party only. The main thrust of the military movement on the ground was across the waterway which was the stage for most of the military battles between the two armies. The waterway was Iraq's only outlet to the Persian Gulf, and thus, its shipping lanes were greatly affected by continuous Iranian attacks.[17]

When the Al-Faw peninsula was captured by the Iranians in 1986, Iraq's shipping activities virtually came to a halt and had to be diverted to other Arab ports, such as Kuwait and even Aqaba, Jordan. At the end of the Iran–Iraq War, both sides agreed to once again treat the Algiers Accord as binding.

Conflicts

Iranian-Iraqi dispute

Conflicting territorial claims and disputes over navigation rights between Iran and Iraq were among the main factors for the Iran–Iraq War that lasted from 1980 to 1988, when the pre-1980 status quo was restored. The Iranian cities and major ports of Abadan and Khorramshahr and the Iraqi cities and major ports of Basra and Faw are situated along this river.

2003 invasion of Iraq

In the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the waterway was a key military target for the Coalition Forces. Since it is the only outlet to the Persian Gulf, its capture was important in delivering humanitarian aid to the rest of the country, and also to stop the flow of operations trying to break the naval blockade against Iraq. The British Royal Marines staged an amphibious assault to capture the key oil installations and shipping docks located at Umm Qasr on the al-Faw peninsula at the onset of the conflict.

Following the end of the war, the UK was given responsibility, subsequently mandated by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1723, to patrol the waterway and the area of the Persian Gulf surrounding the river mouth. They were tasked until 2007 to make sure that ships in the area were not being used to transport munitions into Iraq. British forces also trained Iraqi naval units to take over the responsibility of guarding their waterways after the Coalition Forces left Iraq in December 2011.

On two separate occasions, Iranian forces operating on the Shatt al-Arab captured British Royal Navy sailors who they claim trespassed into their territory.

- In 2004, several British servicemen were held for two days after purportedly straying into the Iranian side of the waterway. After being initially threatened with prosecution, they were released after high-level conversations between British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw and Iranian Foreign Minister Kamal Kharrazi. The initial hardline approach was put down to power struggles within the Iranian government. The British marines' weapons and boats were confiscated.

- In 2007, a seizure of fifteen more British personnel became a major diplomatic crisis between the two nations. It was resolved after thirteen days when the Iranians unexpectedly released the captives under an "amnesty."

See also

References

- "Iraq – Major Geographical Features". country-data.com. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- https://krfps.ru/en/osnaschenie/kak-dobratsya-iz-milana-v-rim-siesta-v-italii-milan-rabotaet-rim.html

- "Iraq – Major Geographical Features". country-data.com. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- "UNEP/GRID-Sioux Falls". unep.net. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- M. Kasheff, Encyclopædia Iranica: Arvand-Rud. – Retrieved on 18 October 2007.

- Al-Hamad; et al. "Geological History of Shatt Al-Arab River, South of Iraq". International Journal of Science and Research. ISSN 2319-7064.

- Mikaberidze 2015, p. xxxi.

- Dougherty & Ghareeb 2013, p. 681.

- Shaw 1991, p. 309.

- Marschall, Christin (2003). Iran's Persian Gulf Policy: From Khomeini to Khatami. Routledge. pp. 1–272. ISBN 978-1134429905.

- Kia 2017, p. 21.

- Potts 2004.

- Karsh, Efraim The Iran-Iraq War 1980–1988, London: Osprey, 2002 page 7

- Karsh, Efraim The Iran-Iraq War 1980–1988, London: Osprey, 2002 page 8

- Karsh, Efraim The Iran-Iraq War 1980–1988, London: Osprey, 2002 pages 7–8

- Bulloch, John and Morris, Harvey The Gulf War, London: Methuen, 1989 page 37.

- Abadan Archived 2009-08-08 at the Wayback Machine, Sajed, Retrieved on March 16, 2009.

Sources

- Dougherty, Beth K.; Ghareeb, Edmund A. (2013). Historical Dictionary of Iraq (2 ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810879423.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kia, Mehrdad (2017). The Ottoman Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693899.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Potts, D. T. (2004). "SHATT AL-ARAB". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaw, Stanford (1991). "Iranian Relations with the Ottoman Empire in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries". In Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol. 7). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0857451842.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shatt al-Arab. |