Universal Postal Union

The Universal Postal Union (UPU, French: Union postale universelle), established by the Treaty of Bern of 1874,[1] is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) that coordinates postal policies among member nations, in addition to the worldwide postal system. The UPU contains four bodies consisting of the Congress, the Council of Administration (CA), the Postal Operations Council (POC) and the International Bureau (IB). It also oversees the Telematics and Express Mail Service (EMS) cooperatives. Each member agrees to the same terms for conducting international postal duties. The UPU's headquarters are located in Bern, Switzerland.[2]

| |

| |

| Abbreviation | UPU |

|---|---|

| Formation | 9 October 1874 |

| Type | United Nations specialised agency |

| Legal status | Active |

| Headquarters | Bern, Switzerland |

Head | Director-General Bishar Abdirahman Hussein |

Parent organization | United Nations Economic and Social Council |

| Website | www.upu.int |

| Treaty effective October 1874 | |

History

Before the Postal Union

Before the establishment of the UPU, every pair of countries that exchanged mail had to negotiate a postal treaty with each other. In the absence of a treaty providing for direct delivery of letters, senders sometimes resorted to mail forwarders who would transfer the mail through an intermediate country.[4]

Negotiations for postal treaties could drag on for years. When Elihu Washburne arrived in Paris in 1869 as the new United States Minister to France, he found "the singular spectacle ... of no postal arrangements between two countries connected by so many business and social relations."[5]:13–14 At the last grand dinner given by Emperor Napoleon III before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, the first topic he discussed with Washburne was the postal treaty.[5]:38 After Napoleon III was defeated at the Battle of Sedan, the United States became the first country to recognize the French Third Republic, an event that brought thousands of Parisians into the street shouting "Vive l'Amérique."[5]:124 However, such sentiments did not lead to the signing of a postal treaty between the United States and France. There would be no relief until the Postal Union was established in 1874.[5]:14[6]:254–255 Washburne wrote, "There is no nation in the world more difficult to make treaties with than France."[5]:13

Faced with such difficulties, the United States took the lead in calling for improvements to international mail arrangements. United States Postmaster General Montgomery Blair called for an International Postal Congress in 1863. Meeting in Paris, the delegates laid down some general principles for postal cooperation but failed to come to an agreement.[7]

General Postal Union

The task was taken up by Heinrich von Stephan, the Postmaster-General of the German Reichspost. After defeating Napoleon III in 1870, the North German Confederation and the South German states united to form the German Empire. The Reichspost established a uniform set of postage rates and regulations for the new country. However, the uniformity ended at the German border. Mailing a letter from Berlin to New York required different amounts of postage, depending on which ship carried the letter across the Atlantic Ocean.[8] To bring order to the system of international mail, von Stephan called for another International Postal Congress in 1874.[8]

Meeting in Bern, Switzerland, the delegates agreed to all of von Stephan's proposals.[8] The Treaty of Bern was signed on October 9, 1874, establishing what was then known as the General Postal Union.[9]

The treaty provided that:

- There should be a uniform flat rate to mail a letter anywhere in the world

- Postal authorities should give equal treatment to foreign and domestic mail

- Each country should retain all money it has collected for international postage.

One important result of the Treaty was that it was no longer necessary to affix postage stamps of countries that a mailpiece passed through in transit. The UPU provides that stamps from member nations are accepted along the entire international route.

Universal Postal Union

The Treaty of Bern had been signed by 21 countries, 19 of which were located in Europe.[nb 1] After the General Postal Union was established, its membership grew rapidly as other countries joined. At the second Postal Union Congress in 1878, it was renamed the Universal Postal Union.[7]

French was the sole official language of the UPU. English was added as a working language in 1994. The majority of the UPU's documents and publications – including its flagship magazine, Union Postale – are available in the United Nations' six official languages French, English, Arabic, Chinese, Russian, and Spanish.[10]

Toward the end of the 19th century, the UPU issued rules concerning stamp design, intended to ensure maximum efficiency in handling international mail. One rule specified that stamp values be given in numerals, as denominations written out in letters were not universally comprehensible.[11] Another required member nations to use the same colors on their stamps issued for post cards (green), normal letters (red) and international mail (blue), a system that remained in use for several decades.[12]

After the foundation of the United Nations, the UPU became a specialized agency of the UN in 1948.[13] It is currently the third oldest international organization after the Rhine Commission and the International Telecommunication Union.

Terminal dues

Origin

The 1874 treaty provided for the originating country to keep all of the postage revenue, without compensating the destination country for delivery. The idea was that each letter would generate a reply, so the postal flows would be in balance.[14][15] However, other classes of mail had imbalanced flows. In 1906, the Italian postal service was delivering 325,000 periodicals mailed from other countries to Italy, while Italian publishers were mailing no periodicals to other countries.[15] The system also encouraged countries to remail through another country, forcing the intermediate postal service to bear the costs of transport to the final destination.[16]

Remailing was banned in 1924, but the UPU took no action on imbalanced flows until 1969. The problem of imbalanced flows became acute after decolonization, as dozens of former European colonies entered the UPU as independent states. The developing countries received more mail than they sent, so they wanted to be paid for delivery.[15]

In 1969, the UPU introduced a system of terminal dues. When two countries had imbalanced mail flows, the country that sent more mail would have to pay a fee to the country that received more mail. The amount was based on the difference in the weight of mail sent and received.[15] Since the Executive Council had been unable to come up with a cost-based compensation scheme after five years of study, terminal dues were set arbitrarily at half a gold franc (0.163 SDR) per kilogram.[16]

Modifications

Once terminal dues had been established, they became a topic of discussion at every future Postal Union Congress. The 1974 Congress tripled the terminal dues to 1.5 gold francs, and the 1979 Congress tripled them again to 4.5 gold francs. The 1984 Congress increased terminal dues by another 45%.[16]

The system of terminal dues also created new winners and losers. Since the terminal dues were fixed, low-cost countries that were net recipients would turn a profit on delivering international mail. Developing countries were low-cost recipients, but so were developed countries like the United States and the United Kingdom.[15] Since the dues were payable based on weight, periodicals would be assessed much higher terminal dues than letters.[14]

The continuing fiscal imbalances required repeated changes to the system of terminal dues. In 1988 a per-item charge was included in terminal dues to drive up the cost of remailing, an old scourge that had returned.[16] To resolve the problem with periodicals, the UPU adopted a "threshold" system in 1991 that set separate letter and periodical rates for countries which receive at least 150 tonnes of mail annually.[14] The 1999 Postal Congress established "country-specific" terminal dues for industrialized countries, offering a lower rate to developing countries.[16]

Shifting balances and the United States

In 2010, the United States was a net sender because it was mailing goods to other countries. That year, the United States Postal Service made a $275 million surplus on international mail.[17] In addition, the UPU system was only available to state-run postal services. Low terminal dues gave the United States Postal Service an advantage over private postal services such as DHL and FedEx. To protect its profits on sending international mail, the United States voted with the developing countries to keep terminal dues low. They were opposed by the German Bundespost and the Norwegian Post, which wanted to increase terminal dues.[15]

However, the low terminal dues backfired on the United States due to shifts in mail flows. With the growth of e-commerce, the United States began to import more goods through the mail. In 2015, the United States Postal Service made a net deficit on international mail for the first time. The deficits increased to $80 million in 2017.[17] The UPU established a new remuneration system in 2016,[18] a move that the United States Department of State said would "dramatically improv[e] USPS's cost coverage for the delivery of ... packets from China and other developing countries." However, the Chairman of the Postal Regulatory Commission disagreed.[19]

2019 Extraordinary Congress

With the outbreak of the China–United States trade war in 2018, the issue of terminal dues was pushed into the forefront. Americans complained that mailing a package from China to the United States cost less than mailing the same package within the United States. At the time, the UPU's Postal Development Indicator scale was used to classify countries into four groups from richest to poorest. The United States was a Group I country, while China was a Group III country, alongside countries like Mexico and Turkey that had similar GDP per capita. As a result, China paid lower terminal dues than the United States.[19]:38 The Donald Trump administration complained that it was "being forced to heavily subsidize small parcels coming into our country."[20] On 17 October 2018, the United States declared its withdrawal from the UPU, effective one year later, when it would self-declare the rates charged to other postal services.[21]

The Universal Postal Union responded in May 2019 by calling, for only the third time in its history, an Extraordinary Congress for 24–26 September 2019.[22] The members voted down a proposal submitted by the United States and Canada,[23] which would have allowed immediate self-declaration of terminal dues.[24] The UPU then passed a Franco-German compromise to allow self-declared terminal dues of up to 70% of the domestic postage rate, phasing them in from 2021 to 2025. However, countries receiving more than 75,000 metric tons of letter mail could move to self-declared rates on 1 July 2020. Trump adviser Peter Navarro declared that the agreement "more than achieved the President's goal," and UPU Director Siva Somasundram called it "a landmark decision for multilateralism and the Union."[25][26]

Standards

Standards are important prerequisites for effective postal operations and for interconnecting the global network. The UPU's Standards Board develops and maintains a growing number of international standards to improve the exchange of postal-related information between postal operators. It also promotes the compatibility of UPU and international postal initiatives. The organization works closely with postal handling organizations, customers, suppliers and other partners, including various international organizations. The Standards Board ensures that coherent regulations are developed in areas such as electronic data interchange (EDI), mail encoding, postal forms and meters. UPU standards are drafted in accordance with the rules given in Part V of the "General information on UPU Standards"[27] and are published by the UPU International Bureau in accordance with Part VII of that publication.

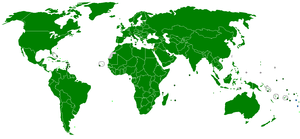

Member countries

All United Nations member states are allowed to become members of the UPU. A non-member state of the United Nations may also become a member if two-thirds of the UPU member countries approve its request. The UPU currently has 192 members (190 states and two joint memberships of dependent territories groups).

Member states of the UPU are the Vatican City and every UN member except Andorra, Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau. These four states have their mail delivered through another UPU member (France and Spain for Andorra, and the United States for the Compact of Free Association states).[28] The overseas constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten) are represented as a single UPU member, as are the entire British overseas territories. These members were originally listed separately as "Colonies, Protectorates, etc." in the Universal Postal Convention[29] and they were grandfathered in when membership was restricted to sovereign states.[30]

Observers

Palestine is an observer state in the UN, and it was granted special observer status to the UPU in 1999. In 2008 Israel agreed for Palestine's mail to be routed through Jordan,[31][32] although this had not been implemented as of November 2012.[33] Palestine began receiving direct mail in 2016.[34] In November 2018, Palestine signed papers of accession to the UPU.[35] However, its bid for membership was defeated in September 2019 by a vote of 56-23-7, with 106 countries not voting, which fell short of the required two-third majority of the UPU membership.[36]

States with limited recognition

States with limited recognition must route their mail through third parties, since the UPU does not allow direct deliveries.[37]

| State | Mail routed via |

|---|---|

| Abkhazia | Russia |

| Kosovo | Serbia |

| Nagorno-Karabakh | Armenia |

| Northern Cyprus | Turkey |

| Sahrawi Republic | Algeria |

| South Ossetia | Russia |

| Taiwan (Republic of China) | United States, Japan |

| Transnistria | Moldova |

Congresses

The Universal Postal Congress is the most important body of the UPU. The main purpose of the quadrennial Congress is to examine proposals to amend the Acts of the UPU, including the UPU Constitution, General Regulations, Convention and Postal Payment Services Agreement. The Congress also serves as a forum for participating member countries to discuss a broad range of issues impacting international postal services, such as market trends, regulation and other strategic issues. The first UPU Congress was held in Bern, Switzerland in 1874. Delegates from 22 countries participated. UPU Congresses are held every four years and delegates often receive special philatelic albums produced by member countries covering the period since the previous Congress.[38]

Philatelic activities

The Universal Postal Union, in conjunction with the World Association for the Development of Philately, developed the WADP Numbering System (WNS). It was launched on 1 January 2002. The website[39] displays entries for 160 countries and issuing postal entities, with over 25,000 stamps registered since 2002. Many of them have images, which generally remain copyrighted by the issuing country, but the UPU and WADP permit them to be downloaded.

Electronic telecommunication

In some countries, telegraph and later telephones came under the same government department as the postal system. Similarly there was an International Telegraph Bureau, based in Bern, akin to the UPU.[40] The International Telecommunication Union currently facilitates international electronic communication.

In order to integrate postal services and the Internet, the UPU sponsors .post.[41][42] Developing their own standards, the UPU expects to unveil a whole new range of international digital postal services, including e-post. They have appointed a body, the .post group (DPG) to oversee the development of that platform.[43]

Notes

- The Austrian and Hungarian delegates signed separately, but the preamble to the treaty considered Austria-Hungary to be a single country.

References

- "Universal Postal Union - United Nations System Chief Executives Board for Coordination". www.unsceb.org. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- "The UPU". Universal Postal Union website. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- A postage stamp honoring the sculptor and the monument was issued jointly by Switzerland and France.

- Beam, Christopher (5 January 2007). "How international mail works". Slate Magazine.

- Washburne, E. B. (1887). Recollections of a Minister to France, Volume I. New York: Scribner.

- Washburne, E. B. (1887). Recollections of a Minister to France, Volume II. New York: Scribner.

- "History". Universal Postal Union. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Krueger, Karl K. (January 1938). "By Post to Peace". The Rotarian. 52 (1): 38–39.

- Willoughby, Martin (1992). A History of Postcards. London England: Bracken Books. p. 31. ISBN 1858911621.

- "Languages". Universal Postal Union. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- King, Beverly; Johl, Max (1937). The United States Postage Stamps of the Twentieth Century, Volume I. H. L. Lindquist., p. 104

- "1898 Universal Postal Union Colors #279-284". Kenmore Stamp Company. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- "About UN Specialized Agency". Universal Postal Union. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- Adams, Cecil (12 December 1990). "Why Does the US Deliver Foreign Mail When We Don't Get Any Money for the Stamps?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- Morris, David Z. (14 June 2017). "The International Postal System Is Profoundly Broken -- And Nobody is Paying Attention". Pacific Standard.

- Campbell Jr., James I (9 April 2019). A Brief Overview of the History of the UPU Terminal Dues System (PDF). UPU Remuneration Systems - New Frontiers for an Old World?. Bern, Switzerland.

- "The Postal Illuminati". Planet Money (857). National Public Radio. 1 August 2018.

- "Member countries adopt new terminal dues system". news.upu.int. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- United States Government Accountability Office (October 2017). "GAO-18-112, Information on Changes and Alternatives to the Terminal Dues System" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- "Pexit? US prepares to pull out of Universal Postal Union". Deutsche Welle. 24 September 2019.

- "Universal Postal Union Reviews Three Options for Remuneration". Steiner Associates, LLC. E-Commerce Bytes. 10 April 2019.

- "Frequently Asked Questions: Third Extraordinary Congress". Universal Postal Union. 25 September 2019.

- "World Postal Union Rejects Trump's Favored Reform Plan". Associated Press. 24 September 2019.

- "UPU member countries narrow options on remuneration rates by rejecting Option B". Universal Postal Union. 24 September 2019.

- Solomon, Mark (20 September 2019). "Proposal floated to allow USPS self-declaration of foreign postal shipments; keep US in UPU". FreightWaves.

- "UPU member countries reach unanimous agreement on postal remuneration rates". Universal Postal Union. 25 September 2019.

- "UPU Postal Standardization Activities" (PDF). UPU. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- Gough, JP (6 October 2005). "The Evolution of the Postal Service in the Era of the UPU". Web Mavin. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "Universal Postal Convention". Universal Postal Union. 11 July 1952. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- "Constitution of the Universal Postal Union". Universal Postal Union. 10 July 1964. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- "Palestinian parcel post gets a boost". Universal Postal Union (UPU). Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "Israel and Palestinians to boost postal services with help from UN agency". Un.org. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- New resolution adopted on Palestinian postal operations | UPU Archived April 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. News.upu.int (2012-03-22). Retrieved on 2014-04-28.

- https://www.jpost.com/Arab-Israeli-Conflict/Palestinians-to-receive-direct-mail-for-the-first-time-466872

- RASGON, Adam (18 November 2018). "Times of Israel". Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "UN rejects Palestinian Authority request to join the Universal Postal Union". The National. 16 September 2019.

- "Members of the Universal Postal Union and Their Join Dates" (PDF). United Postal Stationery Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2017.

- "The Universal Postal Union (UPU)". Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations. Encyclopedia. 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- "WNS". www.wnsstamps.post. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- "THE CABLE QUESTION". The Brisbane Courier. National Library of Australia. 15 February 1900. p. 5. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- "About .post". Universal Postal Union. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- "IANA — .post Domain Delegation Data". Iana.org. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Gustavo Damy (19 September 2014). "Expression of Interest" (PDF). Universal Postal Union. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

Sources

- Codding, G. A. (1964). The Universal Postal Union: Coordinator of the International Mails. New York: New York University Press.

- "General Postal Union; October 9, 1874". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. The Lillian Goldman Law Library in Memory of Sol Goldman. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Universal Postal Union. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |