Tyrosine phosphorylation

Tyrosine phosphorylation is the addition of a phosphate (PO43−) group to the amino acid tyrosine on a protein. It is one of the main types of protein phosphorylation. This transfer is made possible through enzymes called tyrosine kinases. Tyrosine phosphorylation is a key step in signal transduction and the regulation of enzymatic activity.

History

In the summer of 1979, studies of polyomavirus middle T and v-Src associated kinase activities led to the discovery of tyrosine phosphorylation as a new type of protein modification.[1] Following the 1979 discovery that Src is a tyrosine kinase, the number of known distinct tyrosine kinases grew rapidly, accelerated by the advent of rapid DNA sequencing technology and PCR.[2] About one year later, researchers discovered an important role for tyrosine phosphorylation in growth factor signaling and proliferation, and by extension in oncogenesis through hijacking of growth factor tyrosine phosphorylation signaling pathways.

In 1990 receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) initiation of intracellular signaling was detected. Phosphotyrosine (P.Tyr) residues on activated RTKs are recognized by a phosphodependent-binding domain, the SH2 domain. The recruitment of SH2 domain proteins to autophosphorylated RTKs at the plasma membrane is essential for initiating and propagating downstream signaling. SH2 domain proteins may have a variety of functions, including adaptor proteins to recruit other signaling proteins, enzymes that act on membrane molecules, such as phospholipases, cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases that relay signals, E3 ubiquitin ligases, and transcription factors.[3] In 1995 proteins were found containing a second type of P.Tyr-binding domain, PTB, in RTK signaling. Gradually the number of identified tyrosine kinases and receptor tyrosine kinases grew. As of 2002, of the 90 known human tyrosine kinases, 58 were RTKs, and opposing the action of the tyrosine kinases were 108 protein phosphatases that can remove phosphate from P.Tyr in proteins.[4]

Signal transduction

Ushiro and Cohen (1980) discovered the important role of the phosphorylation of tyrosine as a regulator of intracellular processes and revealed changes in the tyrosine kinase activity of proteins in mammalian cells. Subsequently, the change in protein tyrosine kinase activity was shown to underlie the Ras-MAPK signaling pathway regulated by mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases.[5]

The classical scheme of transmission of the proliferative signals through the pathway mediated by growth factors (Ras-MAPK pathway) includes:

- association of growth factor with receptor

- dimerization of receptor and autophosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)

- module coupling of RTK with adaptor SH2−domain proteins; activation of Ras

- phosphorylation and activation of MAP kinases

- transmission of signal into genome.

Another pathway of transmission of proliferative signals into the genome, with participation of growth factors and tyrosine kinases, is the monocascade STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) protein pathway activated by receptors of growth factors and cytokines. The essence of this transmission consists in direct activation by tyrosine kinases of the STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) proteins located in the cytoplasm. This transmission is also provided by the SH2−domain contacts responsible for the coupling of phosphotyrosine-containing proteins.[6]

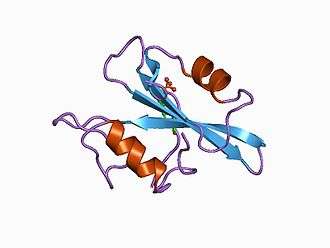

PTK

Two important classes of tyrosine kinase in tyrosine phosphorylation are receptor tyrosine kinase and nonreceptor tyrosine kinase. Receptor tyrosine kinases are type I transmembrane proteins possessing an N-terminal extracellular domain, which can bind activating ligands, a single transmembrane domain, and a C-terminal cytoplasmic domain that includes the catalytic domain. Nonreceptor tyrosine kinases lack a transmembrane domain. Most are soluble intracellular proteins, but a subset associate with membranes via a membrane-targeting posttranslational modification, such as an N-terminal myristoyl group, and can act as the catalytic subunit for receptors that lack their own catalytic domain.[7]

Reaction

Protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) catalyze the transfer of the γ-phosphate group from ATP to the hydroxyl group of tyrosine residues, whereas protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) remove the phosphate group from phosphotyrosine.[8]

Function

Growth factor signaling

Tyrosine phosphorylation of certain target proteins is required for ligand stimulation of their enzymatic activity. In response to EGF, PDGF, or FGF receptor activation, the SH2 domains of PLCγ bind to specific phosphotyrosines in the C-terminal tails of these receptors. Binding of PLCγ to the activated receptor facilitates its efficient tyrosine phosphorylation by the RTK. PDGF-induced activation of phospholipase C activity is abrogated in cells expressing PLCγ mutated in the tyrosine phosphorylation sites.[9]

Cell adhesion, spreading, migration and shape

Phosphorylation on tyrosine residues, which are localized on membrane proteins, stimulates a cascade of signaling pathways that control cell proliferation, migration, and adhesion. These tyrosine residues are phosphorylated very early. For example, p140Cap (Cas-associated protein) are phosphorylated within 15 minutes of cell adhesion to integrin ligands.[10]

Cell differentiation in development

Tyrosine phosphorylation mediates in signal transduction pathways during germ cell development and determines their association with the differentiation of a functional gamete. Until testicular germ cells differentiate into spermatozoa, cAMP-induced tyrosine phosphorylation is not detectable. Entry of these cells into the epididymis is accompanied by sudden activation of the tyrosine phosphorylation pathway, initially in the principal piece of the cell and subsequently in the midpiece.[11]

Cell cycle control

Transitions in the phases of the cell cycle are also dependent on tyrosine phosphorylation. In the late G2 phase, it is present as an inactive complex of tyrosine-phosphorylated p34cdc2 and unphosphorylated cyclin Bcdc13. In M phase, its activation as an active MPF displaying histone H1 kinase (H1K) originates from the concomitant tyrosine dephosphorylation of the p34cdc2 subunit and the phosphorylation of the cylin Bcdc13 subunit. As cells leave the S phase and enter the G2 phase, a massive tyrosine phosphorylation of p34cdc2 occurs.[12]

Gene regulation and transcription

Regulation with tyrosine phosphorylation plays a very important role in gene regulation. Tyrosine phosphorylation can influence the formation of different transcription factors and the subsequent development of their product. One of these cases is tyrosine phosphorylation of caveolin 2 (Cav-2) that negatively regulates the anti-proliferative function of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) in endothelial cells. Only tyrosine phosphorylation is essential for the negative regulation of anti-proliferative function and signaling of TGF-β in ECs.[13]

Endocytosis and exocytosis

The phosphorylation of tyrosine residues plays an important role in these two very important processes. Ligand-dependent endocytosis, which is not coupled to secretion, is known to be regulated via tyrosine phosphorylation. The effect of tyrosine phosphorylation is specific to rapid endocytosis. Dynamin is tyrosine phosphorylated in rapid endocytosis as well as in ligand dependent endocytosis.[14]

Insulin stimulation of glucose uptake

Insulin binds to the insulin receptor at the cell surface and activates its tyrosine kinase activity, leading to autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of several receptor substrates. Phosphorylation of selected tyrosine sites on receptor substrates is known to activate different pathways leading to increased glucose uptake, lipogenesis, and glycogen and protein synthesis, as well as to the stimulation of cell growth. In addition to the activation of these pathways by tyrosine phosphorylation, several mechanisms of downregulating the response to insulin stimulation have also been identified.[15]

Angiogenesis (formation of new blood vessels)

Protein tyrosine phosphorylation of capillary endothelial cells plays an important role in their proliferation. This phosphorylation can form new blood vessels.[16]

Regulation of ion channels in nerve transmission

Many studies demonstrating high levels of protein-tyrosine kinases and phosphatases in the central nervous system have suggested that tyrosine phosphorylation is also involved in the regulation of neuronal processes. High levels of protein-tyrosine kinases and phosphatases and their substrates at synapses, both presynaptically and postsynaptically, suggest that tyrosine phosphorylation may regulate synaptic transmission. The role of tyrosine phosphorylation in the regulation of ligand-gated ion channels in the central nervous system has been less clear. The major excitatory neurotransmitter receptors in the central nervous system are the glutamate receptors. These receptors can be divided into three major classes, AMPA, kainate, and NMDA receptors, based on their selective agonists and on their physiological properties. Recent studies have provided evidence that NMDA receptors are regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation.[17]

Tyrosine kinase and diseases

Tyrosine kinases are critical mediators of intracellular signaling and of intracellular responses to extracellular signaling. Changes in tyrosine kinase activity are implicated in numerous human diseases, including cancers, diabetes, and pathogen infectivity. Understanding the mechanism of CD4-mediated negative signaling is of particular interest in view of the progressive depletion of the CD4+ subset of T lymphocytes by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS. T-cells from HIV-infected individuals also display activation defects, and undergo spontaneous apoptosis in culture. Similarities between the inhibitory effects of anti-CD4 antibodies and HIV-derived gp 120 immune complexes on T-cells suggest that sequestration of this and/or other putative substrates by gp 120-mediated CD4 ligation in HIV-infected individuals may play a role in the loss of CD4+ cells and the inhibition of their activation.

See also

References

- Eckhart W, Hutchinson MA, Hunter T (1979). "An activity phosphorylating tyrosine in polyoma T antigen immunoprecipitates". Cell. 18 (4): 925–33. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(79)90205-8. PMID 229973.

- Hunter T, Eckhart W (2004). "The discovery of tyrosine phosphorylation: it's all in the buffer!". Cell. 116 (2 Suppl): S35–9, 1 p following S48. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00049-2. PMID 15055579.

- Pawson T (2004). "Specificity in signal transduction: from phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions to complex cellular systems". Cell. 116 (2): 191–203. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01077-8. PMID 14744431.

- Alonso A, Sasin J, Bottini N, Friedberg I, Friedberg I, Osterman A, et al. (2004). "Protein tyrosine phosphatases in the human genome". Cell. 117 (6): 699–711. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.018. PMID 15186772.

- Hunter T, Cooper JA (1985). "Protein-tyrosine kinases". Annu Rev Biochem. 54: 897–930. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.004341. PMID 2992362.

- Darnell JE (1997). "STATs and gene regulation". Science. 277 (5332): 1630–5. doi:10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. PMID 9287210.

- Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S (2002). "The protein kinase complement of the human genome". Science. 298 (5600): 1912–34. doi:10.1126/science.1075762. PMID 12471243.

- Hunter T (1998). "The Croonian Lecture 1997. The phosphorylation of proteins on tyrosine: its role in cell growth and disease". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 353 (1368): 583–605. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0228. PMC 1692245. PMID 9602534.

- Pasantes-Morales H, Franco R (2002). "Influence of protein tyrosine kinases on cell volume change-induced taurine release". Cerebellum. 1 (2): 103–9. doi:10.1080/147342202753671231. PMID 12882359.

- Di Stefano P, Cabodi S, Boeri Erba E, Margaria V, Bergatto E, Giuffrida MG, et al. (2004). "P130Cas-associated protein (p140Cap) as a new tyrosine-phosphorylated protein involved in cell spreading". Mol Biol Cell. 15 (2): 787–800. doi:10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0689. PMC 329393. PMID 14657239.

- Lin M, Lee YH, Xu W, Baker MA, Aitken RJ (2006). "Ontogeny of tyrosine phosphorylation-signaling pathways during spermatogenesis and epididymal maturation in the mouse". Biol Reprod. 75 (4): 588–97. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.106.052712. PMID 16790687.

- Meijer L, Azzi L, Wang JY (1991). "Cyclin B targets p34cdc2 for tyrosine phosphorylation". EMBO J. 10 (6): 1545–54. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07674.x. PMC 452818. PMID 1709096.

- Abel B, Willoughby C, Jang S, Cooper L, Xie L, Vo-Ransdell C, et al. (2012). "N-terminal tyrosine phosphorylation of caveolin-2 negates anti-proliferative effect of transforming growth factor beta in endothelial cells". FEBS Lett. 586 (19): 3317–23. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2012.07.008. PMC 3586282. PMID 22819829.

- Nucifora PG, Fox AP (1999). "Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates rapid endocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells". J Neurosci. 19 (22): 9739–46. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-09739.1999. PMC 6782969. PMID 10559383.

- Schmelzle K, Kane S, Gridley S, Lienhard GE, White FM (2006). "Temporal dynamics of tyrosine phosphorylation in insulin signaling". Diabetes. 55 (8): 2171–9. doi:10.2337/db06-0148. PMID 16873679.

- Hayashi A, Popovich KS, Kim HC, de Juan E (1997). "Role of protein tyrosine phosphorylation in rat corneal neovascularization". Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 235 (7): 460–7. doi:10.1007/bf00947067. PMID 9248844.

- Lau LF, Huganir RL (1995). "Differential tyrosine phosphorylation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits". J Biol Chem. 270 (34): 20036–41. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.34.20036. PMID 7544350.