USS Michigan (BB-27)

USS Michigan (BB-27), a South Carolina-class battleship, was the second ship of the United States Navy to be named in honor of the 26th state. She was the second member of her class, the first dreadnought battleships built for the US Navy. She was laid down in December 1906, launched in May 1908; sponsored by Mrs. F. W. Brooks, daughter of Secretary of the Navy Truman Newberry; and commissioned into the fleet 4 January 1910. Michigan and South Carolina were armed with a main battery of eight 12-inch (305 mm) guns in superfiring twin gun turrets; they were the first dreadnoughts to feature this arrangement.

USS Michigan (BB-27) in 1912 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Michigan |

| Namesake: | State of Michigan |

| Builder: | New York Shipbuilding Corporation |

| Laid down: | 17 December 1906 |

| Launched: | 26 May 1908 |

| Commissioned: | 4 January 1910 |

| Decommissioned: | 11 February 1922 |

| Stricken: | 10 November 1923 |

| Fate: | Sold for scrap |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | South Carolina-class battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 80 ft 3 in (24 m) |

| Draft: | 24 ft 6 in (7 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 18.5 kn (21 mph; 34 km/h) |

| Range: | 6,950 nmi (7,998 mi; 12,871 km) at 10 kn (12 mph; 19 km/h) |

| Complement: | 869 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

Michigan spent her career in the Atlantic Fleet. She frequently cruised the east coast of the United States and the Caribbean Sea, and in April 1914 took part in the United States occupation of Veracruz during the Mexican Civil War. After the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Michigan was employed as a convoy escort and training ship for the rapidly expanding wartime navy. In January 1918, her forward cage mast collapsed in heavy seas, killing six men. In 1919, she ferried soldiers back from Europe. The ship conducted training cruises in 1920 and 1921, but her career was cut short by the Washington Naval Treaty signed in February 1922, which mandated the disposal of Michigan and South Carolina. Michigan was decommissioned in February 1923 and broken up for scrap the following year.

Design

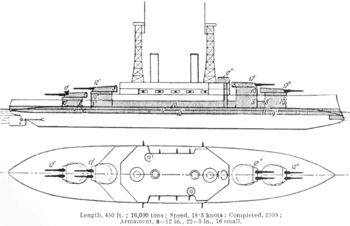

Michigan was 452 ft 9 in (138 m) long overall and had a beam of 80 ft 3 in (24 m) and a draft of 24 ft 6 in (7 m). She displaced 16,000 long tons (16,257 t) as designed and up to 17,617 long tons (17,900 t) at full load. The ship was powered by two-shaft vertical triple-expansion engines rated at 16,500 ihp (12,304 kW) and twelve coal-fired Babcock & Wilcox boilers, generating a top speed of 18.5 kn (34 km/h; 21 mph). The ship had a cruising range of 5,000 nmi (9,260 km; 5,754 mi) at a speed of 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph). She had a crew of 869 officers and men.[1]

The ship was armed with a main battery of eight 12-inch (305 mm)/45[lower-alpha 1] caliber Mark 5 guns in four twin gun turrets on the centerline, which were placed in two superfiring pairs forward and aft. The secondary battery consisted of twenty-two 3-inch (76 mm)/50 guns mounted in casemates along the side of the hull. As was standard for capital ships of the period, she carried a pair of 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes, submerged in her hull on the broadside.[1]

Michigan's main armored belt was 12 in (305 mm) thick over the magazines, 10 in (254 mm) over the machinery spaces, and 8 in (203 mm) elsewhere. The armored deck was 1.5 to 2.5 in (38 to 64 mm) thick. The gun turrets had 12 inch thick faces, while the supporting barbettes had 10 inch thick armor plating. Ten inch thick armor also protected the casemate guns. The conning tower had 12 inch thick sides.[1]

Service history

Michigan was laid down on 17 December 1906 at the New York Shipbuilding Corporation. Her completed hull was launched on 26 May 1908. Fitting out work was completed by 4 January 1910, when she was commissioned into the US Navy.[1][2] After entering service, she was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet. She then began a shakedown cruise down to the Caribbean Sea that lasted until 7 June. Michigan joined training maneuvers off New England beginning on 29 July. A training cruise to Europe followed; she departed Boston, Massachusetts, on 2 November and stops included Portland in the United Kingdom and Cherbourg, France. She arrived in the latter port on 8 December and remained there until the 30th, when she left for the Caribbean. The ship reached Guantanamo Bay, Cuba on 10 January 1911 and continued on to Norfolk, arriving four days later.[2] During this period, future naval aviation pioneer John Henry Towers served aboard the ship as a spotter for the main guns. The long range of the guns, which could shoot further than the horizon, convinced Towers of the need for spotter aircraft.[3]

The ship then cruised the east coast for most of the next two years. On 15 November 1912, she departed for a longer cruise to the Gulf of Mexico, with stops in Pensacola, Florida, New Orleans, Louisiana, and Galveston, Texas, on the way. She then continued further south to Veracruz, Mexico, where she arrived on 12 December. Michigan remained there for two days before beginning the voyage home; she reached Hampton Roads on 20 December. Patrols off the east coast resumed for the first half of 1913. On 6 July, she steamed out of Quincy, Massachusetts, for another voyage to Mexican waters; this trip was prompted by the Mexican Civil War, which threatened American interests in the country. She arrived off Tampico on 15 July and thereafter cruised the Mexican coast until 13 January 1914, when she departed for New York City, arriving seven days later. She then transferred back to Norfolk.[2]

On 14 February, she left the port for a short voyage to Guacanayabo Bay, Cuba, and was back in Hampton Roads by 19 March. Michigan began a third cruise to Mexico on 16 April to support the United States occupation of Veracruz. She reached the city on 22 April and landed a battalion of Marines as part of the occupation force. The ship then patrolled the coast before departing for the United States on 20 June. She reached the Delaware Capes six days later. The normal peacetime routine of cruises off the east coast continued for the next three years.[2] In December 1914, the ship's crew experimented with fire control directors to aid in gunlaying; the experimental directors produced significantly improved results in gunnery tests conducted in early 1915.[4] In September 1916, Michigan conducted gunnery practice with the old monitor Miantonomoh as a target, including night shooting drills on the 18th. On 21 September, during another round of shooting at Miantomomoh, the shell in the left gun in Michigan's forward superfiring turret exploded. The gun was severed where it exited the turret and fragments from the shell damaged the forecastle deck and the superstructure. One man was injured by a piece of debris. Michigan returned to the Philadelphia Navy Yard for repairs, arriving there two days later.[5][6]

World War I

On 6 April 1917, the United States declared war on Germany over its unrestricted submarine warfare campaign. Due to her slow speed, Michigan was assigned to Battleship Force 2 that day, and was tasked with training naval recruits and escorting convoys. As part of the training mission, she participated in fleet maneuvers and gunnery exercises. On 15 January 1918, Michigan was cruising off Cape Hatteras on a training exercise when a heavy gale and rough seas knocked over the forward cage mast.[2] The ship had rolled to port in the heavy seas before rolling sharply back to starboard. The rapid change in direction caused the mast to snap at its narrowest point, which had been damaged in the 1916 barrel explosion and patched over.[7] The accident killed six men and injured another thirteen. Michigan steamed to Norfolk, transferred the injured men to the hospital ship Solace, and went to the Philadelphia Navy Yard for repairs, arriving on 22 January.[2]

By early April, Michigan was back in service; for the next several months, she primarily trained gunners in the Chesapeake Bay. While on a convoy escort that had left the United States on 30 September, the ship's port screw fell off. She was forced to leave the convoy on 8 October and return to port for repairs, remaining out of service for the rest of the war.[8] In November 1918, Germany signed the Armistice that ended the fighting in Europe. Michigan was assigned to the Cruiser and Transport Force in late December 1918 to ferry American soldiers back from Europe. She made two round trips in 1919 during the operation, the first from 18 January to 3 March, and the second from 18 March to 16 April, bringing back 1,062 men in the two voyages.[2]

Post-war period

_1918.jpg)

In May, Michigan was sent to Philadelphia for an overhaul that lasted through June. She thereafter returned to her peacetime training routine. On 6 August, she was reduced to limited commission and stationed at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. On 19 May 1920, she steamed to Annapolis to pick up a contingent of midshipmen for a major training cruise. After departing Annapolis, the ship steamed south and transited the Panama Canal before proceeding to Honolulu, Hawaii, where she arrived on 3 July. Michigan visited several naval bases on the west coast of the United States through the summer: Seattle, San Francisco, San Pedro, and San Diego, before returning to Annapolis on 2 September. Three days later, she was back in Philadelphia, where she was temporarily decommissioned.[2]

Michigan was reactivated in 1921 for another cruise to the Caribbean, departing on 4 April. She returned to Philadelphia on 23 April;[2] shortly thereafter, the ship became embroiled in a minor scandal. The ship's commanding officer at the time, Clark Daniel Stearns, instituted a series of sailors' committees on 3 May to ease tensions between officers and the crew. The commanders of the Atlantic Fleet and Michigan's squadron decided that the committees were a threat to discipline and evidence of Marxist influences. They contacted Edwin Denby, then the Secretary of the Navy, who relieved Stearns of command.[9] On 28 May, she picked up another group of midshipmen for another training cruise. This voyage took the ship to Europe, with stops in a number of ports, including Christiana, Norway, Lisbon, Portugal, and Gibraltar. She returned to Hampton Roads via Guantanamo Bay on 22 August.[2]

In the years immediately following the end of the Great War, the United States, Britain, and Japan all launched huge naval construction programs. All three countries decided that a new naval arms race would be ill-advised, and so convened the Washington Naval Conference to discuss arms limitations, which produced the Washington Naval Treaty, signed in February 1922.[10] Under the terms of Article II of the treaty, Michigan and her sister South Carolina were to be scrapped.[11] Michigan put to sea for the last time on 31 August, bound for the breaker's yard in Philadelphia. She arrived there on 1 September and was decommissioned on 11 February 1923. She was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 10 November and broken up for scrap the following year.[2]

Footnotes

Notes

- /45 refers to the length of the gun in terms of calibers. A /45 gun is 45 times long as it is in bore diameter.

Citations

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 112.

- DANFS Michigan.

- Murray & Millett, p. 387.

- Friedman, p. 179.

- Schwerin, p. 26.

- Jones, p. 114.

- Jones, pp. 113–114.

- Noppen, p. 30.

- Guttridge, p. 179.

- Potter, pp. 232–233.

- Washington Naval Treaty, Chapter I: Article II.

References

- Friedman, Norman (2008). Naval Firepower: Battleship Guns and Gunnery in the Dreadnought Era. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-555-4.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Guttridge, Leonard F. (1992). Mutiny: A History of Naval Insurrection. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870212818.

- Jones, Jerry W. (1998). U.S. Battleship Operations in World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-411-3.

- "Michigan (BB-27) ii". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History & Heritage Command. 4 February 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- Murray, Williamson R. & Millett, Alan R., eds. (1998). Military Innovation in the Interwar Period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521637600.

- Noppen, Ryan (2014). US Navy Dreadnoughts 1914–45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781782003885.

- Potter, E, ed. (1981). Sea Power: A Naval History (2nd ed.). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-607-4.

- Schwerin, J. P. (1916). Ketcham, Charles A. (ed.). "U.S.S. Michigan". The Marines Magazine. Vol. 2 no. 1. pp. 26–27. OCLC 656877870.

External links

![]()