Untertorbrücke

The Untertorbrücke (German: Lower Gate Bridge) is a stone arch bridge that spans the Aare at the easternmost point of the Enge peninsula in the city of Bern, Switzerland, connecting the Mattequartier in the Old City to the Schosshalde neighbourhood. Built in its current form in 1461–89, it is the oldest of Bern's Aare bridges, and was the city's only bridge up until the middle of the 19th century. It is a Swiss heritage site of national significance.[2]

Untertorbrücke | |

|---|---|

The Untertorbrücke as seen from the Nydeggbrücke | |

| Coordinates | 46°56′57.96″N 7°27′30.47″E |

| Carries | Two lanes and sidewalks |

| Crosses | Aare |

| Locale | Bern, Switzerland |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Arched lintel bridge |

| Material | Natural stone (Sandstone, tuff) |

| Total length | 52.5 meters (172 ft) |

| Width | 7.5 meters (25 ft) |

| Height | 8.1 meters (27 ft) |

| Longest span | 15.1 meters (50 ft) |

| No. of spans | 3[1] |

| Piers in water | 2 |

| Clearance below | 4.3 meters (14 ft) |

| History | |

| Construction start | 1461 |

| Construction end | 1489 |

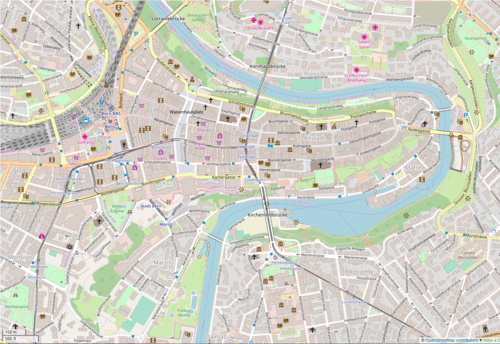

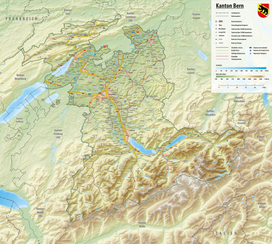

Untertorbrücke Location in Bern  Untertorbrücke Untertorbrücke (Canton of Bern)  Untertorbrücke Untertorbrücke (Switzerland) | |

History

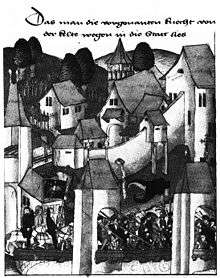

Wooden bridge, 1255

The need for a river crossing became urgent soon after the founding of Bern in 1191.[3] The young city-state's first attempt at building a wooden bridge over the Aare triggered a war with Count Hartmann of the powerful House of Kyburg that controlled the territory east of the Aare.[4] Thanks to a peace mediated by Savoy, the first Untertorbrücke could be completed in 1256.[5] In 1288, it survived a heavy attack during King Rudolph of Habsburg's second siege of Bern.[6]

The bridge was built from oak wood and is believed to have been at least partially covered.[3] It was protected by a fortified tower to the east, carried a guard house in its center and may also have been built over with other houses or shacks.[7]

Construction of the stone bridge, 1461

A 1460 flood of the Aare caused severe damage to the bridge, and the city government decided to rebuild it in stone,[7] requesting the services of a work master from Zürich who had then recently completed a bridge over the Limmat in Baden.[8] The piers appear to have been complete and the bridge largely usable by March 1467, when the bridge chapel was consecrated.[8] The construction was then halted because of massive cost overruns and intermittent wars. It resumed in 1484–87 with the completion of the fortifications, the bridgehead drawbridge and the access roads.[9]

Up until the 1750s, the bridge's fortifications were repeatedly improved. The parapet was strengthened with crenellated stone walls in 1517, and the northern parapet was expanded to a covered battlement with a double layer of embrasures in 1625–30.[10]

Reshaping the bridge, 1757 and 1818

In the 18th century, the medieval fortifications of the Untertorbrücke had lost their military value and increasingly became an obstacle to traffic. In 1757, the bridge was thoroughly renovated and a competition was held for a remodeling of the bridge and its surroundings.[11] The city councils, however, rejected all the fanciful plans that were submitted and settled on a cheaper option: all fortifications, including battlements and pillar gates, were removed and new decorative gates were built at the bridgeheads, including a baroque triumphal arch at the eastern end.[11]

From 1818 on, more changes were made to the bridge's superstructure. The sandstone parapets were replaced with iron railings, the inner gate (now isolated) was removed and the eastern moat was filled with earth, obviating the outer drawbridge.[12] The last substantial change to the bridge's appearance was made in 1864, when the eastern gate was pulled down because it inconvenienced the residents of the medieval guard tower, the Felsenburg, which had since been converted for residential purposes.[13]

Current state

In its current form, the bridge is reduced to the medieval construction core, with no traces of the once extensive system of fortifications or imposing baroque gates remaining.[14] The two great piers, whose unequal strength recalls the stronger build of the former eastern pier gate, are built of sandstone and are faced by granite slabs from the 1820s.[14] At the eastern bridgehead, the two-lane road bends to the south where it once passed beneath the former guard tower. The stones of the three slender tuff arches date back to the construction period, while the Neo-gothic wrought-iron railing was installed in 1819.[15]

The state of the superstructure largely reflects that of the early 19th century.[15] The cobbled roadbed, which carries two lanes amenable to motor traffic as well as sidewalks, was replaced in the bridge's last thorough renovation in 1979–81.[16]

References

- Furrer, Bernhard (1984), Übergänge: Berner Aareebrücken, Geschichte und Gegenwart, Bern: Benteli, ISBN 3-7165-0492-0

- Hofer, Paul (1959), Die Stadt Bern., Kunstdenkmäler des Kantons Bern, 1, Basel: Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte / Verlag Birkhäuser, pp. 193–224, ISBN 3-906131-13-0

- Caviezel, Zita; Herzog, Georges; Keller, Jürg A. (2006), Basel-Landschaft, Basel-Stadt, Bern, Solothurn, Kunstführer durch die Schweiz, 3 (1st ed.), Bern: Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte, p. 248, ISBN 3-906131-97-1

Footnotes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Untertorbrücke. |

- All construction data are from Furrer, 155.

- "Kantonsliste A-Objekte". KGS Inventar (in German). Federal Office of Civil Protection. 2009. Archived from the original on 28 June 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- Furrer, 7.

- Furrer, 7; Hofer, 195.

- Furrer, 7; Hofer, 196.

- Hofer, 196.

- Furrer, 7; Hofer, 197.

- Furrer, 7; Hofer, 198.

- Furrer, 7; Hofer, 199.

- Furrer, 8; Hofer, 200–203.

- Furrer, 10.

- Furrer, 10; Hofer, 208.

- Furrer, 10; Hofer, 209.

- Furrer, 11; Hofer, 209.

- Furrer, 11; Hofer, 210.

- Caviezel, 163.