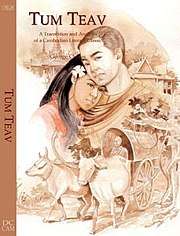

Tum Teav

Tum Teav (Khmer: ទុំទាវ) is a mid-19th century Cambodian romantic tragedy folk tale. It is originally based on a poem and is considered the "Cambodian Romeo and Juliet" and has been a compulsory part of the Cambodian secondary national curriculum since the 1950s.[1]

Although its first translation in French had been made by Étienne Aymonier already in 1880, Tum Teav was popularized abroad when writer George Chigas translated the 1915 literary version by the venerable Buddhist monk Preah Botumthera Som or Padumatthera Som, known also as Som, one of the best writers in the Khmer language.[2]

Plot

The tale relates the encounters of a musically talented, novice Buddhist monk named Tum and a beautiful adolescent girl named Teav. During his travels from Ba Phnum, Prey Veng province, to the province of Tbaung Khmum, where he has gone to sell bamboo rice containers for his pagoda, Tum falls in love with Teav, a very beautiful young lady who is drawn to his beautiful singing voice. She reciprocates his feelings and offers Tum some betel and a blanket as evidence of her affections; she prays to Buddha that the young monk will be with her for eternity. Upon returning to his home province, Tum is consumed with longing for Teav and soon returns to Tbaung Khmum. He initially spends some time in Teav's home despite her being 'in the shade' (a period of a few weeks when the daughter is supposedly secluded from males and taught how to behave virtuously). After professing their love for one another, Tum and Teav sleep together. Soon afterward, he is recruited by King Rama to sing at the royal palace, and he leaves Teav once again.

Teav's mother is unaware of her daughter's love for the young monk, and in the meantime she has agreed to marry her daughter off to the son of Archoun, the powerful governor of the province. Her plans are interrupted, however, when emissaries of Rama—equally impressed by Teav's beauty—insist that she marry the Cambodian king instead. Archoun agrees to cancel his son's wedding arrangement, and Teav is brought to the palace. When Tum sees that Teav is to marry the king, he boldly sings a song that professes his love for her. Rama overcomes his initial anger and agrees to allow the young couple to marry.

When Teav's mother learns of her daughter's marriage, she feigns illness as a ruse to lure Teav back to her village, whereupon she once again tries to coerce her into marrying Archon's son. Teav sends word to Tum of the impending wedding, and Tum arrives with an edict from the king to stop the ceremony. Tum gets drunk, announces he is Teav's husband and kisses her in public. Enraged, Archoun commands his guards to kill Tum, who is beaten to death under a Bo tree. Grief-stricken, Teav slits her own throat and collapses on Tum's body. When Rama hears of the murder, he descends upon Archoun's palace, ignores the governor's pleas for mercy, and orders Archoun's entire family—including seven generations worth of relatives—be taken to a field and buried to their necks. An iron plow and harrow are then used to decapitate them all.[3]

Origins

As with any oral tradition, pinning down the origins of the story is an elusive task. The story is believed to have originated in the 17th or 18th century and is set in Kampong Cham around a century earlier. However, in some versions the king in question is purported to be Reamea who reigned in the mid-17th century, coming to the throne through an act of regicide and subsequently converting to Islam.

Comparison with Romeo and Juliet

The tale has been compared to Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet but unlike the 'silver lining' conclusion of Romeo and Juliet, this story finishes with the king exacting rather extreme punishment – slaughtering every family member (including infants) remotely connected to the deception and the murder of Tum, making hereditary slaves of the entire village and exacting crippling extra taxes from a wider area in perpetuity.

Analysis and Adaptations

The story has been portrayed in many forms including oral, historical, literary, theater, and film adaptions.

Given that it plays such a central role in Cambodian culture, a wealth of different versions and including school plays have created distinctive interpretations of the tale. One of the most influential (and the one which serves as the basis for the version used in schools) sees the events through a rather crude interpretation of the Law of Karma, whereby Tum's death due to his impulsive decision to disrobe against the wishes of his abbot (who'd asked Tum to wait just a few weeks), and Teav's demise is attributed to her disobeying her mother's wishes.[4]

A later, more sophisticated, Buddhist interpretation focused on the way in which the protagonists' uncontrolled desires (principally Tum's lust and Teav's mother's desire for wealth and status) led to inevitable consequences. Another interpretation produced during King Norodom's reign linked the story's finale to Cambodia's history of excessive violence and subjugation of the poor. Norodom abolished slavery in the kingdom.

Whilst the lovers are unquestionably faithful and devoted to each other until the end, Teav is a victim of her mother's abuse of parental power. Her mother was in making pre-arranged marriage arrangements strongly motivated by greed, or fear of defying the governor. Tum's behavior on the contrary is powerfully ambivalent, and there is significant dexterity to his character. Many scholars interpret Tum Teav as a classic tale of the clash between social duty and romantic love. Every culture has its version of such a tension, yet modern Western society has all but forgotten the concept of obligation.[5]

A comic-strip version produced in Phnom Penh in 1988 explained to children that the young protagonists were tragic heroes who were destined to fail because their class struggle against feudalism was based on individual aspiration and not part of an ideologically-driven government-organised movement.

Critical scholarship using Tum Teav is diverse. Tum Teav was the exemplary text in a 1998 article, "A Head for an Eye: Revenge in the Cambodian Genocide,"[6] by Alexander Laban Hinton that tries to understand anthropological motivations for the scale of violence perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge. That article reads in Tum Teav a cultural model of karsângsoek, or "disproportionate revenge." Ârchoun's murder of Tum, a blow to the authority of the King, is returned by the genocide of Ârchoun's line: "a head for an eye." Another critical study was written in 1973 during the chaos of Lon Nol's rule and had contemporary events very much in mind.

In 2000, the music production company Rasmey Hang Meas adapted the story into a full-length karaoke musical on DVD.[4]

In 2003, the story was again adapted into a two-hour film directed by Fay Sam Ang.[7]

A 2005 book of Tum Teav, was released with a monograph containing the author's translation of the Venerable Botumthera Som's version. It also examines the controversy over the poem's authorship and its interpretation by literary scholars and performers in terms of Buddhism and traditional codes of conduct, abuse of power, and notions of justice.

See also

- Literature of Cambodia

- Tum Teav (2003 film)

References

- Tum Teav - Monument Books Archived 2007-12-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Documentation Center of Cambodia - Tum Teav: A Translation and Analysis of a Cambodian Literary Classic

- Our Books » Tum Teav Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Khmer440

- Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) Archived 2007-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Hinton, Alexander Laban (1998). "A Head for an Eye: Revenge in the Cambodian Genocide". American Ethnologist. 25 (3): 352–377. doi:10.1525/ae.1998.25.3.352. JSTOR 645789.

- http://seassi.wisc.edu/Activities/SEASSI%20Film%20Series%202005.pdf