Typhoon Halola

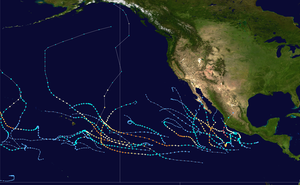

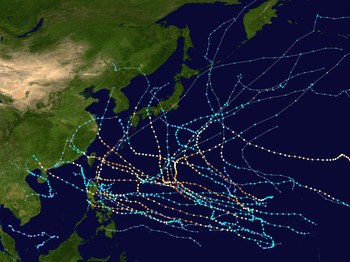

Typhoon Halola, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Goring, was a small but long-lived tropical cyclone in July 2015 that traveled 7,640 km (4,750 mi) across the Pacific Ocean. The fifth named storm of the 2015 Pacific hurricane season, Halola originated from a Western Pacific monsoon trough that had expanded into the Central Pacific by July 5. Over the next several days, the system waxed and waned due to changes in wind shear before organizing into a tropical depression on July 10 while well southwest of Hawaii. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Halola on the next day as it traveled westward. Halola crossed the International Date Line on July 13 and entered the Western Pacific, where it was immediately recognized as a severe tropical storm. The storm further strengthened into a typhoon over the next day before encountering strong wind shear on July 16, upon which it quickly weakened into a tropical depression as it passed south of Wake Island. However, the shear relaxed on July 19, allowing Halola to reintensify. On July 21, Halola regained typhoon status and later peaked with 10-minute sustained winds of 150 km/h (90 mph) and a minimum pressure of 955 hPa (mbar; 28.20 inHg). From July 23 onward, increasing wind shear and dry air caused Halola to weaken slowly. The system fell below typhoon intensity on July 25 as it began to recurve northwards. Halola made landfall over Kyushu on July 26 as a tropical storm and dissipated in the Tsushima Strait shortly after.

| Typhoon (JMA scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 2 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

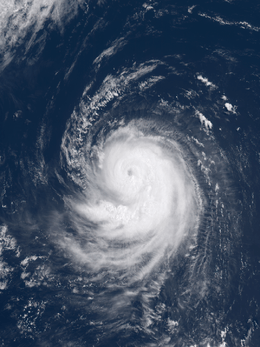

Typhoon Halola at peak intensity on July 22 | |

| Formed | July 10, 2015 |

| Dissipated | July 26, 2015 |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 150 km/h (90 mph) 1-minute sustained: 155 km/h (100 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 955 hPa (mbar); 28.2 inHg |

| Fatalities | None |

| Damage | $1.24 million (2015 USD) |

| Areas affected | Wake Island, Japan, South Korea |

| Part of the 2015 Pacific hurricane and typhoon seasons | |

The typhoon initially posed a significant threat to Wake Island, prompting the evacuation of all personnel from the military base spanning the atoll; however, no damage resulted from its passage. Heavy rains and strong winds buffeted the Ryukyu Islands, with record rainfall observed in Tokunoshima. Flooding and landslides forced the evacuation of several thousand people. Damage was relatively limited, though the sugarcane crop sustained ¥154 million (US$1.24 million) in damage. Two people were injured in Kyushu.

Meteorological history

Typhoon Halola's origins can be traced to a Western Pacific monsoon trough that spawned a weak low-level circulation on July 3. The trough expanded eastward into the Central Pacific by July 5, bringing the circulation with it. The trough would later cause the development of two more tropical cyclones in the Central Pacific: Ela and Iune. On July 6, the aforementioned circulation began to increase in organization. It then began to break away from the trough and drift northward on the next day as deep convection increased. Development temporarily halted late on July 7 after an upper-level anticyclone traveled northward, away from the center, causing easterly wind shear to affect the system. Late on July 9, all that remained was a swirl of clouds. The shear then relaxed and allowed the exposed low-level circulation to be covered by deep convection. The system continued to organize, developing into a tropical depression on July 10 at 06:00 UTC, while located approximately 1,650 km (1,025 mi) southwest of Honolulu, Hawaii. Slow strengthening continued over the next couple of days, with the nascent depression being upgraded to Tropical Storm Halola by the Central Pacific Hurricane Center at 00:00 UTC on July 11. A ridge to the north of the storm steered it generally westwards, though the weakening of this ridge on July 12 by an upper-level trough allowed Halola's motion to gain a northward component. The trough also inflicted slight northwesterly shear over Halola, causing Halola's 1-minute sustained winds to level off at 95 km/h (60 mph).[1] On July 13 at 00:00 UTC, Halola crossed the International Date Line and entered the Western Pacific,[1] falling under the purview of the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), which immediately recognized it as a severe tropical storm.[2]

Once in the Western Pacific, Halola began to intensify quickly, developing a small 15 km (9 mi) wide eye and good outflow channels.[3] As a result, the JMA assessed Halola to have strengthened into a typhoon at 00:00 UTC on July 14. Although the eye feature quickly disappeared, convection continued to deepen and Halola reached its initial peak intensity at 06:00 UTC with 10-minute sustained winds of 130 km/h (80 mph).[4][2] The US-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) simultaneously judged Halola to have 1-minute sustained winds of 155 km/h (100 mph), equivalent to Category 2 on the Saffir–Simpson scale.[5] Soon after, an increase in wind shear and a decrease in outflow led to a weakening trend.[6] The system fell below typhoon status at 06:00 UTC on July 15 as it approached Wake Island.[2] Convection became sheared to the east of the low-level circulation center as Halola passed south of Wake Island on July 16, reflecting the disorganized state of the system.[7] Amid the unfavorable upper-level environment, Halola weakened into a tropical depression on July 17, a status it would retain for the next two days.[2] As the system tracked steadily westwards under the influence of a strong ridge, it was met with dry air that further limited thunderstorm activity through July 18.[8]

On July 19, the environment surrounding Halola began to improve. Wind shear decreased and the storm moved west-northwestwards into an area of moister air.[9] As a result, the system began to consolidate once again, reintensifying to a tropical storm at 18:00 UTC.[2] An eye feature became visible on microwave satellite imagery as Halola passed over waters with surface temperatures near 30 °C (86 °F).[10] Quick strengthening followed, with the system reaching severe tropical storm status at 06:00 UTC on July 20 and typhoon status 18 hours later.[2] The eye contracted to a diameter of 9 km (6 mi) as the storm strengthened,[11] eventually reaching peak intensity at 18:00 UTC on July 21 with 10-minute sustained winds of 150 km/h (90 mph) and a minimum pressure of 955 hPa (mbar; 28.20 inHg).[2] Over the next 12 hours, Halola weakened slightly as its eye collapsed and reformed.[12][13] Halola remained a well-organized and compact system through July 22 despite worsening outflow,[14] with the JTWC assessing that it had once again attained 1-minute sustained winds of 155 km/h (100 mph) at 12:00 UTC.[5]

On July 23, Halola began to weaken gradually as wind shear increased once again and dry air began to impinge on the system.[2][15] The typhoon entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) just before 08:00 UTC and PAGASA assigned it the local name Goring;[16] the storm remained northeast of the Philippines and exited the PAR the next day.[17] Dry air completely encircled the circulation by the end of July 24, causing Halola's convection to slowly dissipate. The system weakened below typhoon status on July 25 as it began to curve northwards.[18][2] During this time, Halola crossed over the Ryukyu Islands, passing just northeast of Okinawa Island and landing a direct hit on the Amami Islands.[19] On July 26, Halola made landfall as a tropical storm over Saikai, Nagasaki at 09:30 UTC and Sasebo, Nagasaki at 10:00 UTC.[2][20][21] Land interaction quickly took its toll on the cyclone,[22] and Halola was last noted by the JMA a couple hours later as it dissipated just north of Kyushu.[2] This ended Halola's 16-day, 7,640 km (4,750 mi) long track across the Pacific Ocean.[19]

Impact

Wake Island

Typhoon Halola was the first significant threat to Wake Island since Hurricane Ioke in 2006, which caused tremendous damage and forced the closure of the island for three months. The Tropical Cyclone Condition of Readiness (TCCOR) level was raised to 3—indicating winds of 93 km/h (58 mph) or higher were possible within 48 hours—by 2:00 p.m. local time on July 14.[23] That day, a Boeing C-17 Globemaster III aircraft from the Hawaii Air National Guard was used to evacuate 125 Department of Defense personnel deployed on Wake Island due to the threat of storm surge. The evacuees were brought to Anderson Air Force Base on Guam.[24][25] The TCCOR was raised to level 2—indicating winds of 93 km/h (58 mph) or higher were expected within 48 hours—on July 15. Warnings were discontinued as the storm weakened and moved away from the island the following day.[23]

Members of the 36th Contingency Response Group and the 353d Special Operations Group were parachuted onto the island on July 18 to conduct damage assessments and clear the airfield of debris.[26] Little, if any, damage was incurred according to their assessments.[27] The airfield was re-opened on July 20 and personnel resumed normal operations.[26]

Japan and South Korea

On July 22, Sasebo Naval Base was placed on alert for possible effects from the approaching typhoon. TCCOR 3 was raised for all United States military bases in Okinawa the next morning. This was subsequently extended on July 24 to cover Sasebo and Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni while the bases on Okinawa were placed under TCCOR 2. Additionally, TCCOR 4—indicating winds of 93 km/h (58 mph) were possible within 72 hours—was raised for Camp Walker and Chinhae Naval Base in South Korea. During the evening of July 24, TCCOR 1—indicating winds of 93 km/h (58 mph) were expected within 12 hours—was issued for the Okinawa bases. Sasebo Naval Base entered TCCOR 1 late on July 25. Following the storm's degradation into a depression on July 26, all TCCOR levels were dropped or reduced.[23] More than 100 flights to and from Naha Airport were cancelled, affecting approximately 16,000 passengers, with All Nippon Airways comprising the majority of affected flights.[23] Eight flights to and from Kumejima were also canceled.[28] 23 highway bus services by 16 operators were suspended.[29] The JMA warned residents across Kyushu to be on alert for flooding.[30]

Owing to the typhoon's northward turn, Okinawa was largely spared. Sustained winds at Kadena Air Base reached 48 km/h (30 mph), with gusts reaching 69 km/h (43 mph).[23] East of Okinawa in the Daitō Islands, sustained winds reached 114 km/h (71 mph) on Minamidaitōjima with a gust of 157 km/h (98 mph); both values were the highest in relation to the storm on land. Similar winds were recorded on Amami Ōshima, situated between Okinawa and Kyushu. Torrential rains affected portions of the archipelago, with Isen, Tokunoshima, receiving record-breaking accumulations. Twenty-four-hour totals reached 444 mm (17.5 in), including 114.5 mm (4.51 in) in one hour and 258.5 mm (10.18 in) in three hours; all three values were record amounts since the station began observations in 1977 and considered a 1-in-50 year event.[19][31] Rainfall reached 109 mm (4.3 in) on Okinoerabujima.[32] Ironically, Halola helped suppress rainfall across the majority of mainland Japan by severing a plume of moisture previously bringing several days of heavy rain. Most areas across western Japan received modest rainfall from the dissipating storm.[19]

Throughout the Daitō Islands, sugarcane farms were significantly affected by Typhoon Halola, resulting in ¥154 million (US$1.24 million) in damage.[33] The heavy rains on Tokunoshima prompted the evacuation of 7,500 residents and flooding damaged 90 homes.[19][34] Multiple landslides were reported on the island.[34] Power outages took place on Kitadaitōjima and Minamidaitō.[35] A landslide in Kunigami forced the closure of National Route 331.[36] In mainland Japan, one person was injured in Kumamoto Prefecture, Kyushu, after falling from a roof, while another person in Nagasaki hit their head after falling from a ladder.[37] In Akita Prefecture, Honshu, river levees along the Sainai River were breached by heavy rain brought on by the combination of a weather front and the remnants of Halola.[37][38] In response to the effects of Halola as well as Typhoon Nangka which struck Japan ten days earlier, the Cabinet of Japan activated additional financial support for affected areas through the Catastrophic Disasters Act.[37]

See also

References

- Derek Wroe (July 9, 2017). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Halola (PDF) (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- Typhoon Best Track 2015-08-25T01:00:00Z (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 16". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 14, 2015. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 17". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 14, 2015. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- J. H. Chu; A. Levine; S. Daida; D. Schiber; E. Fukada; C. R. Sampson. "Western North Pacific Ocean Best Track Data 2015". United States Naval Research Laboratory Marine Meteorology Division & Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 18". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 14, 2015. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 25". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 16, 2015. Archived from the original on July 16, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Depression 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 32". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 18, 2015. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Depression 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 38". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 19, 2015. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 41". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 46". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 21, 2015. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 47". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 21, 2015. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 48". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 22, 2015. Archived from the original on July 22, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 51". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 22, 2015. Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 53". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 23, 2015. Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "Severe Weather Bulletin #1 Tropical Cyclone Alert: Typhoon 'Goring'". Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration. July 23, 2015. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015.

- "Severe Weather Bulletin #5 Tropical Cyclone Alert: Typhoon 'Goring'". Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration. July 24, 2015. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015.

- "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 58". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 24, 2015. Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- Nick Wiltgen (July 27, 2015). "Typhoon Halola Reaches End of 17-Day Journey Through Pacific (Recap)". Atlanta, Georgia: The Weather Channel. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- "平成27年 台風第12号に関する情報 第94号" (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "平成27年 台風第12号に関する情報 第96号" (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on July 26, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- "Tropical Depression 01C (Halola) Warning Nr 066". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. July 26, 2015. Archived from the original on July 27, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- Dave Ornauer (July 25, 2015). "Pacific Storm Tracker: [Typhoon Halola]". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- "Total force effort ensures successful typhoon evacuation". Anderson Air Force Base, Guam: Pacific Air Forces. July 15, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- Senior Airman Orlando Corpuz (July 17, 2015). "Total force effort ensures successful typhoon evacuation". Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam, Hawaii: 154th Wing. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- "353rd SOG collaborates with 36th CRG to open Wake Island airfield". Wake Island: Defense Media Activity. Defense Video & Imagery Distribution System. July 20, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- Senior Airman Alexander W. Riedel (July 22, 2015). "Contingency response Airmen assist in Wake Island storm recovery". Wake Island: United States Air Force. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- "台風12号:久米島、鹿児島便など船の欠航8便". Okinawa Times (in Japanese). July 26, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- 平成28年台風12号による被害状況等について (PDF) (Report) (in Japanese). 内閣府. July 28, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "台風12号、熱帯低気圧に 長崎・佐世保に上陸後" (in Japanese). 朝日新聞. July 26, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- "台風12号 徳之島で「50年に1度」の記録的大雨 伊仙町で1時間に114ミリ" (in Japanese). 産経ニュース. July 25, 2015. Archived from the original on July 28, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- Kristina Pydynowski (July 27, 2015). "Halola Weakens, Bringing Rain to Japan". AccuWeather. Archived from the original on August 1, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- "台風12号、キビ被害1億5400万 南北大東". Ryūkyū Shimpō (in Japanese). July 28, 2015. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- "台風12号 徳之島町で浸水被害90棟". Yomiuri Shimbun (in Japanese). July 27, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- "大雨・暴風 大東と沖縄本島の生活に影響". Okinawa Times (in Japanese). July 26, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- "国頭林道2ヵ所、台風で土砂崩れ 東村国道、復旧進まず". Ryūkyū Shimpō (in Japanese). July 28, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- 平成27年台風第12号による大雨等に係る被害状況等について (PDF) (Report) (in Japanese). 内閣府. July 27, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- "県内大雨、斉内川の堤防決壊 JRダイヤも混乱". 秋田魁新報社 (in Japanese). July 25, 2015. Archived from the original on August 2, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Typhoon Halola. |

- JMA General Information of Typhoon Halola (1512) from Digital Typhoon

- 01C.HALOLA from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory