Tzvi Hersh Bonhart

Rabbi Tzvi Hersh Bonhart (Yiddish: רבי צבי הירש באנהאַרד; c. 1747 – c. 1810) later known as the Maggid of Vodislav was an 18th-century German Jewish preacher and intellectual, who is also the father of Simcha Bunim of Peshischa.

Tzvi Hersh Bonhart | |

|---|---|

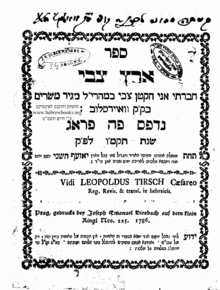

Title page of Eretz Tzvi | |

| Title | The Maggid of Vodislav |

| Personal | |

| Born | Tzvi Hersh Bonhart c. 1747 |

| Died | c. 1810 |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Nationality | German |

| Spouse | Sarah Rachel Sirkin |

| Children | Simcha Bunim of Peshischa |

| Parents |

|

| Main work | Eretz Tzvi |

| Dynasty | Peshischa |

Biography

Born around 1747 in Saxony, Germany, his father Rabbi Judah Leib Bonhart was a wealthy merchant and minor Rabbi in Saxony. In his early year's, Tzvi Hersh studied Medieval Jewish Philosophy, which he often references in his later works, quoting Ben Sira, Maimonides, Nahmanides and Ibn Ezra. He later moved to Vodislav, Poland, where he married Sarah Rachel Sirkin, the daughter of Betzalel HaLevi of Zhovkva. It was also during this time, that began to give sermons all over Lesser Poland, in which he promoted the juxtaposing of enlightenment rationalism with traditional Judaism, a belief which later defined the Peshischa movement. In 1784, he published his first work titled "Asara L'me'a" (lit. 'Ten to One Hundred') in Warsaw, which received minimal acclaim. However, in 1786, he published his magnum opus titled "Eretz Tzvi" (lit. 'The Land of Tzvi'), which was an extensive collection of all the sermons he had given. The work was widely received, even getting the approbation from Rabbi Yechezkel Landau. [1] Following his son's marriage, both he and his son began to develop an interest in Hassidic Judaism. In his old age, Tzvi Hersh still continued to travel to the several Hassidic communities across Poland. On one of these trips he met with Yisroel Hopstein and asked him to give him a blessing. Rabbi Hopstein replied stating that "You don't need my blessings, you have a son who will rescue you from wherever you are, even from the depths of hell!"[2] One of Tzvi Hersh's more famous teachings was in regards to how to keep the passion present in marriages. Tzvi Hersh replied stating that:[3]

"If a man makes a vow he will certainly not break his word, but merely keeping his word is not enough. He is commanded: ‘He must carry out all that has crossed his lips’—that he must fulfill the vow with same fervor as at the time that he took the vow. In most cases, when a person makes a vow he do so in a flush of enthusiasm, whereas the fulfillment of that vow is done without passion, as if he is forced to do so. The Torah therefore stresses: ‘You shall do—as you vowed."

Tzvi Hersh later died around 1810 in Vodislav.

See also

- Asara L'me'a (עשרה למאה) - Torah database.

- Eretz Tzvi (ארץ צבי) - Torah database.

References

- Rosen, Michael, 1945-2008 (2008). "A Biographical Sketch of R. Simhah Bunim". The quest for authenticity : the thought of Reb Simhah Bunim. Urim Publications. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-965-524-003-0. OCLC 837205625.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Heichal HaNegina: Tidbits from the Rebbe Reb Simcha Bunim of Pshischa". heichalhanegina.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- Moskowitz, Rabbi Steven. "Mattot". Retrieved 2020-06-17.